- The now-concluded investigative series “Indonesia for Sale” examined the corruption underpinning Indonesia’s land rights and climate crisis in unparalleled depth.

- The series was a collaboration between Mongabay and The Gecko Project, an investigative journalism initiative founded at Earthsight in 2017.

- In this final commentary, we explore how tackling corruption is an essential precondition for Indonesia to meet its climate targets and resolve land conflicts, and the role of government and civil society in doing so.

Just over two years ago, The Gecko Project and Mongabay set out to investigate the hidden story behind twin environmental and social crises unfolding in Indonesia.

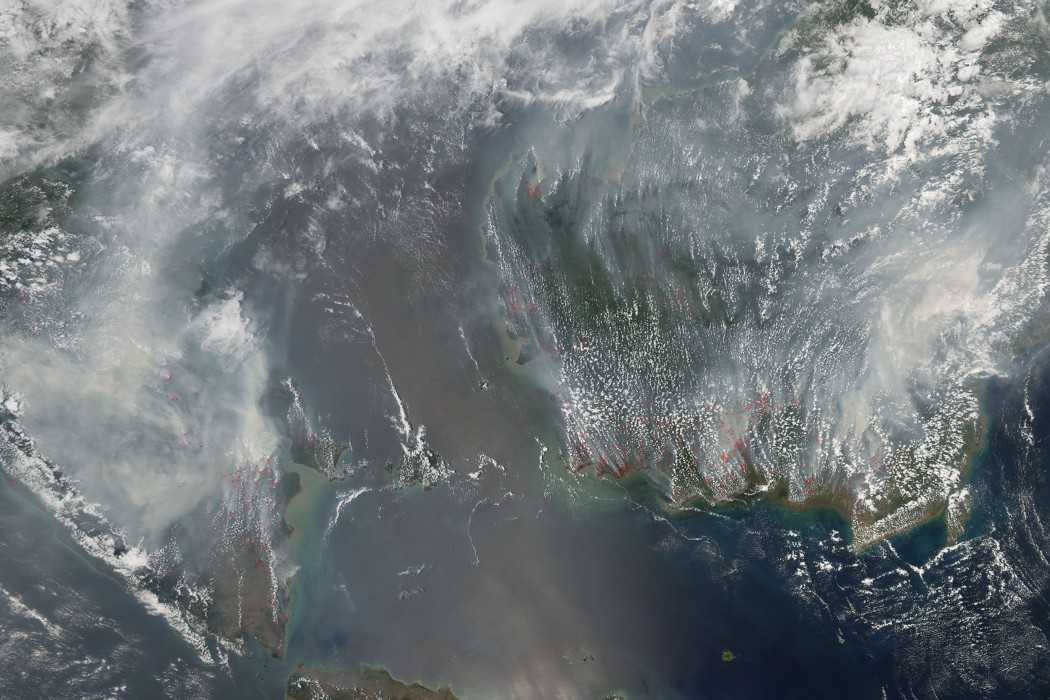

The country’s rainforests, the third most expansive in the world, were falling at the highest rate since detailed measurements began. Every year, carbon-rich peat swamps across the archipelago were drying out and turning into a conflagration, churning noxious greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. In thousands of villages across the archipelago, people found themselves locked into intractable conflicts with their neighbours, companies and the government, over control of land.

The common thread was the proliferation of industrial-scale plantations, to produce palm oil and other commodities. For more than a decade, these giant estates were the leading cause of deforestation in the country. The conflicts over land emerged as the ancestral forests and farmlands of rural communities were transferred by the state to the companies behind the plantations.

These were crises of global significance. Indonesia was releasing as much greenhouse gases by destroying rainforest and peatlands as some of the world’s most developed nations were doing by burning fossil fuels. In the late 2000s, it shot to the top of the list of emitters, below only China and the U.S., solely for this reason. The transfer of community lands to companies owned by oligarchs was symbolic of an assault on marginalised, rural communities with insecure legal rights across the Global South.

