- A plantation project in Papua has destroyed thousands of hectares of rainforest and decimated the traditional food sources of indigenous peoples, an investigation by The Gecko Project found.

- The project ground to a halt in 2014 because it wasn’t financially viable. But it has since been revived by millions of dollars from two Indonesian government bodies whose mission is to support the country’s climate change commitments.

- The financing points to a clash between two pillars of the Indonesian government’s climate change strategy: protecting its rainforests, but also using less coal by burning increasing volumes of wood.

- Photos by Albertus Vembrianto.

Millions of dollars in green financing intended to help Indonesia reduce its carbon emissions have been invested in a project that is destroying rainforest in Papua, one of the world’s most biodiverse landscapes.

The money has been used to help an Indonesian conglomerate, Medco Group, construct a biomass power plant that is being fuelled by burning wood.

Medco has already cleared large tracts of rainforest, establishing timber plantations in its place. As a result of the financing, it plans to expand its plantations by at least 2,500 hectares and cut down more rainforest.

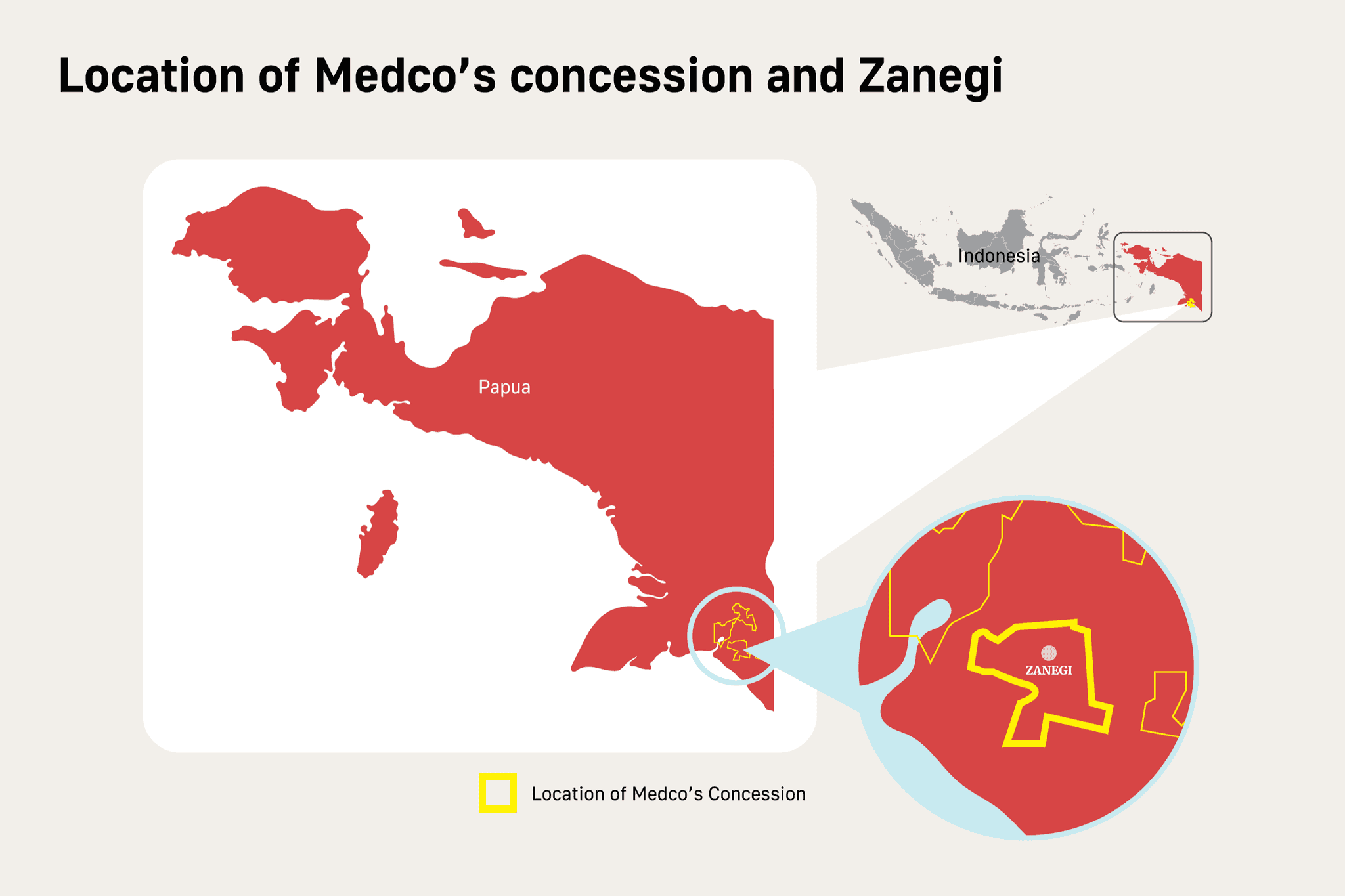

The project has targeted the ancestral territory of the Marind people, hunter-gatherers indigenous to the lowlands of Papua, in the far eastern reaches of Indonesia.

Medco’s operations have damaged the Marind’s traditional food sources, an investigation by The Gecko Project found. Deforestation has made it significantly harder for them to source game, according to multiple interviewees.

Some families living in the village of Zanegi, in the shadow of Medco’s plantation, now regularly consume meals consisting solely of rice. Records from 2022 show that a third of young children seen by health workers in Zanegi were suffering from impaired development because of a lack of access to nutritious food.

Almost $4.5 million in financing for the power plant came from a state-owned company, which claims the power plant is helping to deliver on Indonesia's climate change commitments by generating renewable energy. But the area licensed to Medco includes large areas of “primary”, or intact, swamps and rainforests: landscapes Indonesia has committed to protect in order to curtail its vast carbon footprint.

