By Faisal Irfani.

Arbaini thought he was being followed. He never reported it to the police because he didn’t want to succumb to fear, his friend Kisworo Cahyono says. But he had reason to be worried.

A farmer from Nateh in South Kalimantan, on the island of Borneo, Arbaini had over the past few years become a leading figure in a local movement opposed to a open-pit coal mine that was set to cut into the mountains near his home. He had been threatened before.

In December 2017, the mining company PT Mantimin Coal Mining (MCM) acquired a permit to exploit an area spanning more than 6,000 hectares, stretching across three districts—Tabalong, Balangan, and Hulu Sungai Tengah—and encompassing forests, residential areas, rice fields and rivers. It encroached on the Meratus Mountains, where — according to the environmental nonprofit Walhi South Kalimantan — 4,000 hectares had already been converted into open-pit mines.

Local tradition holds that the Meratus Mountains are the origin of humanity, and the ecosystem provides communities with the water they need for agriculture. Locals began a campaign, “Save Meratus,” to try to prevent further destruction in the area. Arbaini joined, and soon became an active member. He threw himself into campaigning, travelling to Jakarta, Indonesia’s capital city, to contest MCM’s mining permits at the Jakarta State Administrative Court. Arbaini’s commitment and leadership to the campaign led his neighbours to dub him Abah Nateh — elder of the village of Nateh.

“He was deeply disturbed by these mining activities because he did not want the coal mining presence to destroy everything,” said Kisworo, executive director at Walhi South Kalimantan, who worked with Arbaini on some of his earliest campaigns in 2018.

In 2019, Save Meratus’ legal campaigns succeeded in getting MCM’s permit annulled. The company applied for a judicial review. While the appeal was being considered, armed thugs twice visited Arbaini’s house. “The clear message they conveyed when they came was to stop opposing the presence of the mining company,” Kisworo says.

Finally, in February 2021, the judicial review was rejected, halting the mine’s advance. The Save Meratus Campaign continued, staging protests against companies they suspected of engaging in illegal mining.

But this July, Arbaini’s contacts at Walhi received tragic news. Their friend was dead. The official account of the incident alleges that the activist was stabbed by a neighbour who Arbaini had reprimanded for drunkenness. A suspect has been arrested and charged with assault. But Kiswoyo and his colleagues are left with significant doubts over what really happened.

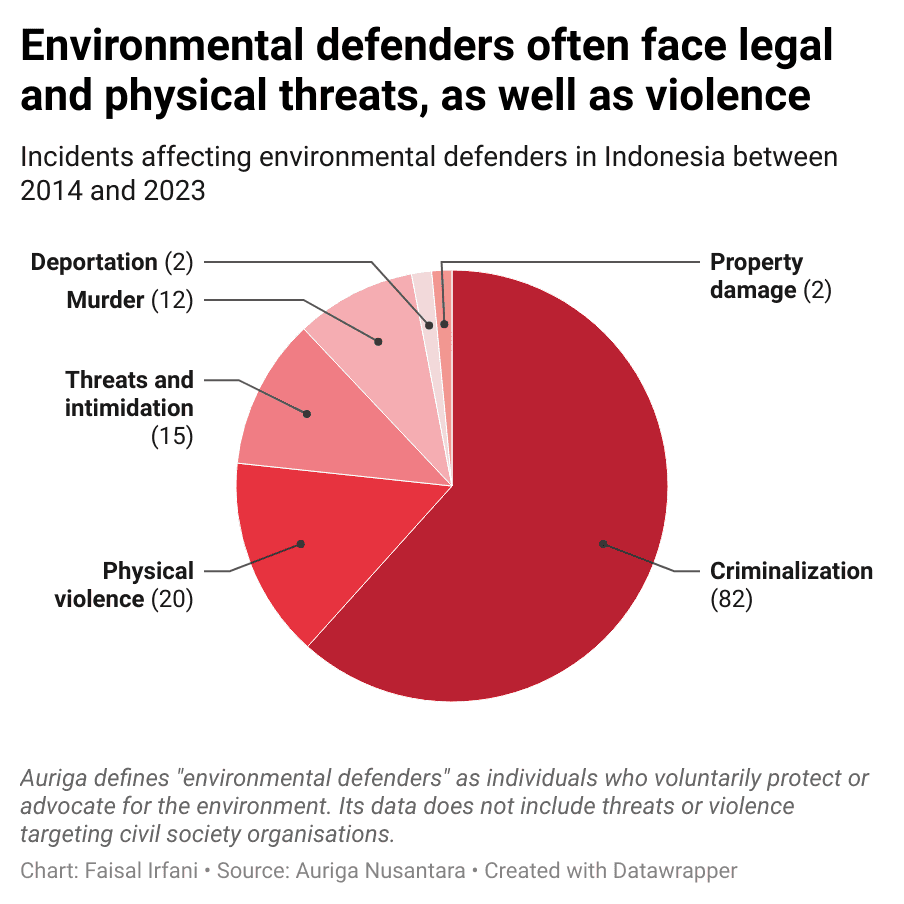

Arbaini’s death, they say, fits a pattern of attacks on environmental defenders in Indonesia. At least 12 activists working on environmental causes have been killed in Indonesia since 2018, according to data collected by the nonprofit Auriga Nusantara. In many cases, police don’t link incidents to the victims’ activism, and treat the crimes as “ordinary acts of violence,” says Roni Saputra, Auriga’s director of law enforcement.

“What actually happened and what motivated the murder remain unanswered by the authorities,�” Roni says. “The police stop at apprehending the perpetrator, but the deaths themselves often involve several irregularities. [The victims’] status as critical environmental defenders cannot be overlooked.”