Indonesia’s role in the climate crisis attracted global consternation, and also a rush to find solutions. The Indonesian government repeatedly pledged, on the international stage, that it would reduce deforestation to meet its climate targets. The Norwegian government committed $1 billion to incentivise diverting new plantations away from the rainforest. By 2014, the biggest companies controlling the production and trade of palm oil had pledged to stop clearing forests for new crops, and to end to their exploitation of rural communities.

Our research led us to the hypothesis that a rich vein of corruption was underpinning these crises.

But amid all this, there was a missing part of the narrative: a lack of focus on who had really made the decisions that took us to this point, and their motivations in doing so. Over the previous few years, research by the reporters who came together under this new joint project led us to the hypothesis that underpinning these crises was a rich vein of corruption. Further, that this corruption was not marginal to the central problem — a question of a few politicians taking a cut here or there from projects that would have gone ahead anyway, an informal tax. It was something fundamental to it. An enabling factor that could not be ignored if these solutions — whether from the Indonesian government, international community or private sector — were to succeed.

This hypothesis rested on the principle that Indonesia was a highly decentralised democracy, in which district chiefs, or bupatis, held considerable control over licensing for palm oil plantations.

They had greenlit this proliferation of plantations that were driving land conflicts, but they were also elected by the people most deeply affected by those conflicts. Why were they not preventing the surge of plantations onto the land of the people who elected them? Was there some other, unseen, imperative driving their actions?

To find out, we set out to meet the people who moved in this world: the politicians; middlemen and fixers who occupied the murky space between business and politics; Jakarta lawyers who screened land deals; staff at major plantation firms; whistle-blowers and activists; and prosecutors at Indonesia’s anti-graft agency, the KPK. Our investigations, detailed in the series “Indonesia for Sale,” revealed that district chiefs have systematically exploited their control over land amid a near-complete lack of oversight, to make millions of dollars by selling permits to major plantation firms. They were doing so both to profit themselves, and to finance election campaigns that would return them to office, creating a negative cycle of corruption.

