- In a year-long investigation with The Gecko Project, the Korean Center for Investigative Journalism-Newstapa and Al Jazeera, Mongabay traced a $22 million “consultancy” payment connected to a major land deal in Indonesia’s Papua province.

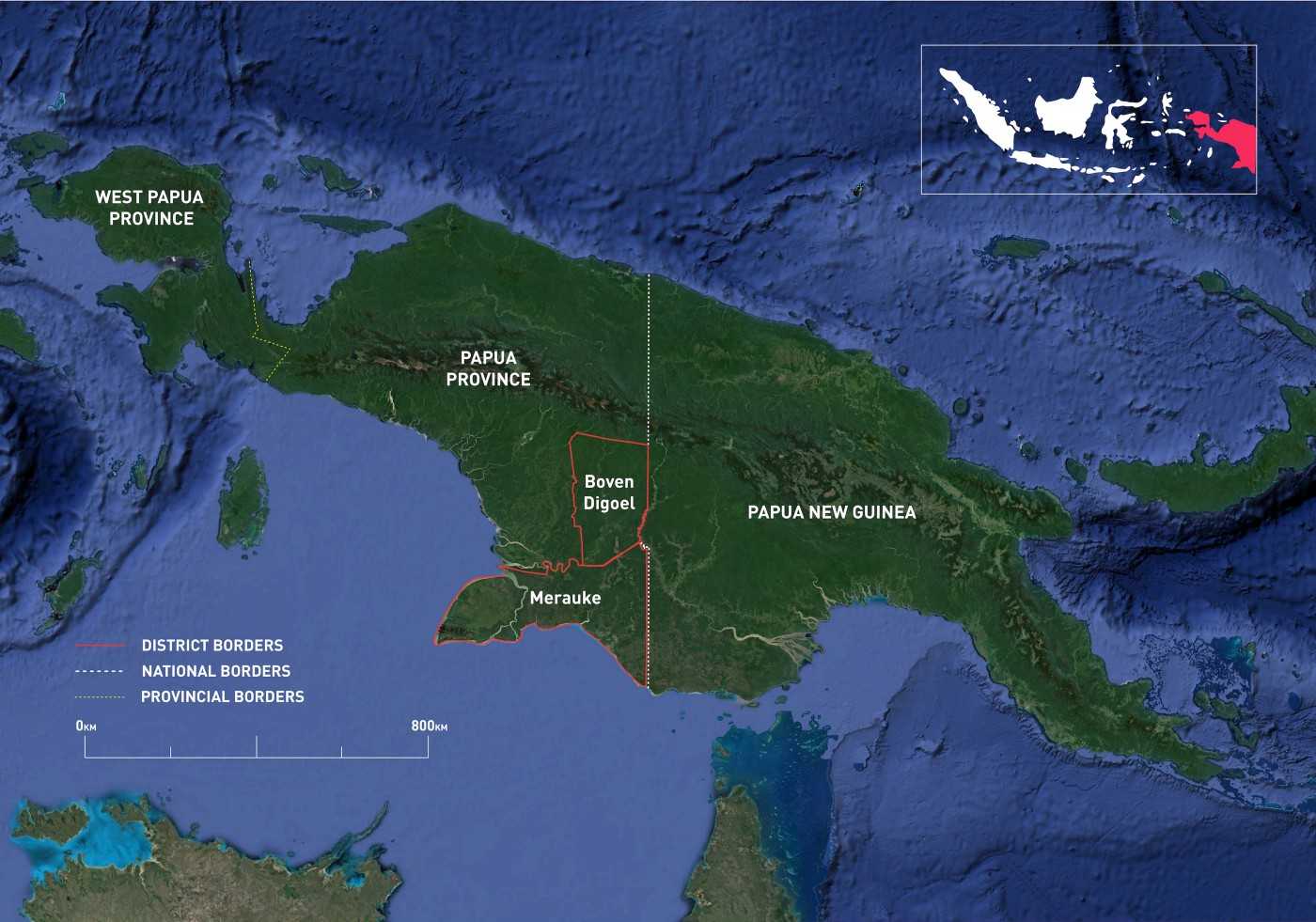

- It took us from South Korea and Singapore to the heart of the largest rainforest left in Asia, to find out how the payment helped make the Korindo Group one of the largest oil palm producers in the region.

- Photography by Albertus Vembrianto.

Part 1: ‘Maybe they didn’t expect us to find it’

In April 2019, an Indonesian delegate stepped onto the stage at a conference hosted by Interpol, the international police organisation, at its Singapore headquarters. Among the audience were dozens of law enforcement agents from across the world, there to learn about how white-collar crimes and corruption underpinned the ongoing destruction of the world’s rainforests.

Interpol’s interest in forest crime had been stimulated by the billions of dollars the World Bank had calculated developing countries were losing in tax revenues to the global trade in illicit timber every year. There was a growing recognition among enforcement agencies that the crime scene was not only in rainforests. It was also in the dark recesses of the global financial system, through which bribes were paid and profits laundered.

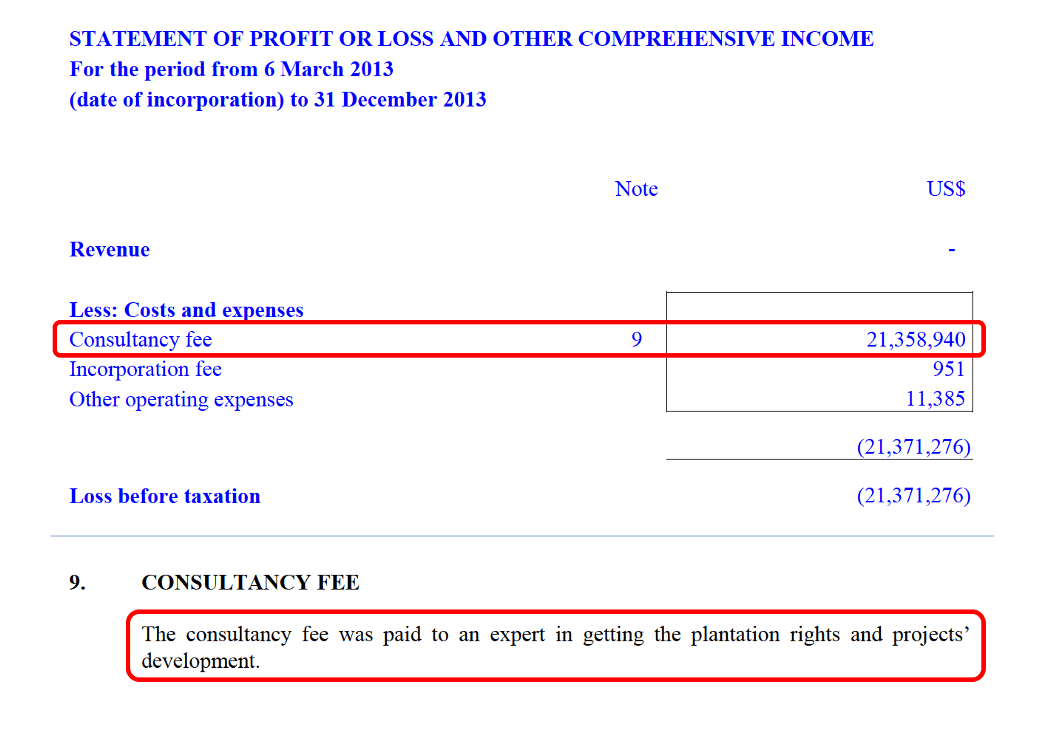

The delegate, from an Indonesian nonprofit, walked the audience through a “suspicious” $22 million payment made by a conglomerate, which she declined to identify in her presentation. In corporate filings, the transaction had been described as a “consultancy fee,” paid to an unnamed “expert” who had helped obtain the rights to develop a vast oil palm plantation in the Indonesian province of Papua.

It was a curious payment. In Indonesia, permits for plantations have no significant official costs, the delegate noted, as dozens of suited enforcement agents watched from the auditorium. But the government officials who preside over the sector have a notorious propensity for corruption.

In fact, the delegate said, the payment bore the hallmarks of a common ruse deployed in major transnational corruption schemes, in which sham consultants are used to channel millions of dollars to officials in exchange for contracts or permits. Was this “consultant” simply an “intermediary for bribes paid to Indonesian public officials?”

“Maybe they didn’t expect us to find it,” the delegate, who asked to remain anonymous, later told us. “I think they were being careless.”

