- The secret deal to destroy paradise is the third instalment of Indonesia for Sale, an in-depth series on the opaque deals underpinning Indonesia’s deforestation and land-rights crisis.

- The series is the product of 23 months of investigative reporting across the Southeast Asian country, interviewing fixers, middlemen, lawyers and companies involved in land deals, and those most affected by them.

- The secret deal to destroy paradise is the product of a cross-border collaboration between Tempo, Malaysiakini, Mongabay and The Gecko Project.

Prologue: Johor Baru, 2012

In December 2012, at a press conference on the sidelines of an Islamic business forum in Malaysia, a man named Chairul Anhar made a bold claim. His company, he said, held the rights to 4,000 square kilometres of land for oil palm plantations in Indonesia.

If true, it would make Chairul one of the biggest landowners in the country. That land was not just anywhere, but in New Guinea, a giant island that glittered in the eyes of investors. Shared by Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, the island had the world’s biggest gold mine, untapped oil and gas, and the largest remaining tract of pristine rainforest in Asia. For the companies that had steadily logged their way through the rest of Southeast Asia, New Guinea was the last frontier. For the investor who could tame it, a fortune awaited.

Then in his mid-40s, with a stout build, a thin moustache and a buzz cut, Chairul presented himself as such an investor. He claimed to be the president, CEO and owner of a sprawling conglomerate, the Menara Group. He travelled in a Bentley and private jets, and rubbed shoulders with the political elite of Malaysia and his native Indonesia.

The basis of his claim was the Tanah Merah project, a plan to generate billions of dollars by logging untouched rainforests, home to indigenous tribes and a treasure trove of biodiversity, then razing what remained and replacing it with oil palms. If fully developed, it could become the single biggest palm oil plantation in Indonesia. But Chairul’s business, and his connection to the project, was more convoluted than the image he presented.