Medco received further financing from a government fund that has been used to channel international support to help Indonesia reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by protecting rainforests.

The Indonesian government’s backing for the project reflects a yawning inconsistency in its plans to tackle climate change. On the one hand, it has committed to protect its rainforests and peatlands, after decades of unrestrained deforestation and land fires made it one of the world’s largest sources of greenhouse gases.

On the other, it hopes to scale back its use of coal by burning increasing volumes of wood. Analysis by environmental activists indicates that vast new areas of timber plantations will be required to meet the demand that this creates. This could lead to rainforests being cut down to be replaced by fast-growing tree species.

“This is the reason we have opposed it from the beginning,” said Yuyun Indradi, director of Trend Asia, a nonprofit that monitors the government’s energy policies. “Indonesia’s biodiversity will be damaged by rapid development of monoculture tree plantations.”

Money from international donors has poured into Indonesia in recent years to help protect its forests and peatlands. In the past year alone, the UN Development Programme and Norwegian government have paid more than $100 million for that purpose into the Indonesian Environment Fund, or IEF – the same body that was used to finance Medco’s power plant in Papua.

In a stark illustration of the contradictions at the heart of Indonesia’s policies, that means the fund has been used to finance both forest conservation and a project predicated on deforestation.

In an interview, Endah Tri Kurniawaty, director of fund collection and development at the IEF, insisted that international climate funds would only be used in ways approved by its donors. Meanwhile the support for Medco, she said, had been approved by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry and was an appropriate use of its resources.

“It’s just the bones that we eat”

