- Indonesian companies were given until March this year to disclose their “beneficial owners” under a 2018 presidential regulation, but less than 1 percent have complied.

- In the easternmost corner of the country, investors hidden by layers of corporate secrecy continue to bulldoze an intact rainforest and have nearly finished building a giant sawmill.

- The government is drafting new regulations to close loopholes in the rules governing anonymous companies, which could yet open a new front in the fight against deforestation and land grabs.

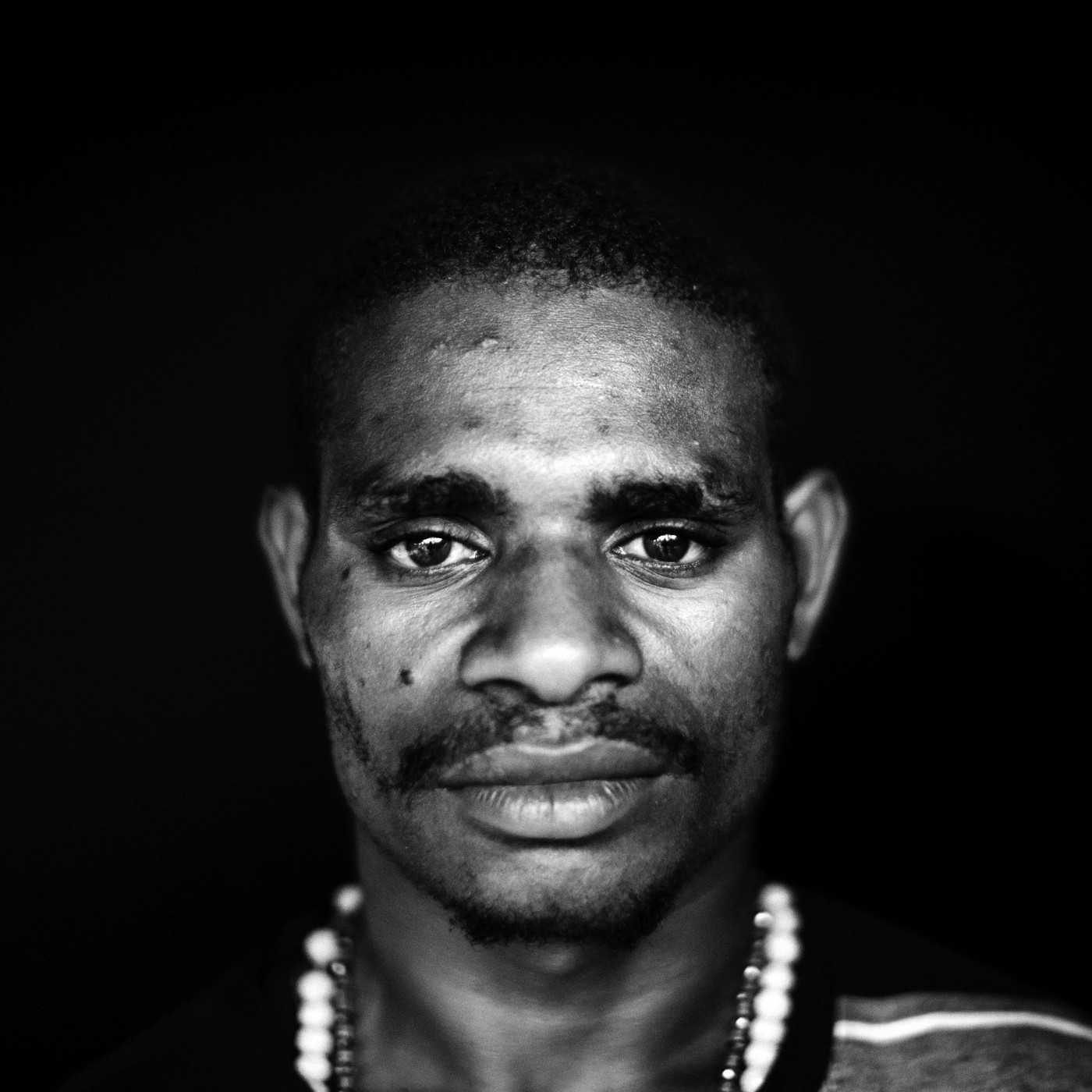

When a string of palm oil companies arrived in the village of Anggai, in a heavily forested corner of Indonesia’s easternmost Papua province, Robertus Meyanggi hoped they would help his community prosper.