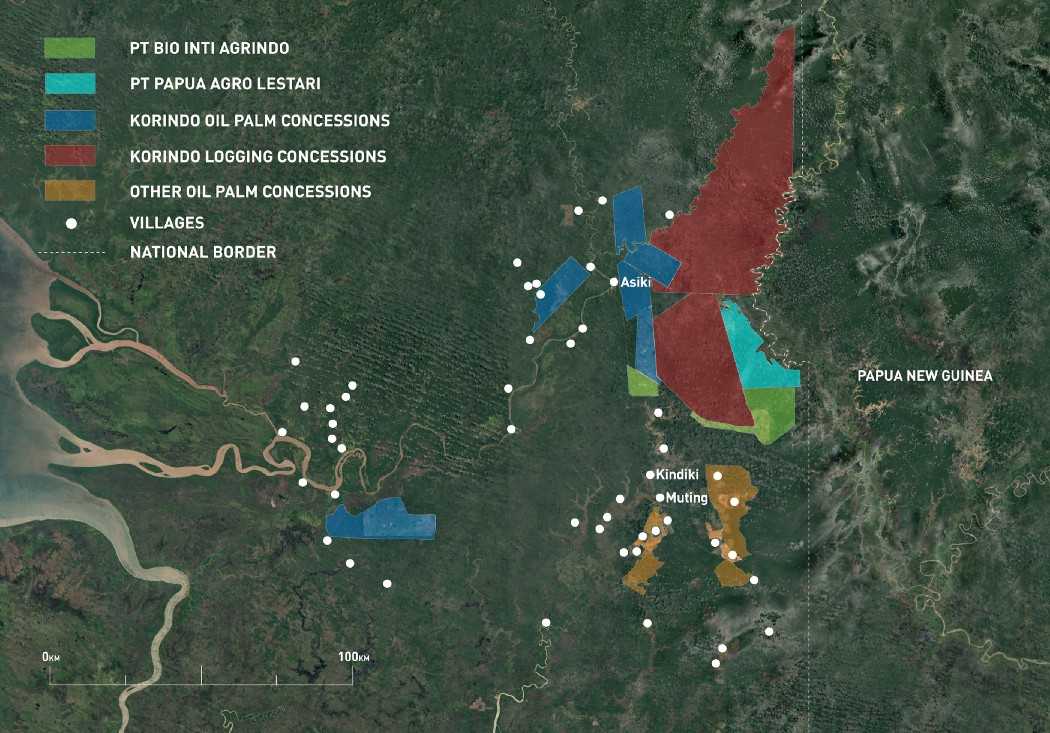

The company in question was the Korindo Group, a privately owned conglomerate that has been logging Indonesia’s rainforests since the 1970s. The payment was made at a critical juncture as Korindo rapidly grew its operations in Papua. Between 2009 and 2014, through this deal and several other concessions for which it obtained licenses directly from the government, Korindo acquired the rights to an area of land in the province twice the size of Seoul, the South Korean capital.

As other major palm oil producers, under pressure from environmentally conscious buyers, pledged to stop clearing rainforest, Korindo plotted a different course. Since 2013, it has cut down 25,000 hectares of rainforest in Papua, at the heart of one of the most important ecosystems left on the planet.

Korindo’s explanations for the payment have shifted over time. When we asked about it this year, the conglomerate said the payment was not a consultancy fee at all. It was part of a share purchase, Korindo said, from a man named Kim Nam Ku, who had sold Korindo a shell company holding permits for the plantation. Korindo told us that Kim chose to mischaracterise the payment as a consultancy fee, for reasons only he could explain.

Over the past year, The Gecko Project and Mongabay — in collaboration with the Korean Center for Investigative Journalism-Newstapa and 101 East, Al Jazeera’s Asia-Pacific current affairs program — have investigated this payment and the role it played in Korindo’s expansion in Papua.

We reviewed corporate records, financial statements and permits dating back more than a decade to examine how Korindo had expanded its landbank. We traced the group’s complex ownership structure, from Indonesia, through Singapore, to multiple notorious tax havens, discovering how it deploys corporate secrecy techniques that prevent scrutiny of key aspects of its business.

We travelled to Papua on the trail of Kim Nam Ku, to find out what he had been up to in one of Indonesia’s remotest regions. Through interviews with his former colleagues, documents and a leaked cache of photos, we traced his career from the Papuan rainforests in the mid-2000s, through his role in an abortive attempt to establish a giant plantation project in Madagascar, to his multimillion-dollar dealings with Korindo. Today, Korindo controls more land in Papua than any other conglomerate, and it has assumed many of the functions of the state in one of Indonesia’s most neglected and militarised areas. We estimated that since the turn of the century, it had exported products worth $320 million using timber harvested as it cleared the rainforest for plantations in the province. But indigenous Papuans we interviewed said Korindo had failed to keep its promise to improve their lives through jobs and development. We found infants suffering from malnutrition, while palm oil worth tens of millions of dollars is exported from their land each year.

We asked 10 anti-corruption experts, including former U.S. officials with experience investigating transnational corruption schemes, to review details of the payment and other information we uncovered. They said it was impossible to tell whether the payment had financed bribery without using powers available only to government agencies. But they considered the payment closely resembled the typology of bribery cases involving consultants. They pointed to the outsized fee, the high risks of corruption in Indonesia, Korindo’s shifting explanations and multiple other “red flags” as evidence that the payment merited investigation by law enforcement.

“Was the company just turning a blind eye to the possibility that the ‘expert’ was passing on huge amounts in bribes to public officials and community leaders?” said Bruce Searby, a former U.S. Department of Justice trial attorney who prosecuted transnational corruption cases.

��“Was the company just turning a blind eye to the possibility that the ‘expert’ was passing on huge amounts in bribes to public officials and community leaders?”

Korindo categorically denies paying bribes. In a letter dated June 1, the head of Korindo’s legal team said that our findings, and especially any allegations of bribery, were “completely incorrect and false.” The conglomerate insists its plantations have benefited the Papuan people by providing jobs, education and healthcare. Further, it says it made a loss on the timber it harvested while developing plantations.

Conglomerates moving money through offshore companies and secrecy jurisdictions can present a challenge to law enforcement agencies bound largely by national borders. Korindo’s payment may never have entered Indonesia, placing it beyond the immediate reach of the nation’s regulators.

But it is likely the payment travelled through the banking systems of both Singapore and the U.S., countries that would be able to trace the payment at the request of the Indonesian authorities. U.S. agencies have a strong track record in assisting foreign partners in complex transnational financial investigations, and operate under laws that give them expansive powers to pursue evidence across the world.

Former officials from the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Department of Justice told us enforcement agencies should investigate the payment. It was not just a $22 million case, they said; the fallout in Papua, and the impact on indigenous people and the rainforest, raised the stakes.

The starting point for the case could be quite simple. By pulling the bank records and tracing the payment as it flowed through the global financial system, they might be able to answer the question: where did the money go?

Part 2: The chaebol

Seung Eun-ho, the founder of the Korindo Group, has told the origin story of his company many times. In 1975, he was in Indonesia working for his father’s timber business when crisis hit. His father, Seung Sang-bae, was arrested in their home country of South Korea on charges of tax evasion, and the company’s assets were seized.

The younger Seung had come to Indonesia a few years earlier to source raw materials. With his father facing bankruptcy, “the future seemed bleak,” Seung later recounted. “All I had was a logging permit.” Seung borrowed $1 million from an acquaintance, an executive in a Japanese timber firm, and invested it in logging equipment.

His new business, Korindo, flourished, and he repaid the loan within four years. Four decades later, he and his own son, Robert Seung, presided over a diversified business empire reportedly bringing in more than $1 billion in revenue each year. In the intervening years, Korindo had expanded its logging operations across Indonesia, built giant sawmills, planted seas of timber and oil palm crops. It moved into construction, paper manufacturing and shipping, and put Seung Eun-ho in the ranks of the super rich.

In glowing profiles in the South Korean media, Seung, now 78, is fond of recounting the scrapes he got into with rural Indonesians along the way: Madurese workers in Borneo who threatened to kill a South Korean employee after one of their own died in a car accident; Papuan separatists who kidnapped an executive, demanding $2 billion before he personally intervened to secure the man’s release. “They had no concept of money,” Seung said of the rebel fighters. “So I gave [the leader] cigarettes and sugar. Eventually, it was settled at $2,000.”

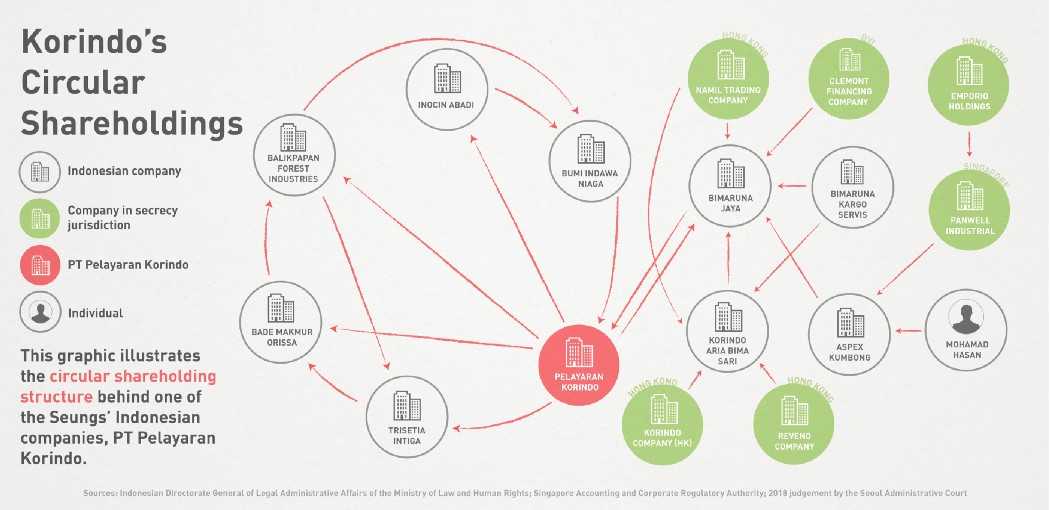

While Seung proclaims himself the founder and chairman of Korindo, unpacking who owns shares in the various companies within the group was almost impossible, until recently. For Indonesian companies, the names of shareholders are publicly available on a government database. These profiles revealed that the firms operating Korindo’s plantation and logging concessions were owned by other companies, which in turn were owned by other companies.