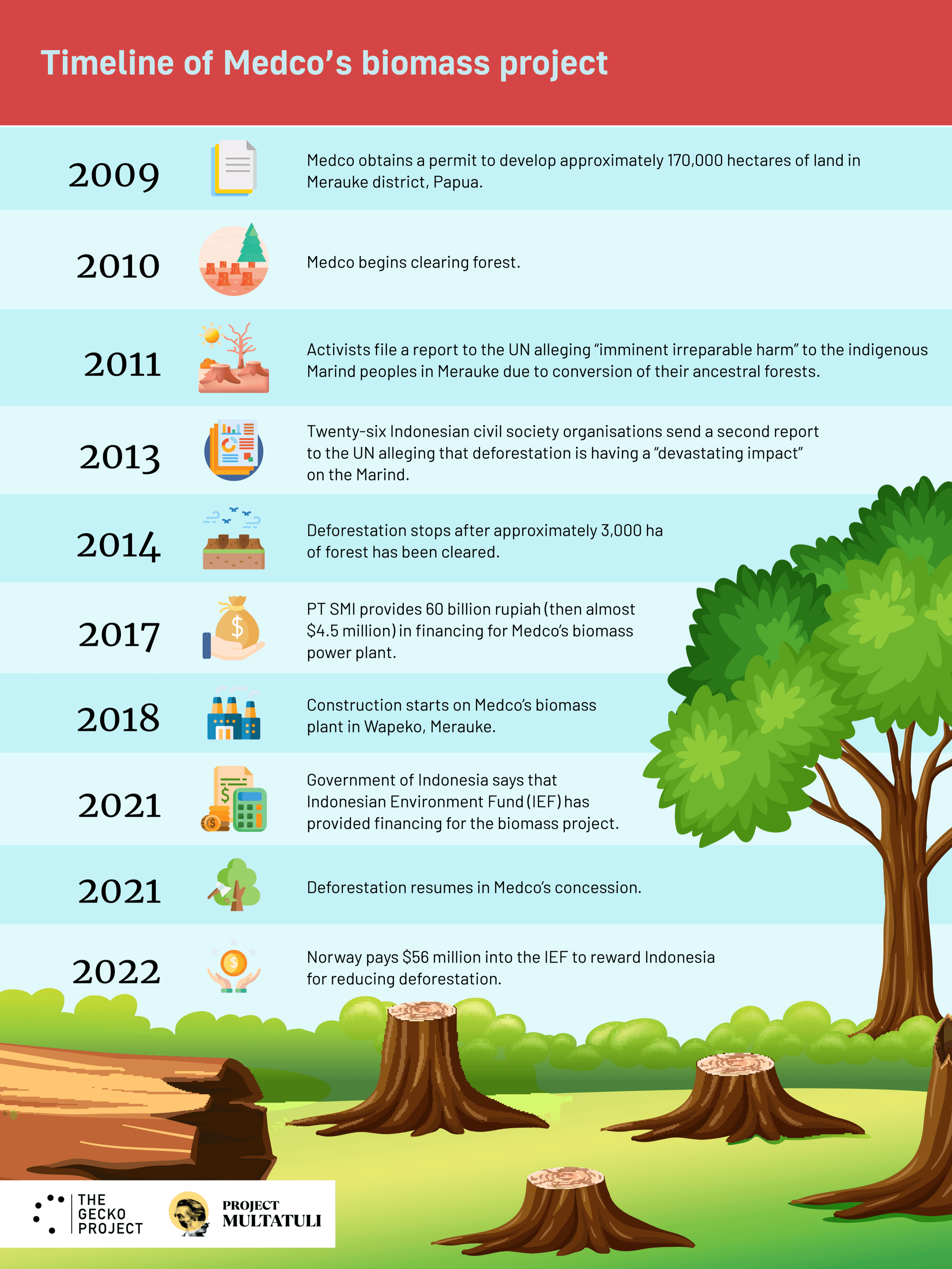

Medco’s project started life in the late 2000s, as part of a major Indonesian government programme to convert large portions of southern Papua into a source of food and energy. The company’s initial plan was to plant a vast timber plantation that would produce wood chips for export.

Medco obtained a licence for some 170,000 hectares of land, overlapping substantially with the ancestral territory of indigenous Marind people living in a village named Zanegi. The Marind source game, fish and sago – their staple foods – from the forests and swamps north of Zanegi.

The village lies at the heart of the TransFly region, a landscape once described by the World Wide Fund for Nature as “the environmental jewel of the Asia-Pacific region.” It is a mosaic of wetlands, savannas and forests that is home to hundreds of bird species, including the iconic bird-of-paradise for which New Guinea is famous.

Bruce Beehler, a biologist who has extensively studied the birds of New Guinea, described the TransFly as “exceedingly biodiverse” and “filled with wildlife of all sorts.”

Before the deforestation began, villagers told us, they could find food a few steps from their homes. It was common to see cassowaries – a flightless bird a little like a turkey – in their backyards. Boar and kangaroos roamed around the village, and the swamps were full of fish.

Still, some villagers welcomed the arrival of Medco. The company assuaged concerns over the potential impact of its project by handing out large amounts of cash and making a string of promises that were both reassuring and alluring.