Before long, his optimism faded to despair. The promises to build schools and health clinics and provide electricity never materialised, years after the firms, said to be owned by the same conglomerate, set about clearing rainforest to make way for an oil palm plantation.

Meanwhile, villagers’ requests for basic information about the project, such as its size and precise location, were met with stonewalling. Even copies of signed agreements between some clan representatives and the companies were withheld from community members. Soon there were more companies, one constructing a giant sawmill to suck in timber from their land, but no more clarity.

“We don’t even know who owns these companies,” said Robertus, an indigenous Auyu in his mid-20s. “We’re completely in the dark.”

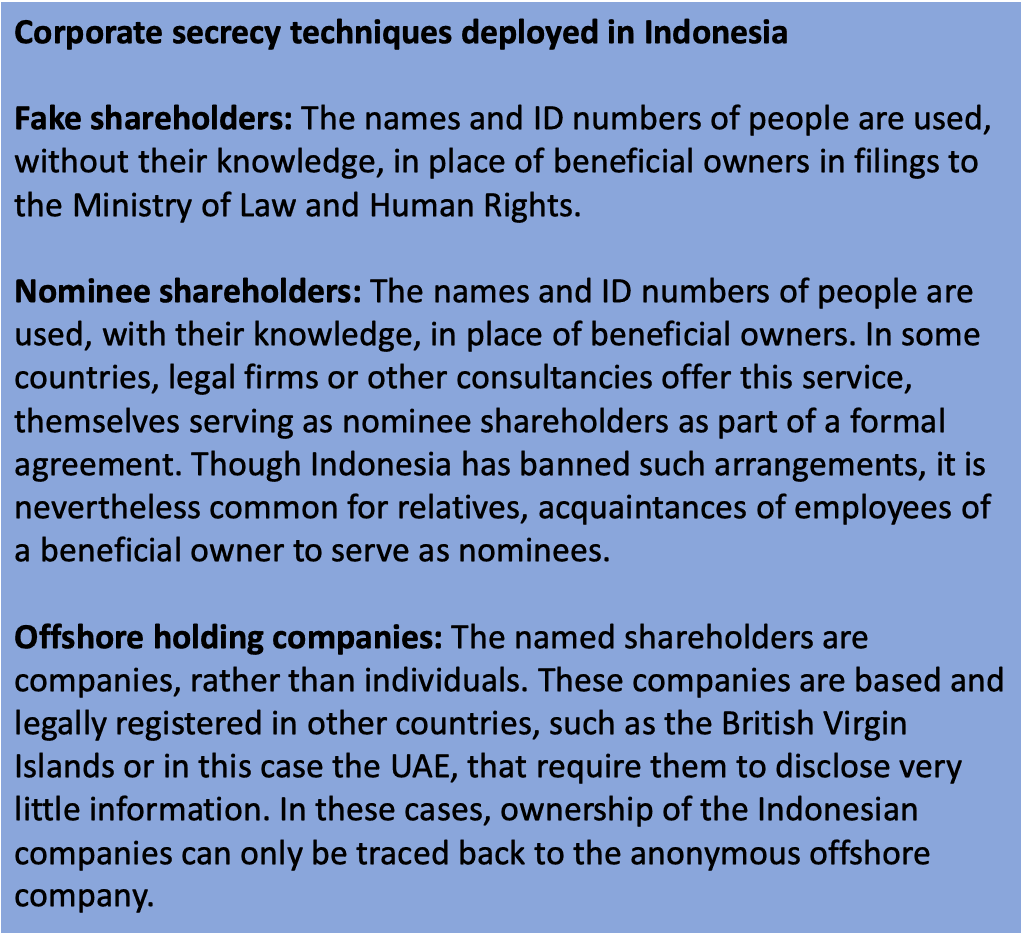

Anggai is one of hundreds, if not thousands, of villages across Indonesia that has become embroiled in a land-rights conflict with a natural resource firm. In many cases, these companies are managed through complex corporate structures that render their true owners impossible to discern.