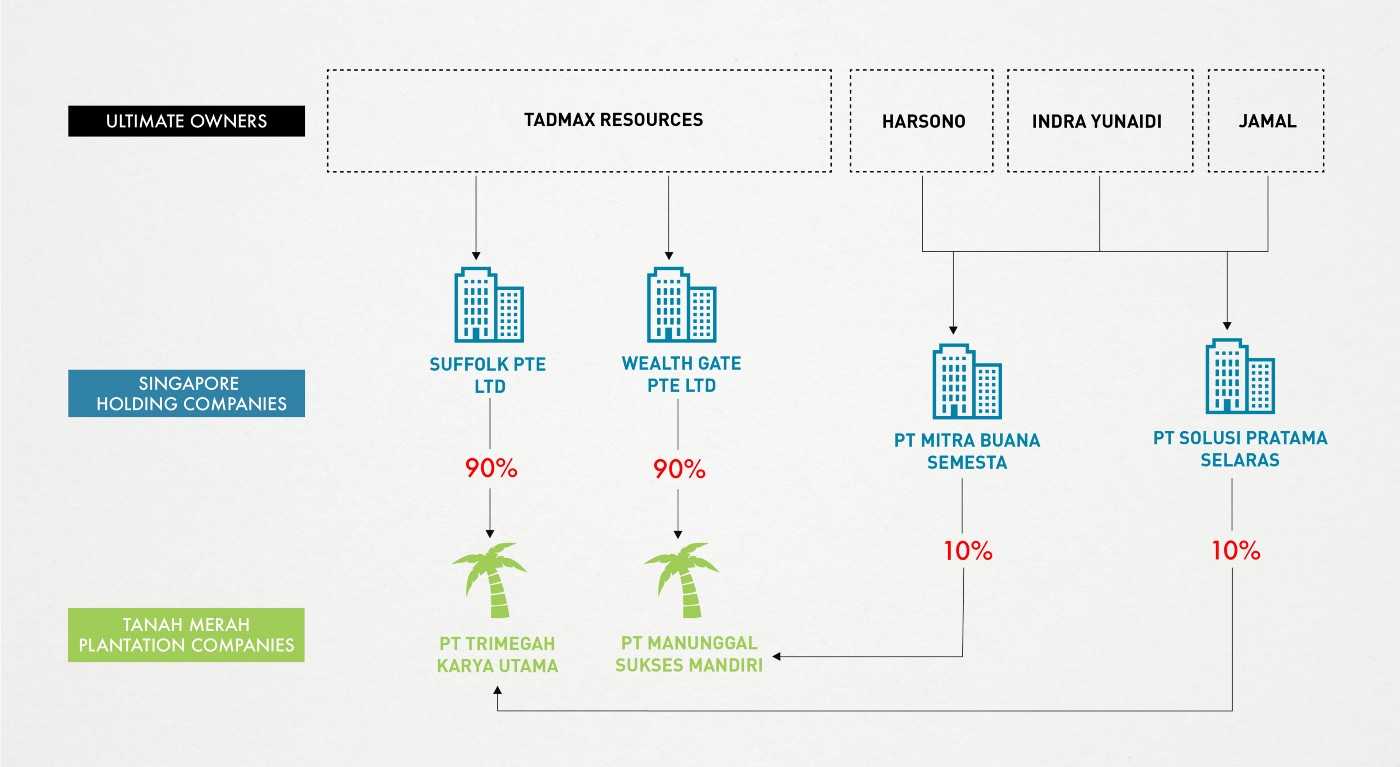

The rights to the land had been acquired through a maze of shell companies. The shareholders were mostly fronts, controlled like puppets on a string. The companies were a façade, masking whoever was truly set to benefit from the project — whether Chairul or someone else.

By the end of 2012, most of the equity in these shell companies — and with them the rights to the project — had been sold to offshore firms based in the Middle East and Singapore. Those sales channelled at least $80 million, likely several times more, back to the web of shareholders connected to Chairul, and brought a varied cast of new actors into the project: a former Indonesian chief of police, a secretive Yemeni family, a notorious logging firm from Borneo, and a conglomerate connected to a major Malaysian corruption scandal.

By the time of the press conference, Chairul had only a slender claim to the land. He was the business Svengali who had brought these other interests together, generated a fortune, and lit the fuse on an environmental disaster that is only now beginning to unfold.

The threat to the rainforests of Indonesia was very real. Since the turn of the century, only Brazil has lost more rainforest than Indonesia. One of the leading causes of this deforestation was a boom in industrial-scale plantations that began in the early 2000s. Those plantations enabled Indonesia to become the leading producer of palm oil, an edible oil used in an endless array of consumer products. But it also sparked an environmental crisis, as the carbon locked up in rainforests was released into the atmosphere.