According to villagers we interviewed, and documents obtained by the Indonesian magazine Tempo in 2012, the Marind were told they would get jobs, support for their children’s education, and a new school, church and health facilities.

The company also signed a written agreement in 2009 committing it to protect sacred places, areas of cultural importance, hunting grounds, and what Medco described as “other places considered important to the community.”

“At the beginning it was good, because the people got jobs,” said Amandus Gebze, a Marind father of nine. “Everyone was involved in the work, there were no exceptions.”

But within a few years, the villagers were fired. The regular income Medco had provided dried up.

Asked why the employees had lost their jobs, Medco first explained in a written statement that it stopped clearing the forest in 2014 because it was losing money. But it added that it had switched from employing staff directly, to working through “contractors or third parties.”

The company then suggested the villagers had lost their jobs because they were unable to “comply with company regulations” and were “often absent,” and were therefore considered to have resigned.

Some villagers returned to hunting to provide food for their families. But by this point, an area of forest north of the village running some ten kilometres east to west had been cleared, to make way for a monoculture tree plantation.

In interviews, nine villagers said it had become significantly harder to source their traditional foods. They had to roam much further, as far as the Bian river, some 15 kilometres away, to hunt. They could now spend several days hunting without finding anything.

Amandus said that if he is able to find cassowaries or deer, animals that were once abundant, he sells the meat. “It’s just the bones that we eat, boiled,” he said.

Villagers also claimed the company’s operations have also polluted the sago groves around Zanegi. They alleged that while the sago groves had been spared from clearing, the denuded landscape around them allowed mud and chemicals to flow in.

There were still some less secure jobs associated with Medco’s operation. Some of the families we interviewed spend their days gathering what is known as leles, the small pieces of wood left after the forest is cleared.

They work in groups, bringing along entire families, including children, to help. They can earn around $5 for each cubic metre – amounting to several hundred kilos of timber – they gather.

Medco suggested that the villagers are better suited to this irregular work. By engaging in gathering leles and “independent logging,” the company wrote, “the surrounding community can manage their work time and income according to their abilities.”

Medco told us that it has written standards that prohibit the use of child labour, including through “self-managed” work, but that the Marind violated the terms of “work agreements” to involve children in it. “[I]t is their culture to always bring their families everywhere, whether hunting or other activities,” the company wrote.

With the cash villagers generate from gathering leles or hunting, supplemented by government handouts, they buy food brought in by pick-up truck. This food attracts prices higher than in a high-end supermarket in Jakarta, the nation’s capital, our reporter found.

Without a secure income and their traditional food sources declining, some villagers told us it has become common for them to eat only rice, a meal they refer to as nasi kosong or “empty rice.”

One day in April 2022, The Gecko Project observed Amandus Gebze’s family prepare a breakfast of rice with two packets of noodles, split between the parents and six siblings.

Some families will sprinkle pepper on the rice to make it edible. Others will pour salt water on it or just drink large quantities of water to help them swallow it. “Rice, with water to push it down,” said Blandina Balagaize, a mother of six, when asked about her family's diet.

The warning signs that Medco’s project was damaging the Marind’s food security have been present almost from the outset. Recordings of interviews with villagers in 2010, carried out by a local nonprofit, show that they were already expressing concern about the impact deforestation was having on their sago groves and hunting grounds.

A 2012 film focusing on Zanegi captured the village nurse carrying out a check on the emaciated body of an infant named Herlina, warning that she was suffering from malnutrition. The nurse claims that cases of malnutrition have risen sharply.

Early in 2012, within months of the film being shot, Herlina died in a hospital in Merauke city.

“We were so angry,” her mother, Persila Samkakai, told us. “She was our first child. How could it be possible?”

The following year, the Forest Peoples Programme, a UK-based group that advocates for the rights of indigenous peoples, warned that disease and malnutrition were “rampant” in the village and five children had died in 2013 alone. The group said there was “flagrant evidence of the severe food insecurity faced by the community as a result of the loss of their customary lands and livelihoods to incoming investors.”

Medco said that it had sent a team to Zanegi to investigate these allegations. “Based on the results of the investigation, no pollution was found due to the company's activities in water sources and swamps in Zanegi village,” the company wrote in a statement.