If you followed this line of shareholders back far enough, it would often loop back on itself, sometimes multiple times. The companies effectively owned shares in themselves, through what are known as “circular shareholdings.” Trying to find out who ultimately owned any one Korindo company was like getting lost in a rabbit warren. Where an endpoint could be discerned, it was invariably a company in an offshore tax haven, where shell companies are protected by corporate secrecy laws.

When Seung’s affairs were investigated by the South Korean tax authorities in 2013, however, it laid bare the extent to which Korindo’s structure was a carefully constructed facade that concealed the outright control he exercised over the entire group. The authorities discovered that Seung had set up 62 shell companies in the British Virgin Islands, Hong Kong, Panama, the Seychelles, Singapore and elsewhere that collectively owned Korindo’s Indonesian assets through circular shareholdings.

The paper shareholders and directors of these companies were nominees — Korindo employees who had “lent” their names to Seung and acted under his instructions, according to a South Korean court judgement. Others were secretarial firms which served to provide a front for individuals seeking to conceal their control of companies.

There were directorships, shares, even bank accounts registered in the names of these nominees. However, as held by the South Korean court, all were acting under Seung’s control and for his benefit. In 2018, the court ordered Seung to pay around $90 million in back taxes, a bill he had unsuccessfully challenged on the grounds he is an Indonesian citizen for tax purposes (he has appealed). The court decided that Seung’s use of complex, multilayered ownership structures and nominee shareholders appeared to be for the purpose of evading tax.

Other clues to why Seung deployed these methods lie in the unique evolution of corporate governance in the country of his birth. Circular shareholdings are a key feature of the giant, family-owned firms that dominate the South Korean economy. The chaebol, as these conglomerates are known, were a driving force in the nation’s rapid economic growth, transforming South Korea from an impoverished agricultural society to a global hub of high-technology manufacturing. But they grew so big that they were able to exert control over politics, often for their own narrow interests. Concern over their corrosive influence grew, erupting in a series of corruption scandals that peaked in 2017 when the heir of Samsung, the electronics giant, was convicted of bribing a former president.

“The chaebol chairman is like a god. He’s somebody who is untouchable within the company and it’s rare for them to have to take full responsibility for decisions that they’ve made.”

The chaebol deploy circular shareholdings in part because they enable the founding families to exercise outright control of their companies without appearing to do so, according to Geoffrey Cain, a journalist who recently published a book on Samsung. The structure dulls any accountability that might be in place in a traditional corporate structure, inuring the founders to the risks of bad behaviour and exacerbating their worst instincts. When prosecutors come knocking, Cain told us, “the board officers or executives who legally run the company will often take the fall and then the founding family will be unscathed.”

“The chaebol chairman is like a god,” he added. “He’s somebody who is untouchable within the company and it’s rare for them to have to take full responsibility for decisions that they’ve made.”

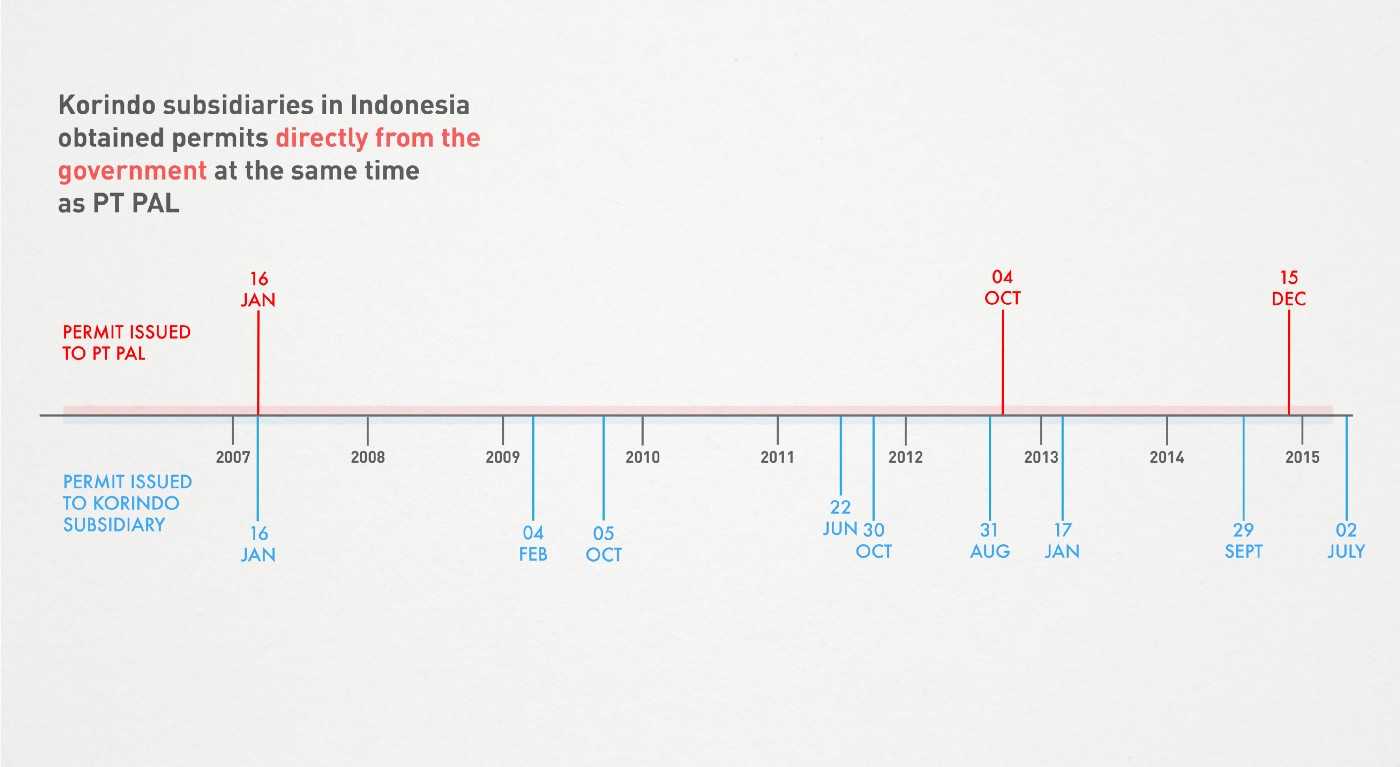

Korindo made liberal use of circular shareholdings when it embarked on its rapid phase of expansion in Papua. It would obtain permits to several plots of land, directly from the government, through three companies it set up in Indonesia. All three were owned by a maze of other companies domiciled in Indonesia, Singapore and the British Virgin Islands.

But for one concession, Korindo did things differently. The exception was PT Papua Agro Lestari (PAL), a company it acquired in 2013 with what it told us was a full set of permits. Korindo said it had taken over PT PAL in a straightforward share deal, from Kim Nam Ku. The true picture, like much of Korindo’s business, appeared to be much more complex.

Part 3: The deal

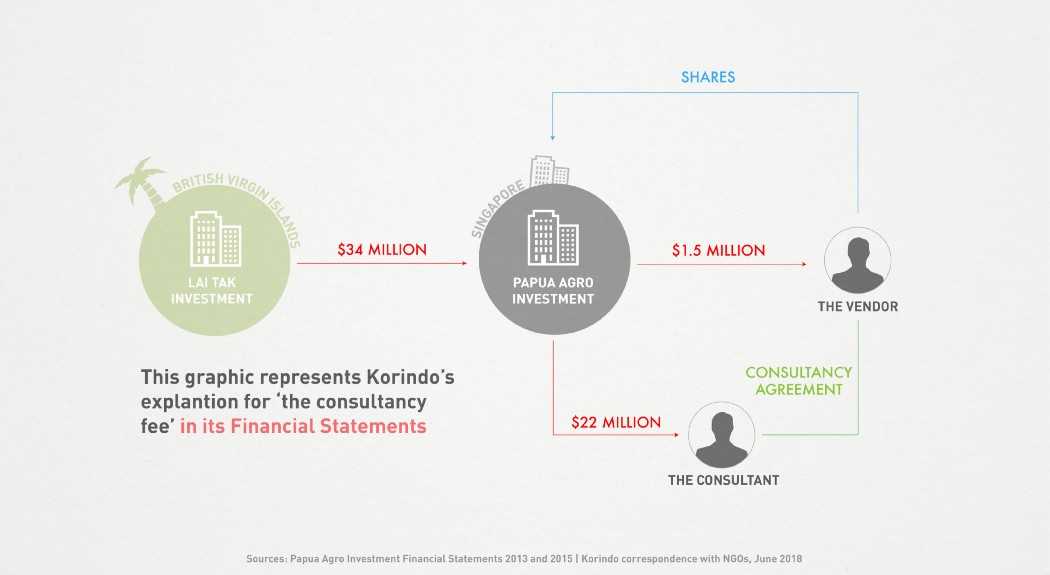

Korindo’s public filings in Singapore give one account of how it acquired PT PAL. In March 2013, the Seungs set up a shell company in the city-state named Papua Agro Investments Pte Ltd (PAI). Eun-ho’s son Robert was listed as a director. Later that year, using a cash investment from one of the group’s companies in the British Virgin Islands, PAI paid $1.5 million for a majority stake in PT PAL, which held some of the permits it would need to transform some 32,000 hectares of primary rainforest into an oil palm plantation.