The companies in Anggai, for example, are owned by holding companies in the United Arab Emirates cities of Dubai and Ras Al Khaimah — two of the world’s secrecy jurisdictions, where regulations are deliberately crafted to enable shareholders to hide their identities. This opacity doesn’t only affect villagers; both the head of Boven Digoel district, in which Anggai is located, and officials at the provincial investment agency have expressed confusion over who is behind the firms.

In other cases, companies are owned on paper by individuals serving as front, or “nominee,” shareholders. Last year, Greenpeace ended its partnership with Sinar Mas after the billionaire-owned conglomerate was allegedly found to have used nominees to disguise its ownership of companies clearing rainforest in Borneo. Sinar Mas has denied the accusation.

In March 2018, Indonesian President Joko Widodo signed a landmark regulation giving companies one year to disclose their true, or “beneficial,” owners to the state.

Sx months after the passage of the deadline, however, Indonesia has made little progress enforcing the new rules, according to officials and informed observers.

Only 7,000 companies, out of more than 1 million registered in Indonesia, filed information by March this year, said Nevey Varida Ariani, who is part of a team at the Ministry of Law and Human Rights tasked with implementing the regulation.

Moreover, many have simply copy-pasted the names listed in the original documents that established the company, she added.

“It seems [the submitted information] is only reaching the first level in accordance with [a company’s] articles of association,” Nevey said in an interview. “We can’t yet see the second and third levels and so on — we haven’t actually got to the real owner.”

The regulation places Indonesia among a growing list of countries attempting to clamp down on the use of anonymous companies, especially due to their role in facilitating money laundering, tax evasion and terrorism financing.

“The Puppet Masters,” a landmark 2015 report by the World Bank, revealed how such entities were routinely featured in cases of high-level corruption, worth cumulatively $50 billion.

In the world’s largest ongoing financial scandal, former Malaysian prime minister Najib Razak is standing trial over his alleged role in the theft of billions of dollars from sovereign wealth fund 1MDB through an international network of fraudulent shell companies.

“Companies are being used in these cases to cloud the eyes of enforcement agencies,” Latheefa Koya, chief commissioner of the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission, said recently in Kuala Lumpur. For Malaysia, she added, “not having strong beneficial ownership legislation is not an option.”

The response to corporate secrecy, like the problem itself, has been transnational. A declaration at the 2013 G20 summit in St Petersburg pledged member countries, including Indonesia, to “tackle the risks raised by opacity of legal persons and legal arrangements.” The U.N. Convention against Corruption, ratified by Indonesia, encourages states to promote beneficial ownership transparency as a means of combating graft.

If successful, these efforts may also have consequences in the forests of Indonesia, where investors driving deforestation remain hidden behind layers of corporate secrecy.