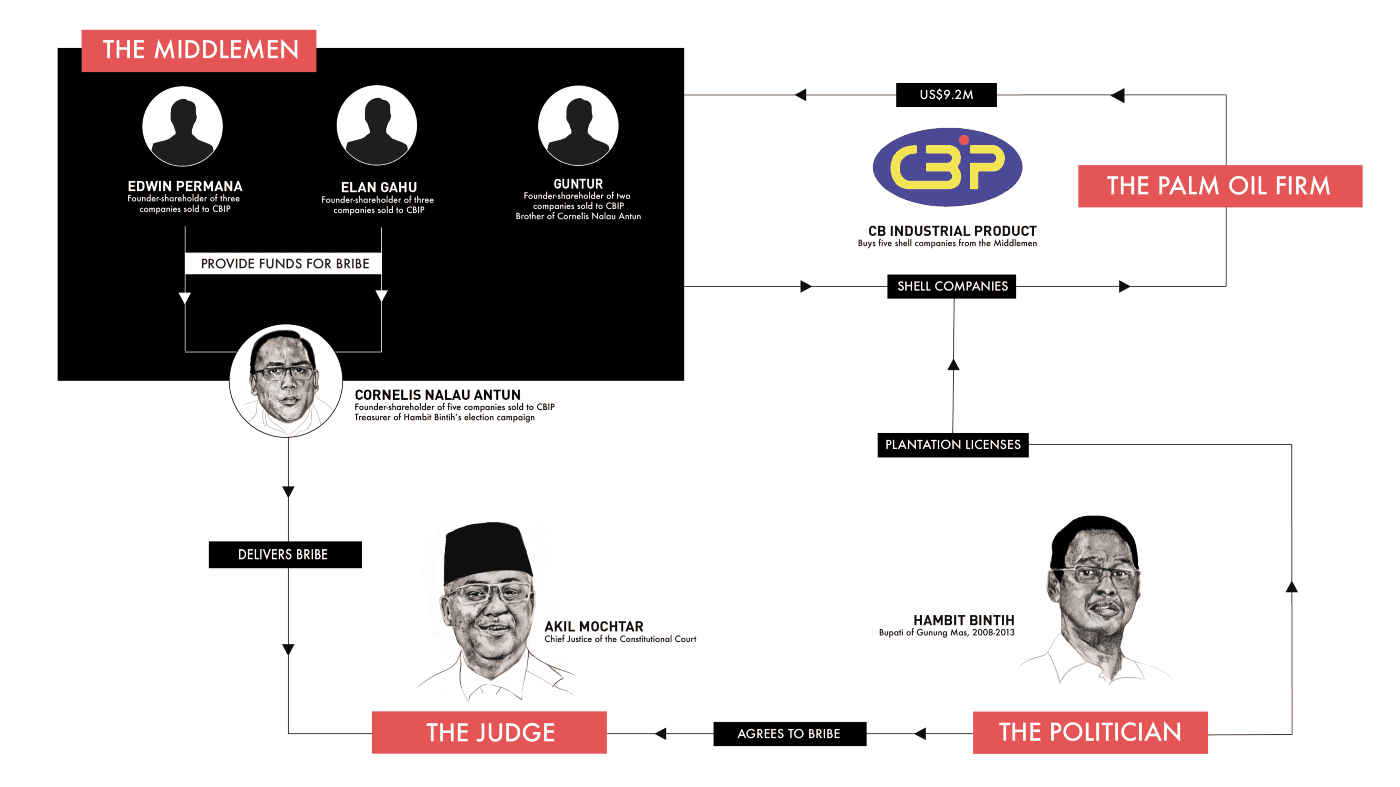

District chiefs and their cronies conjured assets out of thin air by creating shell companies and endowing them with permits. These assets, which existed only on paper, were traded to multinational firms based in Kuala Lumpur, Singapore and Dubai, with access to millions of dollars in capital from international banks. Some of those who benefited from these schemes sought to hide their involvement through crude, if effective, means — placing fake names and addresses on company documents. Others used more sophisticated and watertight methods, registering their companies to anonymous consultancy firms in offshore tax havens like the United Arab Emirates.

District chiefs and their cronies conjured assets out of thin air. These assets, which existed only on paper, were traded to multinational firms.

We discovered that major plantation firms were quite content to buy assets from the family members and cronies of district chiefs. In some cases, they had literally got into business with them. These were the same firms that later made commitments to end deforestation and “exploitation.” Our exposés showed that the money to be made by politicians incentivised them to issue ever greater numbers of permits, covering almost every corner of viable land in their jurisdictions. But also to rail against any attempts, particularly by local communities, to control the plantation firms in ways that might have mitigated their worst excesses.

We also discovered a concrete link between graft in land deals and dark money in regional elections. Politicians used permits and land deals to finance their corrupt campaigns. This ensured that the problems became more deeply entrenched, as incumbents rode back into office on the shoulders of plantation firms. Our second major investigation revealed how the money used to bribe Akil Mochtar, the then-chief justice of Indonesia’s Constitutional Court, to decide an election in favour of an incumbent bupati from Borneo, flowed directly from a deal for plantation permits involving a Malaysian firm.

Our sources in government and the private sector were clear that we were not looking at isolated cases. We were looking at a system. Through our investigations we identified the contours and infrastructure of this system: how the deals work, how the assets are created, how they’re hidden, how the money flows into elections, and how this system serves to block solutions. We also demonstrated how the companies positing themselves as part of the solution are deeply involved in this system.

Once you understand that system, you see it in play across Indonesia, as companies hoover up permits during election season, district chiefs side against communities, and legal safeguards are ignored. It is a system of governance not laid down in a statute book, but one no less real for that — an uncodified set of rules playing out in high-end Jakarta hotels and backroom deals.