Nonetheless, malnutrition still stalks the village.

In interviews with our reporter in April 2022, health workers stationed in the village said that four children were stunted – meaning that they were shorter than they should be for their age, an indication of impaired development because of a lack of nutritious food. Eight pregnant women were suffering from chronic energy deficiency, a consequence of malnutrition that poses risks to both mothers and babies.

Health records obtained during an investigation by the Indonesian newspaper Kompas in August last year showed the number of stunted children had climbed to 14, around a third of all the young children that had been measured.

Since 2012, there have been reports of a total of nine malnourished children from Zanegi dying, including Herlina. Kompas found that between 2019 and 2021, one family alone lost three children.

Medco rejected the suggestion that this could be linked to its project. “Medco Papua's operations do not cause malnutrition,” it wrote. “No community food sources were disturbed.”

However, it also said that the “allegations presented by The Gecko Project regarding malnutrition incidents require further in-depth investigation”.

Medco denied making promises to the community, beyond the written agreement to protect their food sources and other key areas. It insisted that it had made efforts to help improve the plight of the community, despite the fact its project was losing money.

Medco claimed that its project’s progress was limited to 3,000 hectares of land because it was not financially viable. This is supported by satellite imagery, which shows the forests around Zanegi being cleared rapidly after 2010, then largely stopping in 2014.

But in 2017, the Indonesian government gave Medco’s failing project a new lease of life. It provided financing to help Medco construct a new biomass power plant in Merauke, while the state-owned electricity company committed to buying the energy it would generate.

With new domestic demand, and millions of dollars in government support, Medco would no longer need to export wood chips overseas.

Satellite imagery shows the new power plant emerging, 20 kilometres south-east of Zanegi, in late 2018. In 2021, it also shows deforestation resuming, north of Zanegi.

“Green” financing

The first tranche of government funding came from PT Sarana Multi Infrastruktur (SMI), a state-owned company under the control of the Ministry of Finance. According to company documents, in 2017 it provided 60 billion rupiah (then almost $4.5 million) in “project financing” for the power plant.

SMI was established to provide infrastructure financing, but has been increasingly focused on helping Indonesia meet its climate change commitments. Its 2017 sustainability report suggested that Medco’s power plant could help Indonesia deliver on the Sustainable Development Goals. In a 2020 presentation, an SMI director presented the plant as an example of “financing to contribute towards climate change mitigation.”

The Sustainable Development Goals are a set of targets adopted by the United Nations in 2015, aimed at protecting the environment and ending hunger and poverty. At the time SMI signed an agreement with Medco, however, nonprofits had already alleged publicly that the project was having a devastating impact on the food security of the Marind.

These allegations had been raised twice with the UN, in the years leading up to SMI providing this financing.

SMI declined to be interviewed or answer written questions about how its support for the power plant was consistent with the Sustainable Development Goals or protecting the environment, or whether it had taken steps to identify whether the project could harm the Marind.

In 2021, the Ministry of Energy and Mines and Medco mentioned in a webinar that another government fund, the Indonesian Environment Fund, or IEF, had also provided “funding support” for Medco’s Merauke operation. Budi Basuki, a senior Medco executive, said that the total funding had reached 140 billion rupiah, more than $9 million.

The IEF was established in 2019 as a body that could be used to channel investments to protect the environment. Its role in financing Medco’s project is striking because it has also been used as the body through which the Norwegian government has channelled tens of millions of dollars as a “reward” for reducing deforestation.

In 2022, Norway announced a payment of $56 million into the environment fund after the rate of deforestation in Indonesia fell. Several other international donors, including America’s aid agency USAID and the World Bank, have also pledged to put money through the IEF, in order to help Indonesia reduce its emissions from deforestation and land use.

Medco had cleared an estimated 3,000 hectares of forest for its plantation before it secured the financing. The company said it needs to almost double the size of its plantation to meet the demands of the power plant, and that it would continue to use wood harvested from the forest as it is cleared.

It also hopes to triple the capacity of the plant, creating demand for more land and wood.

Government maps show that as of 2012, large areas of its concession were intact, or “primary”, rainforest and swamp forests. Analysis of satellite imagery by The Gecko Project indicates that the area remains largely undisturbed. These landscapes hold large amounts of carbon that is released if they are cleared.