That same year, PAI paid a further $21.4 million as a “consultancy fee.” According to its financial statements, the payment went to an “expert in getting the plantation rights and projects’ development.” An additional instalment of $500,000 was paid in 2015, for the same purpose, taking the total to nearly $22 million.

In 2018, two NGOs from Indonesia and the U.S. investigated Korindo’s finances and came across the anomalous consultancy payments. They wrote to Korindo as they prepared to publish a report on alleged environmental and human rights abuses driven by its operations. Noting that there were “no official costs to ‘getting plantation rights’ in Indonesia,” they asked what the consultant had done to merit such an enormous fee.

In response, Korindo wrote that the deal had been structured this way at the request of the “share seller” of PT PAL, who had his own “obligations” with the consultant. Korindo said it viewed the total cost of the company, including the consultancy fee, as a fair reflection of its value and had agreed to pay it as part of the deal. “PAI had no obligation to investigate the details of the rights and obligations between the seller and consultant,” Korindo wrote, referring to its Singaporean subsidiary. “Insofar as such payment is legal and does not harm anyone’s rights, PAI feels it was acceptable to make the total payment in the manner requested by the seller.”

Large companies frequently hire consultants for legitimate ends, particularly when investing in unfamiliar markets. But “consultants” also make a routine appearance in major bribery cases around the world.

Last year, for example, Swedish telecoms giant Ericsson was charged by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission “with engaging in a large-scale bribery scheme involving the use of sham consultants to secretly funnel money to government officials in multiple countries,” including Indonesia. Ericsson agreed to pay the U.S. authorities more than $1 billion in fines.

“There are certainly plenty of bribery cases where a ‘consultant’ has been, in the end, a euphemism used in the accounting for an intermediary or a bagman for corrupt officials,” said Bruce Searby, the former Department of Justice prosecutor. “Frankly, this is an old school way of phrasing it, originating in times and places where there was a culture of impunity, making it unnecessary to be too creative about what you called them.”

For the anti-corruption experts who reviewed the payment at our request, the size of the fee jumped out as a red flag. Implausibly large contracts, with millions of dollars spent on seemingly routine or even illogical services, are a frequent feature of corruption cases involving sham consultants. “When you have unexplained consultancy payments, then you have to wonder what things besides the expertise are being paid for,” Searby said.

In its financial statements, Korindo said it was paying for expertise in acquiring land rights. But by the time the payment was made, the conglomerate had already built up decades of its own expertise. During the same period in which PT PAL got permits, Korindo obtained the same kinds of permits for three of its own subsidiaries, for four plantation projects in southern Papua.

Debra LaPrevotte, a former special agent with the FBI who investigated multi-million-dollar transnational corruption schemes involving countries like Ukraine, Nigeria and Bangladesh, said Korindo’s track record of getting permits on its own raised further questions. “It’s a deviation from the norm,” she said of the consultancy payment. “If they got these other permits previously without having to use a consultant? Why did they have to pay $22 million for a consultant this time?” She added, “It seems an astronomical amount.”

The risks that a large fee could be diverted to paying bribes in Indonesia’s natural resource sector were particularly apparent. Investigations by Indonesia’s anti-corruption agency, known as the KPK, have documented bribery at every level of the licensing process. In one example, a billionaire tycoon was caught in a 2012 wiretap investigation arranging bribes for the head of Buol district, on the island of Sulawesi, to issue permits for her palm oil company.

A 2015 survey by the KPK found that almost half of the candidates in that year’s regional elections had been offered illicit campaign finance from businessmen, in return for permits and other rewards if they won. “If you’re dealing with that kind of environment, you know the risk is already there,” said Richard Bistrong, the CEO of Front-line Anti-Bribery LLC, which advises companies on avoiding corruption.

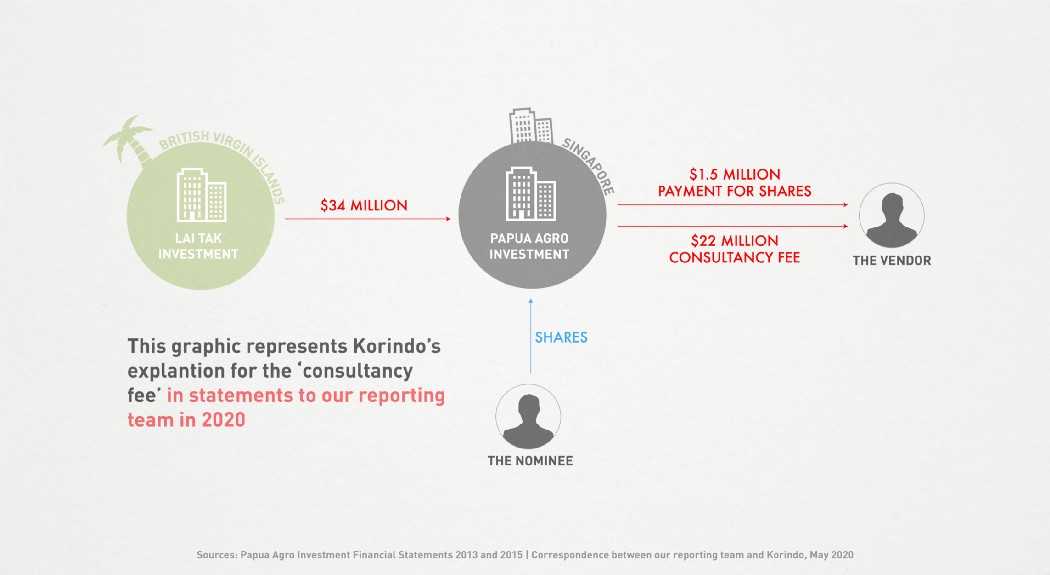

This year, however, when we asked Korindo what the $22 million payment had been for, its account appeared to change. It said the money had not gone to a consultant at all, but to the “de facto owner” of PT PAL at the time of its acquisition by Korindo, a man named Kim Nam Ku, as payment for his shares.

In other words, the “consultancy fee” wasn’t a consultancy fee. In a letter on May 9, Korindo Group managing director Seo Jeongsik described it as a “straightforward share purchase transaction” paid at the market rate. Kim, he said, had earned the money they had paid him by taking PT PAL through a “lengthy and complex regulatory process.”

Why would Korindo misrepresent to the Singaporean authorities a payment for shares as a “consultancy fee” in its financial statements? According to Seo, it was because Kim had wanted to, “for reasons which only he could explain.” Korindo, Seo said, “had no interest in how the transaction was characterised as the payment was made.”

Korindo’s apparent disinterest in how the payment had been characterised raised more questions. A Singaporean lawyer we asked to review the payment pointed out that under the city-state’s Companies Act, knowingly making or authorising a “false or misleading statement” in audited accounts is an offence, punishable by up to two years in prison. As a director of PAI, Robert Seung could be liable. In a letter on 20 May, Seo denied that Korindo or Robert Seung had broken the law.

There was another curious aspect about the new explanation. Korindo told us it had bought PT PAL from Kim, but at the time the payment was made, Kim held no shares in the firm. Corporate records show that Kim’s equity in the company had been transferred to a Seoul-born man named Seo Haeng Won in 2009.

According to the corporate records, Seo Haeng Wong’s registered address was a unit in an upscale apartment complex in Jakarta. Seung Eun-ho, his son Robert, and more than a dozen other individuals listed as directors in Korindo companies also used addresses in the complex. At least one of Seo Haeng Won’s neighbours in the complex had been used by Seung Eun-ho as a nominee shareholder (the full names of other nominees were redacted in the court judgement in Seung’s tax case).

Trawling through records for other Korindo companies, we found that Seo Haeng Won had briefly appeared as a board member in three other Korindo companies in the years leading up to the PT PAL deal. Given Seung’s established pattern of using nominee shareholders, it seemed possible that Seo was just a front, holding shares in PT PAL for Korindo four years before Korindo claimed to have bought the firm.

The theory was supported by a change in PT PAL’s board of directors. On the same day that Seo took over Kim’s shares, in 2009, Kim was replaced as director of the company by a man named Eugenius Simon Lestuny, another longtime Korindo director. Media reports suggested he had had an actual role in running Korindo’s logging operations in Papua since the early 2000s.

When we asked Korindo about Seo Haeng Won’s role in the deal, it said he was a nominee — but for Kim Nam Ku, not Korindo. Korindo told us that Kim had asked Seo to hold his shares on paper. Korindo didn’t explain why Kim might have done this. But it did say Seo had played no role in the deal, which was cut between Kim and Korindo. Korindo declined to comment on follow-up questions about Eugenius Lestuny. Neither Seo nor Lestuny could be reached for comment.