It is a system of governance not laid down in a statute book, but an uncodified set of rules playing out in high-end Jakarta hotels and backroom deals.

In this system, the exercise of power is both grubby and sometimes farcical. In one case, a politician signed permits while he was supposed to be in prison for corruption. During an interview, he shrugged and dismissively told our reporting partners, Indonesia’s Tempo magazine, that he was technically still “in office” at the time, as he had not yet been convicted of the crimes for which he stood accused. In another, political players negotiated bribes via text message by referring to “tonnes of gold,” before cash from a land deal was delivered to the front door of a judge.

One politician, who had made a fortune by selling permits issued by his father, a district chief in Borneo, to a firm owned by Indonesia’s billionaire Rachmat family, told us in a Trumpian flourish that he would never do business in his own district because he was duty-bound to act as a “referee” between communities and companies. His elusive answer inadvertently pointed to the truth: he and politicians like him were not the rule-keepers they purported to be. They were playing one side, in a distinctly uneven game.

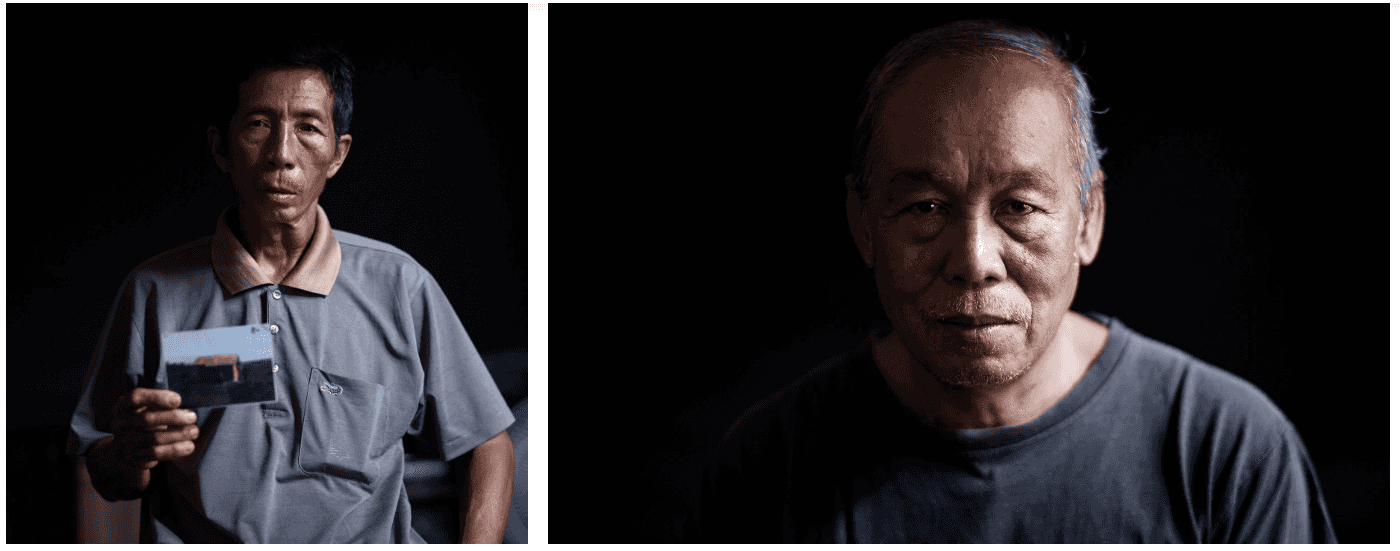

Our hypothesis, that these crises are underpinned by corruption, was supported by the evidence we found. But it was also a sentiment we heard time and again from the communities most deeply affected by these crises and the activists fighting on their behalf against the system. We repeatedly encountered the view that something had gone very wrong, and that it was fundamentally about democratic accountability. Our interviewees viewed the wrongs that had been perpetrated against their communities, and the wanton environmental destruction, as a symptom of a government working against its people due to collusion with private companies.