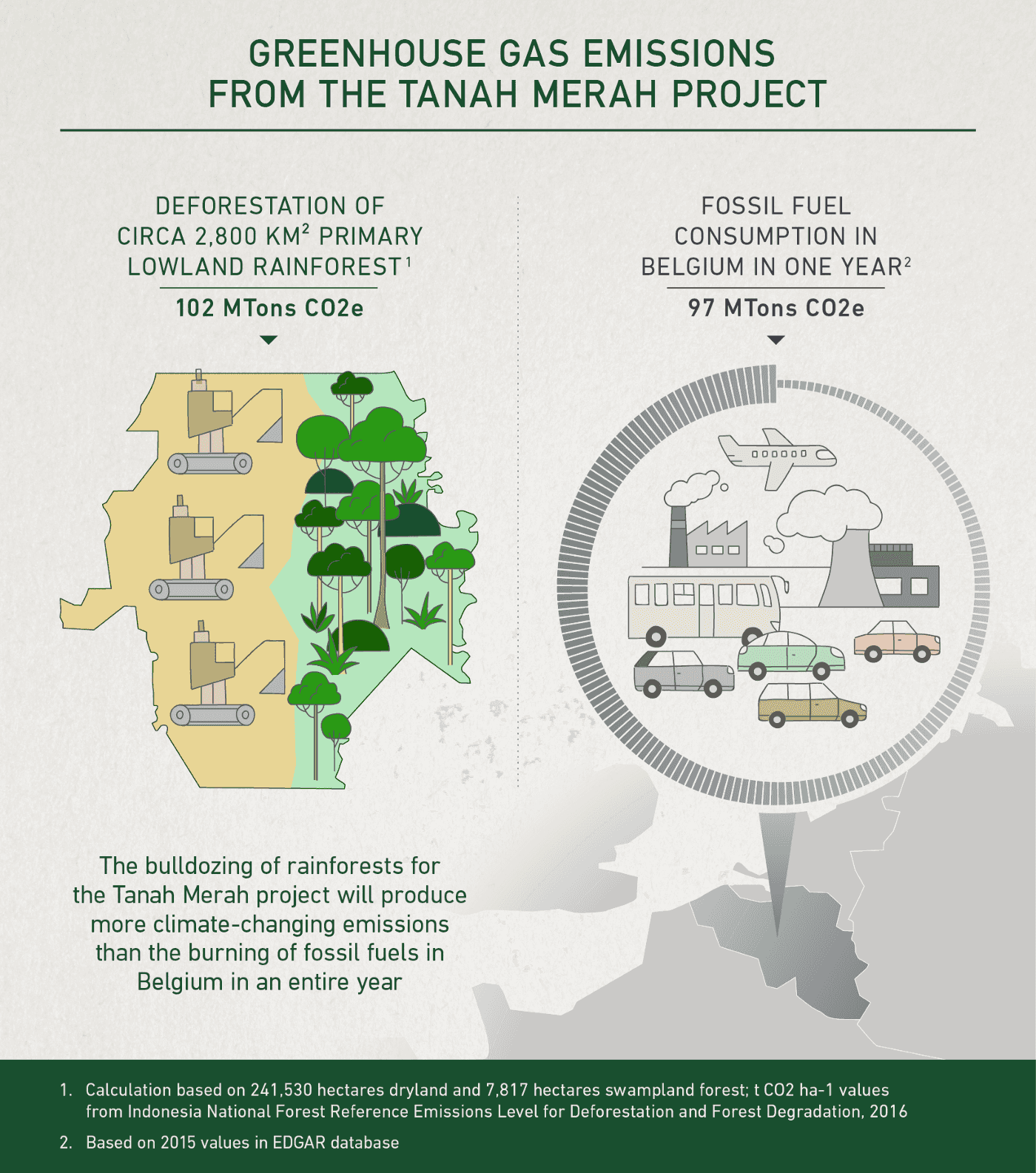

The palm oil companies operating in Anggai are among seven firms that have received permits to create, collectively, the world’s largest oil palm plantation. If the land set aside for the project, located in the heart of Asia’s largest stretch of intact rainforest, is cleared, it will generate as much climate-changing emissions as the burning of fossil fuels in Belgium does in a year.

Last November, an investigation by The Gecko Project, Mongabay, Tempo and Malaysiakini revealed how investors behind the project were hiding behind a dizzying array of corporate secrecy techniques.

Since the seven companies were formed in 2007, their ownership has changed hands several times. The people initially listed as shareholders included low-paid cleaners living in a Jakarta slum who were completely unaware of the project. In 2010, control of all seven firms was transferred via a separate group of mostly nominee shareholders to a little-known company called the Menara Group, run by an Indonesian businessman named Chairul Anhar. Menara eventually sold majority stakes in four of the companies, including those operating in Anggai, to the anonymous firms in the UAE.