Unpacking the PT PAL deal was like stumbling through a hall of mirrors. The “consultant” was not a consultant; the “share seller” didn’t really own the shares. The nominee was a front for Kim Nam Ku, but he had worked for Korindo. The conglomerate’s explanations seemed contradictory: had the vendor arranged the consultancy fee with the consultant, as Korindo told the NGOs? Or were the consultant and the vendor one and the same, as Korindo told us?

Wherever the truth lay, it was clear that in Korindo’s version of events, Kim Nam Ku had created an asset worth millions of dollars by obtaining permits from government officials. To do so, he would have had to navigate a minefield of corruption risks. The same year PT PAL secured a permit from the Ministry of Forestry, in 2012, the ministry was considered the nation’s most corrupt institution, according to a KPK survey. In 2016, Johanes Gluba Gebze, who had signed permits for PT PAL as the elected leader of Merauke, the district in southern Papua where the company was seeking to operate, was convicted of misappropriating hundreds of thousands of dollars from the district budget.

“You’re not selectively corrupt,” Shruti Shah, the president and CEO of the Coalition for Integrity, a U.S.-based non-profit that fights corruption, said in an interview. “If you have a history of being corrupt in an area like this, it raises the stakes even more.”

So, who was Kim Nam Ku? And what had he been doing in Indonesia?

Part 4: The consultant

Nikolaus Mahuze first met Kim Nam Ku in the mid-2000s, when Kim turned up in Muting, in the northeast of Merauke. A wiry man from Seoul in his late 40s, Kim had arrived with district officials who were guiding investors seeking land to develop plantations. He may have looked out of place in the interior of Papua. But he had already spent around 15 years in Indonesia and was fluent in the national language.

Nikolaus, then around 30 years old, was an agricultural graduate active in his local church. His clan’s ancestral territory lay in the area coveted by Kim and other investors. Nikolaus told us he had acted as a “coordinator”, making sure investors who arrived were meeting with the clans who owned the land they were targeting. Kim quickly pegged him as someone who could guide him through the challenging cultural landscape of the Papuan interior. They bonded over their shared Christian religion. Over the next decade, their friendship would take them from tribal ceremonies in Merauke to shopping malls in Jakarta. “We have the same heart,” Nikolaus said. “He was like a brother.”

Johanes Gluba Gebze, who served as district chief from 2000 to 2010, held ambitions to turn Merauke into the centre of rice production in eastern Indonesia. His vision would soon be turbocharged by President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, who began promoting plans to transform the district’s rainforests and savannahs into a string of giant plantations to produce food and biofuels.

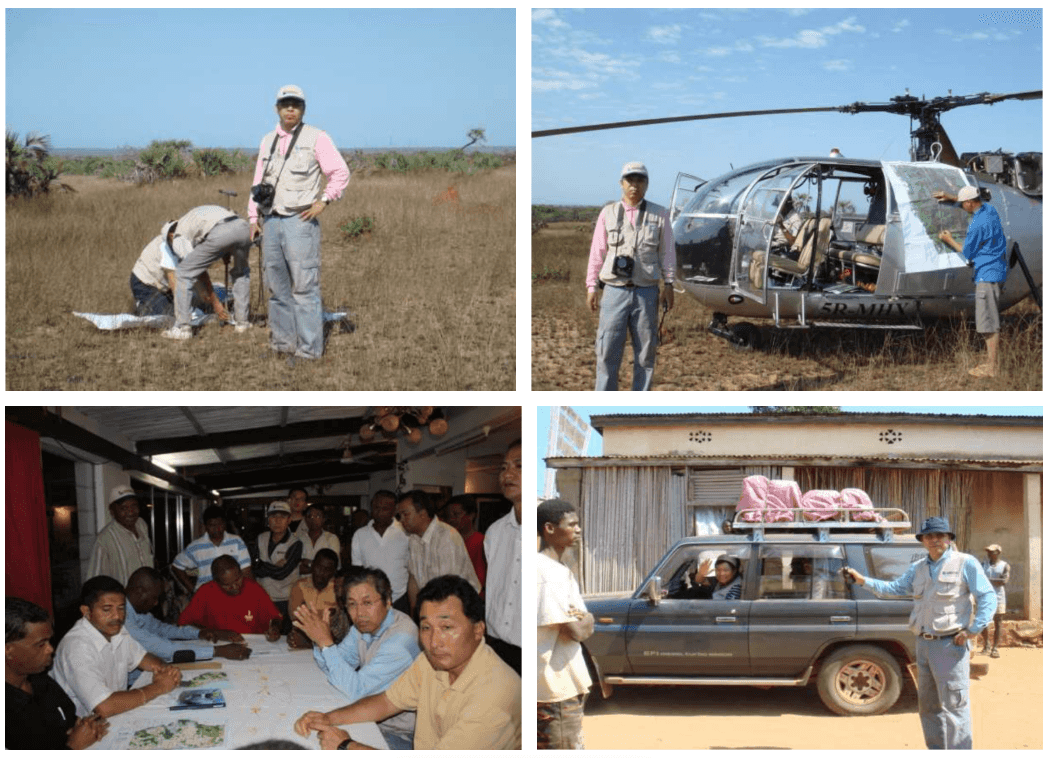

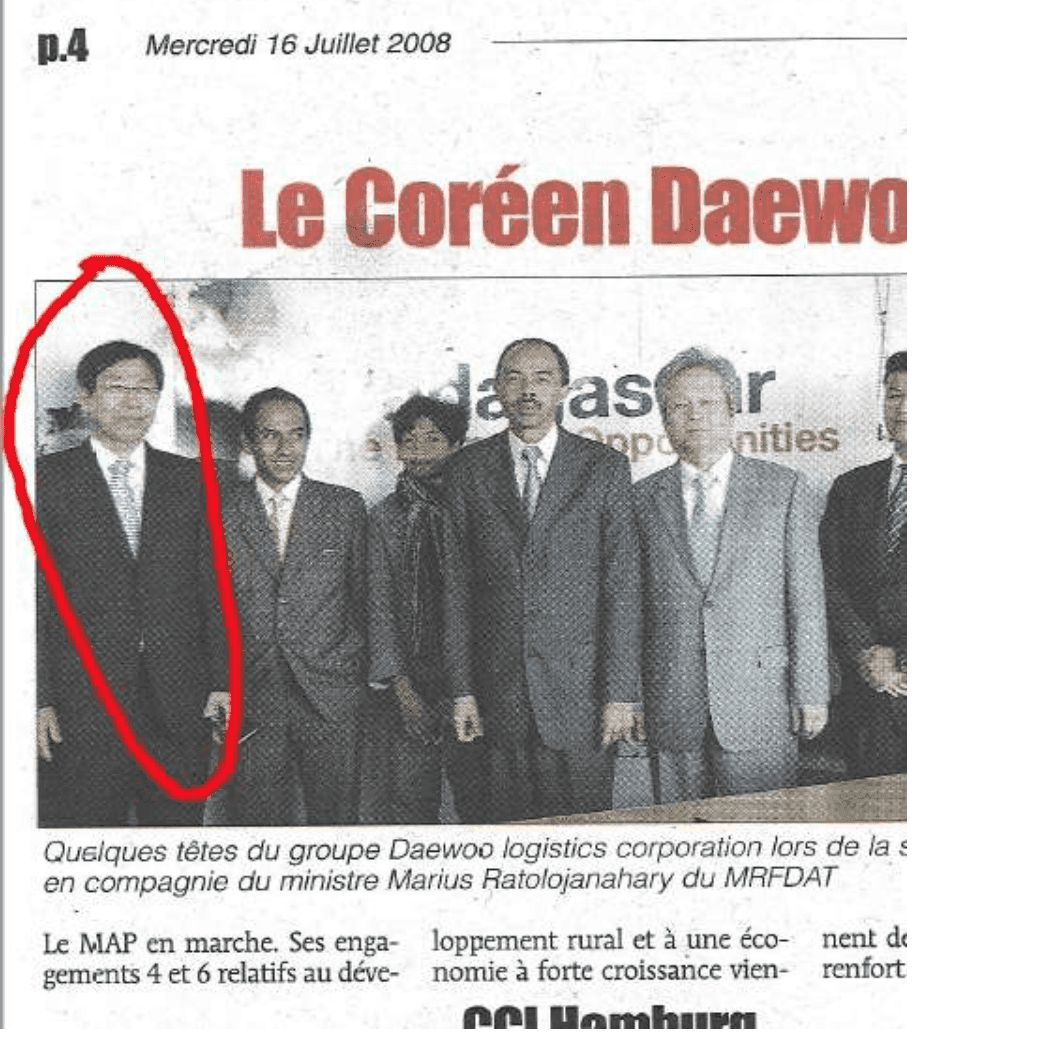

In the mid-2000s, Kim served as a director of the Indonesia branch of Daewoo Logistics, another director at the Seoul-based company told us. A spin-off of the Daewoo Group, a South Korean firm that went bankrupt in the Asian financial crisis of 1999, Daewoo Logistics was buying corn to import to South Korea. In Indonesia, the firm was looking for land so it could grow its own crops, the director said.