Endah Tri Kurniawaty, of the IEF, pointed to the fact that the area had been designated a “production forest” and said that it was therefore legitimate for Medco to cut the forest and replace it with a plantation. “According to the existing laws and regulations, they may do that,” she said.

The Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment declined to comment on the IEF’s financial support provided for Medco’s biomass plant. “We do not find it appropriate for Norway to comment on projects that are not related to the Norwegian Contribution,” it wrote in a statement.

It added that the Norwegian money would only be used to fund activities that “support the priorities” agreed between the two countries, and that the IEF “now has in place a comprehensive Environmental and Social Safeguards Framework.”

Endah said during an interview that the IEF’s safeguards should be public. But the team responsible for the safeguards subsequently declined to share them.

Co-firing

Policies announced by the Indonesian government over the past two years suggest that its support for Medco’s power plant is not an aberration.

To curtail its greenhouse gas emissions, Indonesia needs to rapidly wean itself off coal, its single biggest source of energy. Rather than shutting down its coal-fired power plants, it plans to keep the furnaces burning but phase out a portion of the fossil fuels by “co-firing” with biomass. Last June, the minister of energy and mineral resources, Arifin Tasrif, identified this kind of “co-firing” as central to its strategy for reducing emissions from coal.

While the Merauke operation is small compared to the network of vast power plants spread across Indonesia, dozens of them are also burning biomass. The state energy company, PLN, announced in 2022 that it planned to increase its use of biomass five-fold over the next year, and had set a target of burning 10.2 million tonnes across more than 50 power plants by 2025.

According to PLN, by 2022 the majority of its biomass came from waste, like sawdust, rice or palm oil husks. But to meet the massively growing demand it needs timber plantations.

The ministry of environment and forestry has rallied behind the policy. At the UN climate conference in Egypt last November, Agus Justianto, the director general of sustainable forest management, said that it would “promote plantation forests for energy development” and that more than a million hectares of “production forest” could be used.

Trend Asia, a nonprofit organisation that has been monitoring the policy, calculated that meeting this demand would require at least 2.3 million hectares of land to be converted to plantations – an area half the size of Denmark. The organisation has raised the alarm that this risks increasing deforestation.

Timber plantations can be established on “degraded” lands, as the government has suggested could happen now. But as with Medco’s project, they have often been planted in place of rainforests, which has the advantage for investors of generating a steady-stream of timber before the plantations reach maturity.

“The use of biomass is renewable in theory, but in practice it is not,” said Yuyun Indradi of Trend Asia. “Timber plantations have been a major driver of deforestation. So our concern is that it’s very likely this will trigger deforestation.”

“There’s no hope”

In Zanegi, the Marind have now spent more than a decade observing how policies decided thousands of miles away – and the whims of a corporation – can influence their lives.

Natalia Mahuze, wife of Amandus Gebze, stood barefoot with her son Efrem under the shade of a tree in Zanegi, one day in April 2022. Natalia carried her nine-month old son with her right arm and used her left to keep three-year-old Efrem from straying.

Three pregnant mothers joined them. They chatted to one another while waiting for the midwife to come out from her house, which was attached to the village health centre. A shabby building, its once-white paint was fading and turning brown with spots of mud.

The midwife emerged with a digital body-weight scale. She called Efrem’s name and his mother guided him into the scale: 10.7 kilograms – underweight for his age. The midwife measured his height and head circumference using a blue soft ruler, and noted the measurements in his health record.

She handed Efrem a pack of biscuits to supplement his diet, and took a photo of him holding the packet with her mobile phone. She gave another to his mother.

“Please don’t share these with his siblings,” the midwife told Natalia. “They’re only for him.”

Efrem was born around the time Medco completed construction of its power plant in Merauke.

“It used to be good,” Natalia said. “It’s really hard now.”

Her husband Amandus, once optimistic about Medco’s project, questioned whether it would ever deliver for his family.

“If they want to develop the community, they’ll need more of our territory,” he said. “If we have to give them more land, is there any chance they’ll show more concern for us? There’s no hope.”

Read more reporting from The Gecko Project on food security here.

Sign up to our mailing list here.