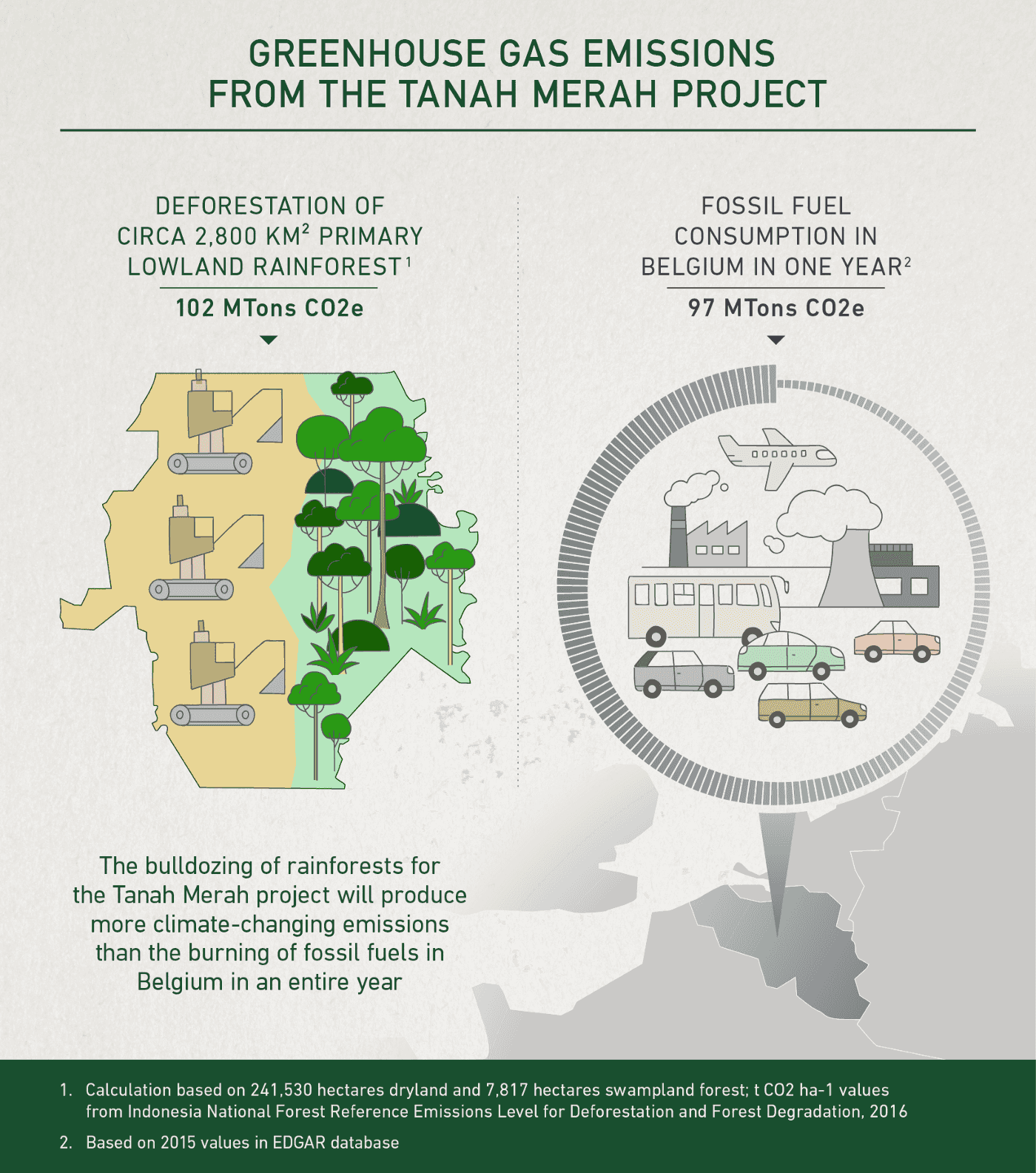

The volume of greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation in Indonesia has made it a matter of international concern. Norway has pledged $1 billion in an attempt to incentivise reforms to curb them. Since 2015, the administration of President Joko Widodo has sought to rein in the plantation industry, most recently by enacting a temporary ban on any new permits for palm plantations. Though just a small proportion of the Tanah Merah project has been developed, the permits were issued before the ban came into force, and the forest remains slated for destruction.

Today, an area larger than Manhattan has been cleared within the Tanah Merah project. This is only a fraction of the total project area. If the rest is bulldozed as planned, it will release more emissions than Belgium produces by burning fossil fuels each year. If the giant sawmill that is today being constructed on the land is completed, it will suck in timber for years to come, settling the fate of swathes of rainforest in southern Papua.

In the decade since the inception of the project, the ways in which the rights to it have been obtained and moved have been shrouded in secrecy. The companies involved have employed all of the tools of corporate secrecy that prevent key questions from being answered. Critical aspects of the permitting process that underpin the entire project are being withheld from public scrutiny. The true owners of the companies clearing the forest today remain hidden.

A cross-border investigation involving news organisations from four countries — The Gecko Project, Mongabay, Tempo and Malaysiakini — attempted to pull back the corporate veil. We sought to find out who had obtained the rights to a project of such magnitude and, perhaps more importantly, how. Our investigation exposes the methods apparently employed to ensure the people who control the fate of these forests — through their money, power and political decisions — have covered their tracks.