Halfway across the world, in the African island nation of Madagascar, Kim’s role at Daewoo Logistics would place him at the centre of what would go down as one of the most controversial agribusiness projects in the late 2000s. It was a crowded field, as soaring food commodity prices sent investors and speculators on the hunt for farmland, and the term “land grab” attracted growing global attention. The government of Madagascar offered Daewoo Logistics 2 million hectares — an area the size of New Jersey, the director said, and Kim’s job was to find out how much was suitable for agriculture.

Kim led a team of some 60 people, including technicians brought with him from Indonesia. Photos we obtained from another source show him travelling across the country by four-wheel-drive and helicopter, examining the soil and meeting with regional officials. After six months spent surveying the land, Kim prepared an investment plan, the director said, that was submitted to the Madagascar government.

In July 2008, Kim appeared on the front page of a newspaper in Madagascar, standing with a government minister and the CEO of Daewoo Logistics. Four months later, the Financial Times broke the news that Daewoo Logistics would lease 1.3 million hectares of farmland, around a third of Madagascar’s arable land, from the state for 99 years. Popular resentment against the deal fanned unrest that forced then-President Marc Ravalomanana to resign the following year, sounding a death knell for the company’s grand visions in Madagascar. In mid-2009, Daewoo Logistics filed for bankruptcy, citing the cancelled project as a reason it failed to weather the global financial crisis then underway.

Back in Papua, Kim was travelling to remote villages, aided by Nikolaus Mahuze, who helped explain the investors’ plans to the clans. Kim also brought Nikolaus along to meetings with government officials in Merauke town, the district capital, including with the local forestry agency and with Gebze, the district chief.

Kim told Nikolaus he wasn’t afraid that he wouldn’t get permits from the government. He was afraid the Papuans wouldn’t accept his project. “I told him, you’re a Christian. If you’re honest, the people will accept you,” Nikolaus recalled. “But if you’re selfish, they’ll reject you.”

In 2006, Kim set up PT PAL and another company, PT Bio Inti Agrindo (BIA), that would serve as vehicles to acquire plantation permits. He was the majority shareholder in both. According to corporate records, BIA was registered to Daewoo Logistics’ address in Jakarta, while PAL was registered to Kim’s home address in the city. Each company received an initial permit from Gebze on January 16, 2007.

On the same day, Gebze also issued plantation permits to two Korindo subsidiaries. Photos we obtained that appear to be dated around this time show Kim, Gebze and a Korindo director named Kim Hoon sitting together in the lobby of a luxury hotel. In one, Kim Nam Ku smiles at the camera, as Gebze signs documents behind him.

When our reporters traveled to Papua last year, Gebze was at large in Merauke town, despite being sentenced to 10 years in prison in 2016 after his conviction by the Supreme Court in the corruption case. He had used the money, siphoned from the district budget, to buy crocodile-skin bags, wallets, belts and luggage made by local craftspeople, to hand out to visiting politicians and businesspeople, in line with a Melanesian cultural norm in which “big men” consolidate power through acts of generosity.

When we reached Gebze by phone, he refused to be drawn on his interactions with investors. He played down his administration’s role in greenlighting the plantations, saying that decisions had ultimately been taken by Jakarta. “Stop pointing and looking for a scapegoat,” he said. “We were not the root of the problem. We only translated the policy [from the central government].” When we brought up the consultancy payment, he said he had never heard of it.

The permit from Gebze was only the first step in a licensing process that required approval from different levels of government. In 2012, Zulkifli Hasan, the forestry minister, rezoned the land in PT PAL’s concession for agriculture. In December the following year, Gebze’s successor as district chief, Romanus Mbaraka, extended the permit issued by Gebze. Neither Romanus nor Zulkifli responded to a request for comment.

Seo Jeongsik, the Korindo managing director, told us that by the time Korindo acquired PT PAL, “the permit process had already been completed.” We obtained a partial record of PT PAL’s environmental impact assessment, a crucial step in the licensing process. This showed it was only completed in 2014, a year after Korindo says it took over the company with a full set of permits.

In April, after months of trying to track down Kim Nam Ku, we reached him by phone. He told us he had lived in Indonesia for three decades and become a naturalised citizen. He presented himself as an independent entrepreneur who had set up his own projects. “I wanted to do business for myself to live in Indonesia, but felt I didn’t have enough capability,” he said. “So I decided to do business with big companies and eventually developed the lands.”

“I was involved in the initial contract, but soon it went out of my hands.”

In September 2011, two years after Daewoo Logistics filed for bankruptcy, Kim sold an 85% stake in the other company he had formed, PT Bio Inti Agrindo, to another South Korean conglomerate, the POSCO Group, for $10 million, according to a contract we obtained. Kim retained a minor stake in PT BIA, and he told us he was still involved as an adviser. But he said he had had nothing to do with PT PAL after selling it to Korindo.

“I was involved in the initial contract, but soon it went out of my hands,” he said. “So I’m unable to say what happened next.”

When asked about the $22 million payment, Kim became evasive. Had he requested that it be paid in the form of a consultancy fee? “Ask the company,” he said, referring to Korindo. Had the money ended up in the hands of bureaucrats or politicians? “I don’t know,” he replied. “I have no idea.” When asked about Seo Haeng Won, the man to whom he had transferred his shares in 2009, Kim said he didn’t know who he was.

Key questions about Korindo’s account of its deal with Kim come down to the timeline. In Korindo’s version of events, it bought PT PAL from him in 2013 with a full set of permits. The permit records tell a slightly different story, that a key part of the process was only completed in 2014.

But a more critical question is whether Korindo took control of PT PAL much earlier than it says. For its account to check out, Kim would have had to appoint one Korindo man whom he claimed not to know, Seo Haeng Won, as a nominee and another, Eugenius Simon Lestuny, as a director. It is not inconceivable, but the more logical explanation may be that both Seo and Lestuny represented Korindo, a company they had been connected with for years, and that Korindo therefore took a controlling interest in PT PAL in 2009. If so, this would indicate that the $22 million, paid out in two instalments in 2013 and 2015, was not a “straightforward share purchase” as Korindo now says.

In a written statement, Korindo insisted it “had not controlled PAL in any ways before the acquisition in 2013.” Kim, after our first phone call, ignored subsequent attempts to reach him, including an extensive list of questions sent to him in writing.

Besides obtaining permits from the state, plantation companies must also convince indigenous communities to sign away their tribal lands. We confirmed that Kim presided over this process for PT Bio Inti Agrindo, before he sold most of his shares in the firm to POSCO. Negotiations with the clans were led by PT BIA’s senior manager, an Indonesian named Yanto Dawenan, who arranged to pay them as little as $6 per hectare in exchange for their lands. (Yanto declined an interview request.) The company’s agreement with two clans, signed in December 2010, was sealed with payments made that month and in July 2011, totalling $12,000 for each clan, and cemented in a traditional pig-sacrifice ceremony. Kim took the bottom half of the pig skull; the Papuans kept the top. We found no evidence Kim had arranged payments to local communities on behalf of PT PAL.

In a written statement, POSCO said that a due diligence review it conducted before buying PT BIA turned up no legal problems with the permits, which had been acquired by Kim, or disputes with local communities. It said that PT BIA had “lawfully” compensated communities in accordance with customary laws. POSCO confirmed that Kim had stayed on as an adviser, but it said he was no longer authorised to represent PT BIA.

In 2013, the same year the first instalment of the consultancy payment was made, Kim invited his old friend Nikolaus Mahuze to Jakarta. Nikolaus was by now a member of the Merauke parliament, nearing the end of his term. Kim wanted to tap him up for a job liaising between PT BIA and Papuan clans. Some of them believed their land had been sold to PT BIA by others staking fake claims, while others were demanding more in compensation.

“Well, I guess this means you’re prosperous now.”

Nikolaus would later sour on his friend, as palm oil factories, he said, started pumping waste into the Bian River. But for now he enjoyed the glow of Kim’s success. Nikolaus was picked up at the airport in Jakarta and driven straight to PT BIA’s office high in the Indonesia Stock Exchange building. Inside, the halved pig skull sat in a box. Photo albums kept under a coffee table documented Kim’s adventures in Papua. Kim took his friend to a shopping mall and bought him gifts: new shoes, batik shirts, a Canon camera, a book about investment. Nikolaus observed that Kim had put on weight, a far cry from the skinny man he had met a decade before. Kim told him he had been stressed by years of trying to secure permits.

“Well,” Nikolaus told him, “I guess this means you’re prosperous now.”

Part 5: The Papuans

The coastal town of Merauke is linked to the interior of the district by the Trans-Papua Highway, a road that winds thousands of kilometers through the Indonesian half of New Guinea. Close to the coast lies a tapestry of savannas and eucalyptus forests redolent of northern Australia. Further north, they give way to swamps and then, finally, to rich tropical rainforests.

Military posts punctuate the lowlands on the approach to Muting village with increasing frequency — one every 20 minutes, then every 10 minutes, then every five minutes. The village lies at the heart of the region targeted by agribusinesses more than a decade ago. Muting, and the string of other hamlets around it, are now ringed to the south and east by oil palm plantations. To the north lie the giant farms run by Korindo and POSCO. All of it once belonged to the clans, numbering thousands of people, that populate the hamlets, whose ancestral territories stretch deep into the plantations.