Menara sold two of the other companies to Tadmax Resources, a publicly listed logging and property firm in Malaysia. The sale was carried out through a pair of Singapore-incorporated companies that were also owned by nominees. This meant that the $80 million Tadmax paid for the plantation companies could not be traced to its ultimate recipient.

To date, three of the seven companies have cleared 83 square kilometers (32 square miles) of forest, some 3 percent of the total project area.

Construction of the sawmill, intended to process billions of dollars’ worth of timber from clearing the forest, is said to be nearing completion. The mill’s majority owner remains unclear, obscured by an anonymous company in Dubai. The minority owner is the family behind Shin Yang, a major logging firm from Malaysia that has been embroiled in allegations of illegal logging and human rights abuses for years.

Since 2017, a succession of clues have pointed to the Hayel Saeed Anam Group (HSA Group), a conglomerate owned by a wealthy Yemeni family, as the true owner of the four companies sold into the UAE, including the ones clearing forest.

After the sales were made, two members of the Hayel Saeed Anam family and four senior executives in the HSA Group appeared on the boards of the Indonesian companies, corporate records show.

Around the same time, the family’s palm oil trading arm in Malaysia, Pacific Inter-Link (PIL), announced on its website that it was “in advance[d] stages” of acquiring 80 percent stakes in “several Indonesian companies” that collectively held licenses for land covering 1,600 square kilometres (620 square miles). The area and equity matched those of the four companies sold into the UAE.

A proliferation of other clues link the Yemeni family to the Papua project. Another PIL subsidiary advertised for a job overseeing timber harvesting in Boven Digoel, the site of the project. A consultant at a Jakarta auditing firm contracted to certify the legality of timber from the project said his company had been hired by PIL. Tadmax, which has openly invested in the project, announced it was forming a joint venture with PIL and other firms to construct the sawmill. (Tadmax has since sold its stake in the joint venture).

However, PIL has repeatedly denied that either it or the family members ever invested in the project. Its position is that it considered buying the Indonesian firms but ultimately decided not to because the investment was “unviable”.

In its most extensive statement on the matter to date, PIL said that the family members and “certain other individuals” had joined the boards at the request of an unnamed businessman, to “give the project credibility”, but that they neither exercised any control over the companies nor attended any board meetings.

In May 2018, one month after Greenpeace accused the family of controlling the four plantation companies, widespread changes were made to those companies’ boards, with new individuals replacing the family members and most of their known associates.

The new board members include prominent members of the Indonesian establishment. One of them, Tommy Sagiman, is a retired police general who was deputy head of Indonesia’s anti-narcotics agency. Reached over WhatsApp, he told us he had been asked to join the board but never had any active role in the project. He wouldn’t say who had recruited him.

Another, Alwi Shihab, is a former Indonesian minister of foreign affairs now serving as President Joko Widodo’s special envoy to the Middle East. He, too, said he had nothing to do with the project, claiming over WhatsApp to have “resigned a long time ago” from the companies, though his name appears on the firms’ most recent filings to the Ministry of Law and Human Rights.

The new board members also include Bachir Soualhi and Hamidon Bin Abdul Hamid, academics in the Department of Islamic Revealed Knowledge and Human Sciences at International Islamic University Malaysia. Bachir is a former marketing consultant for PIL, according to his LinkedIn profile. Neither could be reached for comment.

Some of the new board members have played a more active role in the firms’ management, representing them in meetings with government officials in Jakarta.

One of them is Arvind Johar, the president director of two of the companies sold into the UAE. He was employed by PIL as recently as August 2018, a receptionist at the firm’s Jakarta office confirmed at the time. He declined to comment when reached by phone.

Mohammed Abdulatef has also represented the UAE-owned firms in meetings with the government.

“I’m sorry, I’m not in a position to reveal any information,” he said when reached by phone, before hastily ending the call.