“[Companies] destroy the structure of government so they can legalise their land grabs,” one village leader from East Kalimantan told us. “We came up against our own government, because they were in on it too,” said a woman from Aru, a remote archipelago that was saddled with two dozen permits for sugar plantations by a politician later convicted of corruption.

These Indonesians are grappling with a fundamental question: why don’t we get policies that protect people and the environment? The pat answer is that it’s difficult to balance environmental protection with economic growth. But here, the root cause is corruption. A powerful cabal of local politicians and companies have conspired to systematically exploit weak points in governance to benefit themselves and increase their profits, at the expense of any other imperative — notably, to protect the natural world, and to respect the fundamental rights of the people who live in these places.

This phenomenon is not unique to Indonesia. In Brazil, huge gains were made in protecting the Amazon and rights of indigenous peoples in the 2000s, while simultaneously increasing production of agricultural commodities. But these gains are being systematically undone due to the advancing influence of the agribusiness lobby. A recent investigation by Repórter Brasil found that a quarter of the members of the new Congress had received campaign donations from agribusinesses accused of illegally clearing forest or using slave labour. Protected areas are being wiped out by cattle ranching, while the government changed the law to legalise such acts. The beef from these ranches finds its way into the supply chains of the world’s biggest meatpacker, the Brazilian-owned JBS. JBS, which channels its profits through the Cayman Islands, was itself fined $3.2 billion for its role in a corruption scandal that rocked the country.

The same pathology can be identified anywhere a globalised agricultural industry comes into contact with states rich in land and weak in governance.

The International Criminal Court in The Hague has broadened its process for selecting cases to encompass land grabs and environmental destruction, a decision prompted in part by the grand corruption driving these crimes in Cambodia. Villagers there have been driven from their land at the point of a gun, to produce sugar and other cash crops for companies controlled by regime cronies. The entire state is so in hock to them that the courts are viewed as incapable of applying the law, other than to serve the interests of land grabbers. The same pathology, to varying degrees, can be identified anywhere a globalised agricultural industry comes into contact with states rich in land and weak in governance.

So what could change this picture in Indonesia? The government has mandated a review of all outstanding licenses for oil palm plantations in the country as part of an official freeze on new plantations. Such a review could delve into the circumstances under which the permits were issued, evidence that they were expedited, or legal safeguards eschewed; they could examine the history of ownership of shell companies routinely used to trade plantation permits; they might examine the timing with which the permits were issued, and when they were sold, and compare them to elections in relevant jurisdictions. Our investigations indicate that such analyses would provide a groundswell of evidence that would, in turn, provide leads for the anti-corruption agency to pursue and prosecute. They might provide sufficient grounds for millions of hectares of unexploited licenses to be revoked, providing space for a more balanced development model to be pursued.

The review could also examine the treatment of rural communities in the land acquisition process: what promises were made to them and what was delivered; and whether existing rights were respected. It might give rise to proposals for restitution of land annexed either illegally or using laws for which the constitutional basis is steadily eroding. The government could make use of a year-old regulation on beneficial ownership to investigate and expose trade in state assets by politicians, their families and cronies. They could pursue evidence of tax dodging, aggressively pursuing the shifting of assets and capital into foreign jurisdictions, making use of international treaties and forums.

While this might amount to a wish list that seems implausible with the current levels of political will, over the past two years the picture has begun to change. A greater number of investigations have been carried out into the subject of collusion and the business interests of Indonesia’s political elite. Tempo, the leading magazine in the country, collaborated with us to investigate land deals in Papua. Katadata published an in-depth series on illegal coal mining, tax evasion and the “intimate” relationship between businesspeople and state officials. A documentary film examining the links between Indonesian coal companies and the country’s political elite, Sexy Killers, was viewed 10 million times within the first three days of its release on YouTube.