To reach Muting, we turned off the two-lane highway onto a dirt road, and drove over rickety bridges that seemed liable to break under the weight of our car. When we arrived, the local subdistrict office felt abandoned. An excavator stood in the front yard. We had come here to find out what had unfolded in the years since Korindo began its plantation expansion in the Papuan rainforest.

The village’s main road was lined with homes and stores owned by migrants from elsewhere in Indonesia. Most Papuans lived closer to the swamps, where they could fish and harvest sago starch, a staple of the local diet. In a small, simple house surrounded by sago trees on the banks of a dried-out riverbed, we found Gabriel Wauk, in his late 50s, the head of the Marind tribe in Muting, and Laurensius Omba, in his late 80s, an elder of the Mandobo tribe.

The two men told us that when the South Korean investors arrived, many locals were optimistic that the plantations would improve their lives. Korindo made a string of alluring promises to convince them to give up their tribal lands. The Papuan clans would receive cash for the lands and trees, as well as housing and education. They would even be given their own oil palm smallholdings. Korindo promised to assume many of the burdens of the state, building infrastructure and health clinics and providing electricity.

“It felt like money was growing on trees,” Gabriel told us, as cows and dogs milled around outside. “And now? We eat dirt. We beg in front of their office.”

It was a common refrain among the people we interviewed near Korindo’s plantations in southern Papua. Korindo, they said, had failed to deliver on its promises. The smallholdings and other sweeteners had not arrived.

Even Nikolaus Mahuze, who had helped Kim Nam Ku, was full of regret. “We trusted them to manage our lands,” he said. “Even though their investment has flourished, we’re suffering. Just look at our income, our rights, our environment.”

According to Korindo’s own figures, the company cleared almost 50,000 hectares of rainforest in southern Papua since 1998, before it succumbed to pressure from environmental NGOs and implemented a moratorium on clearing forests in February 2017. The group’s operations had targeted a landscape identified by the WWF as a global priority for conservation due to its “exceptional biodiversity.” It included hunting grounds used by Papuans to find wild pigs, and sago groves that provided them with their staple starch.

Part of the blame, locals said, lay with the government. Local officials had encouraged the Papuans to accept Korindo, telling them the investors would bring much-needed development. But few Papuans realised they would be signing away their customary lands for at least 35 years, the duration of an oil palm lease, after which it would likely revert to the control of the state.

“The people were like chickens without their mothers,” Leonardus Mahuze, who served as speaker of the Merauke parliament from 2009 to 2014, told us in Merauke town. “The district government should have made sure they understood, so they could think carefully before handing over their lands.”

Some Papuans had had no desire to surrender their ancestral lands to Korindo, no matter the price. But according to Anselmus Amo, a priest from Merauke, they never really had a choice.

“Being marked as OPM can be a prelude to being imprisoned, or tortured or killed by the security forces.”

“Suppose you don’t want to deal with the company at all,” Amo, who heads a human rights group affiliated with the Catholic Church, told us at his office in the district capital. “What then? You’ll be pressured. Labeled ‘anti-development’ and things like that. What people really fear is being labeled OPM.”

The acronym stands for Organisasi Papua Merdeka, the Free Papua Organization, a diffuse independence movement that has simmered since Indonesia annexed the region in the 1960s. In 2008, the U.N. Special Representative on Human Rights Defenders reported that Papuans exposing abuse of authority risked being “labelled as separatists in order to undermine their credibility.” Being marked as OPM can be a prelude to being imprisoned, or tortured or killed by the security forces.

“They didn’t know the land would never be returned to them.”

Amo said the security forces were typically present at meetings between locals and Korindo. “To the people, it served as a symbol that the investors were backed by the state,” he told us. “They didn’t know the land would never be returned to them.” Korindo declined to comment on these allegations.

In most places, Korindo paid the Papuans between $5 and $10 per hectare, to give up their land rights for decades. It also agreed to pay them as little as 12,500 rupiah (around $1) for each cubic meter of timber it harvested from their lands. Korindo could export the same timber for 200 times that after turning it into plywood at its mill in Asiki, a village in southern Papua.

In an interview via video conference in April, Kwangyul Peck, Korindo’s chief sustainability officer, said the compensation rates for the land were fair. “The market dictates the price, not us,” he said. The rates for trees, he noted, were set by the local government. In any case, Korindo had spent millions of dollars more on “social programs.” “When we add schools, school buses, clinics, roads, bridges, chicken farms, vegetable farms, electricity, churches, mosques, job training, inter alia, the compensation for the residents would be much bigger,” he added in an email.

In 2017, due to its clearance of a vast area of rainforest and allegations of human rights abuses, Korindo was the subject of a complaint to the Forestry Stewardship Council, or FSC, the main global organisation for certifying sustainable wood. The FSC had certified a timber plantation, sawmills and a paper manufacturing plant belonging to Korindo, even as it cleared huge areas of rainforest in Papua. A panel of three forestry experts, convened by the FSC, travelled to Merauke to investigate the claims.

In its report to the FSC, the panel acknowledged Korindo’s investments in facilities that benefited the Papuans, most notably an “impressive” hospital built near Korindo’s Asiki mill. But it found that in the 10 years since 2007, the conglomerate had spent no more than $4.8 million on all of its social programs in Papua. During the same period, the panel calculated Korindo had deprived the Papuans of $300 million by underpaying for the timber harvested from their lands.

“The activity of Korindo,” the panel wrote, “sanctioned by the Indonesian government has seen a huge and uncompensated transfer of both Forest Capital and Land Capital from the indigenous Papuan people to whom it belonged to the small group of individual shareholders who control and benefit from Korindo, principally Eun Ho Seung and Robert Seung.”

Peck described the $300 million figure as “pure fantasy” on the grounds that the panel had based its calculations on global market prices. Korindo, he said, actually sold its timber locally and had made a loss on the logging operations as it cleared land for plantations. Peck also sent a budget suggesting that Korindo had spent a further $4.5 million on healthcare between 2016 and 2020.

“The activity of Korindo…has seen a huge and uncompensated transfer of both Forest Capital and Land Capital from the indigenous Papuan people…to the small group of individual shareholders who control and benefit from Korindo, principally Eun Ho Seung and Robert Seung.”

We sought to verify the panel’s figures using data from Korindo, the Indonesian government and other sources. We estimated that from 2000 to 2017, Korindo had exported products worth $320 million using timber harvested from its Papuan plantation concessions. We estimated that customary landowners were paid no more than around 0.5% of that figure for the raw materials. We asked Korindo how much it had paid the Papuans in compensation for timber overall, but it declined to answer.

The panel also found that Korindo had “directly benefited” from the presence of the military, which had the effect of suppressing opposition to the company’s activities and to the amount compensation offered. “This issue is systematic and found across the entirety of the company’s business operations,” it wrote. In a report published last year based on the panel’s findings, the FSC wrote that community members lived under “the threat and in some cases use of violence, in an ongoing atmosphere of intimidation.”

In 2004, the Commission for the Disappeared and Victims of Violence, an Indonesian NGO known as KontraS, published a report alleging that Korindo was making monthly security payments to local military commanders, personnel and battalions in southern Papua. “It is not clear what they have to give the company in return,” KontraS wrote in the report.

Korindo declined to answer questions sent via email about these payments. Peck denied that Korindo had any improper relationship with the military.

“We acquired those lands through legal means and with the agreement with both the Indonesian government and residents, and with proper compensation, with which they’re happy,” Peck said. “Yes, there are those who are not happy with it … but that’s not the view of all people.”

Korindo and its supporters point to employment opportunities created by the plantations. But the FSC panel found that about 90% of the jobs with Korindo had gone to migrants from elsewhere in Indonesia, and that “very few” indigenous Papuans appeared to be in managerial positions.

In Kampung Naga, a settlement within one of Korindo’s estates in the south of Boven Digoel district, we met a Mandobo woman, B. (Her name and others have been redacted.) She said she was only 14 when she dropped out of school and began working on a Korindo plantation a decade ago, collecting palm fruit and spraying fertiliser, after her father passed away. Korindo declined to comment on whether it used child labor on its plantations.

Most months, she said, nearly half of her salary went to pay for food she bought at a cooperative within the estate. We found prices there comparable to those in a high-end grocery store in Jakarta. Sometimes, she would have to make due with little food. “In the morning, if there were no vegetables, I would just eat rice,” she told us in the back room of an empty house, where she felt it was safe to talk to a reporter. “Only rice.”

In the report published last year, the FSC noted that while Korindo’s expenditure on social programmes was “very welcome,” it was “not enough to compensate for the losses and damage” done to the natural resources on which the Papuans had relied, before the plantations arrived. The panel had found that by clearing sago groves and rainforest, Korindo had reduced their food supplies. Some Papuans had gone from being self-sufficient to depending on the company for food handouts. The FSC concluded that Korindo had “almost totally disregarded” the Papuans’ “rights to [an] adequate standard of living and to food.”

At a government clinic in Muting, a nurse gave us a database of health checks carried out on hundreds of children in the district between December 2014 and July 2019. Kingsley Agho, an associate professor in biostatistics at Western Sydney University and an expert in maternal and child health, who analysed the data for us, said it showed almost half of the children exhibited stunting, a sign that they were suffering from chronic hunger.