Roni compared Arbaini’s death to that of Golfrid Siregar, a environmental defender and lawyer from Walhi’s North Sumatra branch, in 2019. Siregar was found unconscious on the Simpang Pos flyover in the regional capital of Medan in the early hours of the morning. After three days in intensive care at Adam Malik General Hospital, he died. The police gave the cause of death as “a single-vehicle traffic accident”—suggesting that he had crashed his motorbike. The official medical record stated that Golfrid died from head trauma, but Walhi claimed at the time that Golfrid appeared to have been struck with a blunt instrument, and that his body did not show the typical signs of a traffic accident.

At the time of his death, Golfrid was campaigning against a plan to build a hydroelectric power plant in the Batang Toru river area. Shortly after Golfrid’s death, North Sumatera Hydro Energy, the operator of the power plant, discouraged “speculation” over the alleged links between the company and Golfrid’s death on the grounds that it “could create insinuations that may violate the presumption of innocence”.

In 2021, Arman Damopolii, a farmer from North Sulawesi, was shot and killed by an unknown assailant while protesting against illegal gold mines that he claimed threatened the ecosystem in his village. His case remains unresolved. PT Bulawan Daya Lestari (DBL), the gold mining company that local communities were protesting against, stated to local media at the time that the incident did not take place within its concession. Police arrested a suspect in October 2021 but have not made additional details public since then. The Gecko Project was unable to reach DBL for comment.

Later that year, Jurkani, a lawyer from South Kalimantan who was campaigning against illegal coal mining in the Tanah Bambu region of South Kalimantan, was killed after his car was intercepted by a group of people suspected by the human rights watchdog Komnas HAM of being illegal coal miners. According to Komnas HAM, the lawyer was on his way to report the miners to the police when he was attacked and killed with a machete. The police said the killers were under the influence of alcohol, and official reports didn’t consider Jurkani’s advocacy as a motive.

While the deaths of activists make headlines, environmental defenders in Indonesia also routinely face other forms of violence and intimidation. Auriga has documented dozens of cases of physical threats and other forms of intimidation, including property damage, over the last decade.

“Criminalisation”—the use of the legal system to harass and intimidate activists—is also widespread. Activists can be arrested under a wide range of laws, from trespass to criminal defamation to provisions in the mining code. Most of the cases recorded by Auriga related to disputes over land use by the mining and energy sectors or the plantation industry, where powerful businesspeople often wield significant influence over local and national politics.

Indigenous communities often find themselves in the path of these industries. The indigenous rights advocacy group Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nusantara (AMAN) collates reports of conflict. In 2023, the group found that 204 people had suffered injuries from violence related to land disputes. One person was shot and killed. At least 100 indigenous peoples’ houses were destroyed, AMAN says.

“As time goes on, indigenous communities are increasingly marginalised by development policies. When they stand up for their rights, they are vulnerable to criminalization, violence, and imprisonment for defending what is a legacy of their ancestors—namely, their living space,” says Syamsul Alam Agus, chairman of the executive board of the Indonesian Indigenous Peoples Defenders Association (PPMAN), an affiliate of AMAN.

Conflicts over land—and attacks on environmental defenders—are likely to increase as the Indonesian government and companies push for more investment in mining and agriculture, according to Agung Wardana, an environmental law lecturer at Gadjah Mada University. Investment projects need stability, he says, and protests and legal disputes are inconveniently disruptive.

When peaceful attempts at bringing communities onside through corporate social responsibility fail, the state tends to intervene to instil “discipline,” Wardana says. “Discipline in this context takes the form of intimidation, direct violence such as kidnapping or even murder, as well as the use of existing legal systems through courts. The aim is to compel communities to align with the agendas of the government and corporations.”

There are provisions in Indonesian law that should protect the right of people to protest and advocate for the environment, Wardana says, but the police rarely seem to apply them. Instead, there is a widespread perception that law enforcement and the courts “tend to serve larger interests or agendas, including development or economic growth agendas.”

Two weeks ago, the Indonesian government issued a new regulation that states that environmental defenders cannot be prosecuted in criminal cases or sued in civil cases. The regulation also includes measures to protect environmental defenders from violence, such as setting up a communications channel for complaints and training law enforcement officers in environmental protection issues.

Andi Muttaqien, executive director of the environmental nonprofit Satya Bumi, welcomed the regulation but emphasised that legal loopholes remain that could allow environmental defenders to be threatened or criminalised.

In South Kalimantan, Arbaini’s friends want the investigation into his death to continue, even though a suspect has been arrested and charged.

“The most concerning issue is that we don’t know the background of the suspect. He had only been living in Nateh for two or three months, and no one seems to know who he is, where he came from, or why he came to Nateh,” Kiswoyo says.

The Gecko Project made multiple attempts to contact MCM by email and phone, but did not receive a response.

AKBP Pius X Febry Aceng Loda, head of the Hulu Sungai Tengah police, has denied that Arbaini’s death had any connection to mining issues. “The motive behind the murder of Arbaini (65), also known as Abah Nateh, was purely assault and had no connection to mining issues that had previously surfaced,” he says.

Whatever the circumstances of his death, Arbaini’s legacy will continue, Kiswoyo says. He remembers his friend as a generous man, who always insisted his guests left his home with full stomachs.

“He always insisted that we eat first. No one was allowed to leave his house hungry. That was a strict rule,” he says. “Even though my friends and I knew that the food at Arbaini’s home was only enough for his family and not for many guests, he always went out of his way to host us very well. He was always like that.”

The fight against the mines will continue too, he says. “I’ve learned from Arbaini that preserving nature is our duty. It can be exhausting and frightening at times. But after that, we rise again to continue the fight.”

Header image: Composite of a “Save Meratus” banner on the river in Nateh Village in October 2019 and photos of Arbaini. Graphic by Hendra Afrians; photos by WALHI Kalsel.