NGOs have begun to map out the private interests of leading politicians, the use of “shadow companies” to mask corporate structures, and tax evasion. Dozens of indigenous activists across the country are seeking public office, their eyes open to the challenges they face from dark money. The subject of land concentration was given the highest-profile airing possible, when the incumbent President Joko Widodo criticised his challenger, Prabowo Subianto, for his own extensive plantation interests during a televised campaign debate.

The KPK is promoting legal reforms that would address loopholes; it is pushing the boundaries through case law.

The KPK carried out an assessment of mines across the country that led to the cancellation of hundreds of permits. It has now turned its sights on palm oil. Though it is stymied by loopholes in the corruption law, as our analysis showed, the agency is promoting legal reforms that would address precisely these gaps. It is pushing the boundaries through case law, asking judges to consider environmental damage and not just strictly monetary state losses as a critical factor in corruption cases.

Journalists and NGOs are also building pressure on a global financial system that allows assets and money to be hidden in offshore tax havens. The Panama Papers, the OCCRP’s Troika Laundromat and other investigative projects by journalists around the world have raised the profile and understanding of how aspects of the transnational financial system are exploited by the corrupt. These explosive stories have led to a growing recognition that these secrecy jurisdictions, which facilitate misdeeds in Indonesia, must be opened to greater scrutiny.

Over the past couple of years, the pace of deforestation in Indonesia has begun to slow, especially within the boundaries of existing oil palm concessions. The temporary freeze on new licenses is holding, and consumer pressure on the palm oil industry appears to have led to genuine impact on clearance by some plantation firms.

In the absence of deeper reform, Indonesia is set to miss its climate targets by a significant margin. There is no prospect that land conflicts will be resolved or future occurrences mitigated.

But how real are these gains? And is there enough momentum? The moratorium is, and was always intended to be, a temporary plaster, not a cure. Palm oil is traded at half the price it reached in 2011. If commodity prices rise again, the economic incentives to resume deforestation will be irrepressible, as long as the fundamental political conditions remain the same. In the absence of deeper reform, analysis by the Washington-based World Resources Institute indicates that Indonesia is set to miss its climate targets by a significant margin. On the current trajectory, there is no prospect that land conflicts will be resolved or future occurrences mitigated.

Our findings indicate that for meaningful change to occur, politicians cannot be allowed to take unilateral decisions, in a vacuum of transparency, over the fate of large numbers of people with huge environmental implications. They must be subject to scrutiny, with checks and balances provided by both institutions and informed citizens. In such an environment, it is quite feasible that plantations could continue to expand, while other imperatives — existing livelihoods, the climate, biodiversity — are also taken into account. But there must be greater transparency over corporate ownership, and the personal interests of politicians, to reveal who will benefit from decisions.

To address the roots of cases such as those we have explored will also demand action by governments beyond Indonesia’s borders. Action is needed in the countries whose consumption of commodities like palm oil is fuelling the fire. It is also needed by countries whose lawyers and bankers are being allowed to act as key enablers, through no-questions-asked finance and a welcome haven of secrecy.

Politicians cannot be allowed to take unilateral decisions, in a vacuum of transparency, over the fate of large numbers of people with huge environmental implications.

In the absence of fundamental changes within the political system, those outside it can still change the environment in which politicians operate. An engaged citizenry watching, asking questions, pushing for information without remorse can close the space for corrupt acts to occur, while simultaneously building momentum for institutional reforms. They can investigate and expose how decisions are made. Watchdogs and reporters can follow assets, money and commodities as they flow overseas, tracking culpability for the acts carried out in the hinterlands of islands like Borneo and Papua.

“Indonesia for Sale” has now come to an end. But The Gecko Project, Earthsight and Mongabay will continue to pursue the wealth of investigative leads and fascinating stories across Indonesia, and will also be expanding these in-depth reports to Brazil. Readers can expect more long-form reporting, analyses and films from the front line in the coming months.

The Gecko Project, which was established at Earthsight in 2017, has now been established as an independent organisation in its own right, dedicated to reporting on the intersection of corruption, land rights and the environment.