Agho said the rate was surprisingly high among infants younger than six months who should have been exclusively breastfed, indicating that their mothers didn’t have enough food. “You’d expect it to be low” at that age, he said. “Maybe some mothers don’t have money to buy food, and if you don’t eat well you can’t exclusively breastfeed your baby.” By 2019, nearly two-thirds of the newborns were suffering from chronic hunger. Stunting at that age, Agho added, would lead to high levels of infant mortality. The data showed that at least 12 children who had been suffering from malnutrition died in the period captured.

We found K., the mother of one boy who appeared in the data, in Kindiki, a village near Muting. To reach it, we traveled two hours by boat on a river that locals said was polluted with waste dumped by the palm oil mills operating nearby.

K.’s son was born in 2014, the year PT PAL received the final permits it needed to operate. The boy’s ancestral land now fell within the concession. K., who was 24, told us he had been listless as an infant. “He wouldn’t wake up,” she said, chewing betel nut as she spoke. “He just laid on me, while I breastfed him, for about a year.”

Part 6: Following the money

Ultimately, it would take an investigation by government agencies to determine whether Korindo’s “consultancy fee” had funded bribery. “Of course you don’t have a smoking gun,” said Shruti Shah, the president of the Coalition for Integrity. “But you couldn’t find that unless you had subpoena power, you could access banking records and you could figure out where the money went. That would be impossible unless you were a government investigator.”

Not long before last year’s Interpol conference in Singapore, the payment was brought onto the radar of law enforcement in Indonesia. TuK, one of the NGOs that had come across the payment buried in Korindo’s financial statements, reported it to Indonesia’s anti-graft agency, the KPK. In an interview later that year, Laode Syarif, then deputy head of the KPK, declined to tell us whether it had opened an investigation into Korindo or to comment on the payment itself, citing agency policy. (Earlier this month, we again asked the KPK, now under new leadership, if it had ever investigated the payment, and sent similar queries to Indonesia’s National Police and Attorney General’s Office. None responded.)

The KPK has expansive investigative powers within Indonesia, and its sister agency, the Financial Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre, known as the PPATK, can examine bank records domestically. But if it wanted to trace the payment from its source, it would face an obvious challenge: the payment may never have entered the Indonesian financial system. This could place it beyond the immediate reach of the PPATK.

The Indonesian agencies could ask their counterparts in other countries, through which the payment seems almost certain to have travelled, to access the bank records. But to merit such a request, the KPK would first have to do a measure of legwork on its own to develop the case. Putri Rahayu Wijayanti, who specialises in international cooperation at the KPK, told us the agency would have to be at the stage of formally launching an investigation before seeking bank records through Singapore.

Until recently, the law governing the KPK barred it from dropping a case once it had opened a formal investigation, which inhibited investigators from taking that step before the evidence was clear. This presented the agency with a catch-22: it could not seek bank records abroad, which might provide evidence of a bribe, unless it had compelling evidence that a bribe had likely been paid. (A revised version of the law, passed last September, allows the agency to close a case that has been open for two years.)

Theoretically, authorities in Singapore could launch their own investigation. Though the state has no laws specifically prohibiting the bribery of foreign officials, experts we interviewed said a payment made from a Singapore-based company could fall under the jurisdiction of its anti-corruption laws. However, Singapore’s track record on tackling corruption in the financial sector makes it unlikely it would be proactive in looking into the payment.

Though Singapore has a reputation as a clean place to do business — an “oasis of calm” in a corrupt, often-unstable region, in the words of one compliance expert we interviewed there — it is also believed to be awash in illicit cash and assets from abroad. Like Switzerland before it, Singapore has used tight bank secrecy laws to fashion itself into a popular destination for those looking to engage in dubious deals. Its success, Morgan Stanley’s chief economist in Asia once wrote, “came mostly from being the money laundering centre for corrupt Indonesian businessmen and government officials.”

One $22 million transaction would be just “the tip of the iceberg” of suspect money flows in the city state, a Singapore-based lawyer who reviewed details of the payment told us. He said the “consultancy fee” should have triggered a suspicious activity report, an alert to regulators made by the bank that processed it, which can lead to an investigation by the Commercial Affairs Department, an arm of the police that tackles commercial and financial crimes. Singaporean law requires such an alert to be raised for excessively large payments that don’t make obvious economic sense, among other things. Though it’s mandatory for an alert to be made where there are grounds for suspicion, the lawyer said, it would not be uncommon for a bank in Singapore to turn a blind eye.

“Banks get away with a lot,” he told us. If the bank looked the other way, he said, “I wouldn’t be terribly surprised.”

Singapore’s interest is not in policing the world, he added. While the city-state could be expected to pursue a case where the integrity of its own system had been called into question, it would be less likely to take an interest in a payment that simply passed through its borders. “For us,” the lawyer said, “the political interest is not to go where we don’t need to be.”

Putri, the KPK official, noted that the agency’s collaboration with its counterpart in Singapore, the Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau, had improved. The two agencies recently cooperated on a major bribery case involving the airline Garuda Indonesia, in which the beneficial owner of companies in multiple offshore jurisdictions was traced back to Indonesia. “Without international cooperation, that couldn’t be revealed,” said Ariawan Agustiartono, a prosecutor on the case. He added that Singapore had become a more willing partner in cross-border investigations. “Singapore has changed,” he said.

It’s likely Singapore isn’t the only jurisdiction the consultancy payment touched. Because it was made in U.S. dollars, it would have been cleared through the U.S. financial system, potentially bringing the nation’s laws and enforcement agencies into play. “They’ve utilised the U.S. capital markets to make their payment,” said Shah, from the Coalition for Integrity. The U.S. Department of Justice, she added, is “very aggressive in how they interpret jurisdiction.” While Singapore’s approach to policing its financial system is widely viewed to be light-touch, the U.S. authorities have enthusiastically pursued foreign bribery cases, leading to a string of transnational cases being settled in the U.S. Under its Kleptocracy Asset Recovery Initiative, the justice department recently broke open the multibillion-dollar fraud at Malaysian state fund 1MDB, one of the world’s largest ever financial scandals.

U.S. authorities might also be unlikely to initiate an investigation of their own accord, however. Other cases prosecuted under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act have had a firmer U.S. nexus than Korindo’s payment, involving U.S. citizens, companies, stock exchanges, or stolen funds used to buy real estate in places like Manhattan or Florida. The justice department doesn’t suffer from a deficit of corruption cases to choose from. Debra LaPrevotte, the former FBI special agent, was involved in a programme chasing money stolen by kleptocrats, involving the wholesale corrupt looting of states like the Democratic Republic of Congo and Ukraine, in which the stakes ran into the billions of dollars.

But U.S. authorities also have an unparalleled track record in assisting other countries in transnational financial investigations. Searby, the former justice department prosecutor, said U.S. agencies could potentially deploy their power to run down evidence across the world. “The U.S. has laws that apply extraterritorially to events that occurred largely overseas,” he said. “You have well-funded, highly trained experienced enforcement in the U.S., with resources to pursue documents.”

If Indonesia asked for help with the case, through what’s known as a mutual legal assistance treaty, or MLAT, LaPrevotte said, U.S. agencies would likely comply. “Given the information you already have, there’s probable cause to believe that bribes are being paid,” she told us. During LaPrevotte’s time at the FBI, an MLAT request came in from Bangladesh, and “the next thing I knew I was on a flight with my DoJ attorney to Dhaka”. She helped uncover a corruption scam connected to the son of the former prime minister, in which bribes were paid through local “consultants” and money was laundered through Singapore.

Tracking Korindo’s payment, LaPrevotte said, could be relatively straightforward, given what appears to be a “finite group of players” involved, and a single flow of money to follow. If the KPK filed a request to the U.S. agencies, they could subpoena the records in New York, likely finding a small digital trace of a payment that bounced through the system seven years ago, and potentially follow it as it moved on.

“If you’re paying me for consulting fees, then it’s sitting in my bank account for a while,” LaProvette said. “But if it’s being used to facilitate bribes, then the money is moving on to grease the palms of individuals who have power and influence. So if that money does leave that account in dollars again, the U.S. would have the ability to trace some of those outgoing transfers.”

Whether or not that might happen could come down to the decision of an enforcement agency — whether in Indonesia, Singapore or the U.S. — to prioritise an investigation. Shah, Searby and LaPrevotte all said that it did merit investigation, and that the case was more important than the $22 million figure alone might suggest. The much larger revenues that flowed from logging and producing palm oil raised the stakes. So too did impacts that could not be calculated in monetary terms. “You’re not just looking at money when you’re thinking about taking a case,” Shah said. “It’s about what it does to the environment and what it does to the people living there.”

For Searby, any “huge, unexplained consultancy fee” in the palm oil sector merits the attention of law enforcement. “There’s so much at stake for the environment, for the way of life for thousands of vulnerable people, that you have to put a priority on examining situations that arise where there’s large unexplained transfers of wealth going into these sectors,” he said.

Without an investigation, the truth behind the consultancy payment may never become fully clear. There may be legitimate reasons for the structures Korindo has put in place and the way the PT PAL deal was arranged. But while so much of the group’s business remains opaque, its explanations are contradictory and key questions go unanswered, it remains impossible to determine.

This article was produced with the support of the Money Trail Project.

To see other articles plus films and photos from The Gecko Project as they come out, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube. Sign up to our mailing list here.