Though its efforts to date have stalled, the Indonesian government is now redoubling its efforts to compel companies to comply with the new rules on transparency of ownership. The law ministry is drafting an implementing regulation that officials hope will close the two biggest gaps left by President Widodo’s original decree: the absence of defined sanctions against firms that fail to comply, and the lack of a bureaucratic mechanism to verify whether the information submitted is accurate.

The ministry’s current system for recording company shareholders and board members operates as an “essentially passive” filing registry, with limited monitoring of the information provided, according to the Asia/Pacific Group on Money Laundering, an intergovernmental body that reviews countries’ money-laundering enforcement. So without a viable system for checking the accuracy of companies’ submissions, the new policy will be “useless,” said Belinda Sahadati Amri, a legal analyst with Auriga, an NGO that investigates natural resource firms.

The law ministry has consulted with Auriga in its efforts to devise a database of beneficial owners. Belinda expressed concern that the system would be incapable of capturing numerous layers of ownership, or that the ministry would have the resources to dig into the identity of possible nominees. “Actually they can cross-check [the data] if they want to,” she said. “But I don’t know if they’ll have the manpower to do that.”

This challenge is not unique to Indonesia. In 2016, the U.K. government began publishing its own database of beneficial owners. An early analysis of the data by a group of anti-corruption organisations found that almost 3,000 firms had listed their owners as other companies registered in offshore secrecy jurisdictions. This fell outside the rules as it did not reveal the beneficial owners, but it had not been caught by the agency holding the data because it was relying on companies’ self-declarations.

Nonetheless, the U.K. system was upheld by the same organisations as an exemplar of transparency. The information was publicly available in a format that allowed large-scale analysis by journalists and researchers with the intent to verify the information. It remains an open question whether Indonesia’s beneficial ownership data will be publicly available. At present, the names of a company’s direct shareholders and declared board members can be accessed from the law ministry for a fee.

The benefits of transparency are illustrated by a “very unique and very progressive law” recently enacted in Slovakia, said Andrej Leontiev, co-head of the Bratislava office of international law firm Taylor Wessing and one of the authors of the act. Leontiev gave a presentation about the law at a recent workshop on beneficial ownership organised by the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime in Kuala Lumpur, attended by government officials from around Asia.

The Slovak Anti-Shell Companies Law stemmed from a scandal in which thousands of subcontractors went unpaid by a construction firm, Vahostav, which had shifted money to anonymous shell companies in other countries. The law requires any firms doing business with the state to declare their beneficial owners, with the data publicly available, for free, via an online database.

“We shifted the burden of proof to the company. Because we all know it’s nearly impossible to get information from a place like Delaware or some Caribbean island.”

The Slovak law allows anyone to challenge the veracity of a company’s disclosure, in which case the firm must prove before a court that the information provided is accurate. If the company is found to have given false information, it can lose public contracts and its executives can face fines and other penalties.

“Very important — we shifted the burden of proof to the company,” Leonitiev said during his presentation. “Because we all know it’s nearly impossible to get information from a place like Delaware or some Caribbean island. The court can’t get it. So the company, if it ends up in court, has to prove that the registered beneficial owners were truly the beneficial owners at that time.”

Delaware is a notoriously opaque jurisdiction, as are British overseas territories such as the Cayman Islands and the British Virgin Islands.

Herda Helmijaya, the coordinator of Indonesia’s National Strategy on Corruption Prevention, was impressed with the Slovak example. “We have to learn from Slovakia about how they implement the beneficial ownership regime,” he said in his own presentation at the workshop.

A film produced by the Open Government Partnership on Slovakia’s law governing beneficial ownership:

In theory, such a system would provide an ordinary citizen like Robertus, the villager from Anggai, with the means to expose the identity of the investors clearing his ancestral forest. For the time being, he remains — along with almost everyone else — in the dark.

For a while, Robertus worked as a surveyor for one of the palm oil companies in Boven Digoel. In 2017, however, he left the firm to continue his education.

“If no one here understands the law, we will definitely be cheated,” he said, after quitting his job. “My goal is to get a law degree so that I can help us, and others, secure our rights.”

Follow The Gecko Project on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. Sign up to our mailing list here.