Part One: ‘I wasn’t going to issue permits to just anyone’

When Yusak Yaluwo was elected chief of Boven Digoel district in 2005, at the age of 35, he assumed control of a jurisdiction at the heart of a vast stretch of jungle. The district lies in the very eastern corner of Indonesia, in Papua province. “When you fly over the island, still even today, mostly what you see is unbroken expanses of rainforest,” said Dr. Bruce Beehler, a biologist at the Smithsonian Institution, who has spent the last four decades studying the trees and birds of New Guinea.

Across the rest of Southeast Asia, such landscapes have been steadily destroyed over the past half-century. The human activities that drive deforestation tend to work incrementally. First comes logging that fragments and damages the integrity of the forest, bringing roads that act as a conduit for more pressures. The damaged forest becomes prone to fires and, finally, it is clear-cut to be replaced with plantations.

The consequence is that intact or primary forests, which hold the most carbon and support the most wildlife, are increasingly rare. Papua has more of this forest than any other province in Indonesia, with districts like Boven Digoel, among the largest in the country, stretching across 27,000 square kilometres of mostly pristine jungle.

Some of the species that evolved here are iconic, like the brightly coloured birds-of-paradise. The island has high levels of endemism, with species found nowhere else on Earth. Many more species remain unknown to science, yet to be discovered by outsiders, Beehler said. “I can assure you that the forests of the Digul [River basin] are super-rich, and have probably millions of species of invertebrates, micro-organisms, and plants,” he told us. “They may hold in their chemistry all sorts of odds and ends that could be very useful to humankind in the future if we were to get a grip of them.”

The indigenous peoples of New Guinea, composed of clans speaking hundreds of different languages, have lived in close connection to the forest for millennia. Their identity and culture remain deeply bound to the natural world. By the time Yusak took office in 2005, many of the people under his jurisdiction still pursued livelihoods dependent on hunting, gathering fruit and processing starch from the sago palm. These pursuits have had a light impact on the forest.

Perhaps the most transformative power available to a district chief — known in Indonesia as a bupati — is the authority to issue permits for large plantations. Such plantations can bring investment to districts with basic economies and limited budgets. But if not carefully managed, they can also set the people and environment on a collision course with a form of development that could be both exploitative and destructive.

In 2005, the warning signs were there already. Boven Digoel was the site of the first large-scale plantation in southern Papua, one that predated Yusak assuming office. It had been developed by a South Korean conglomerate and sparked lingering conflicts with the indigenous population, who complained that their land had been taken without adequate compensation and that their food sources and medicinal plants had been destroyed.

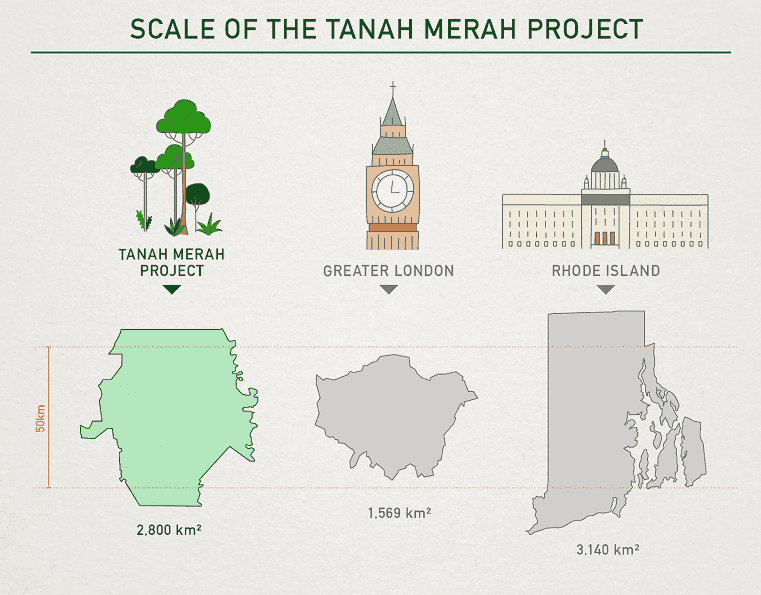

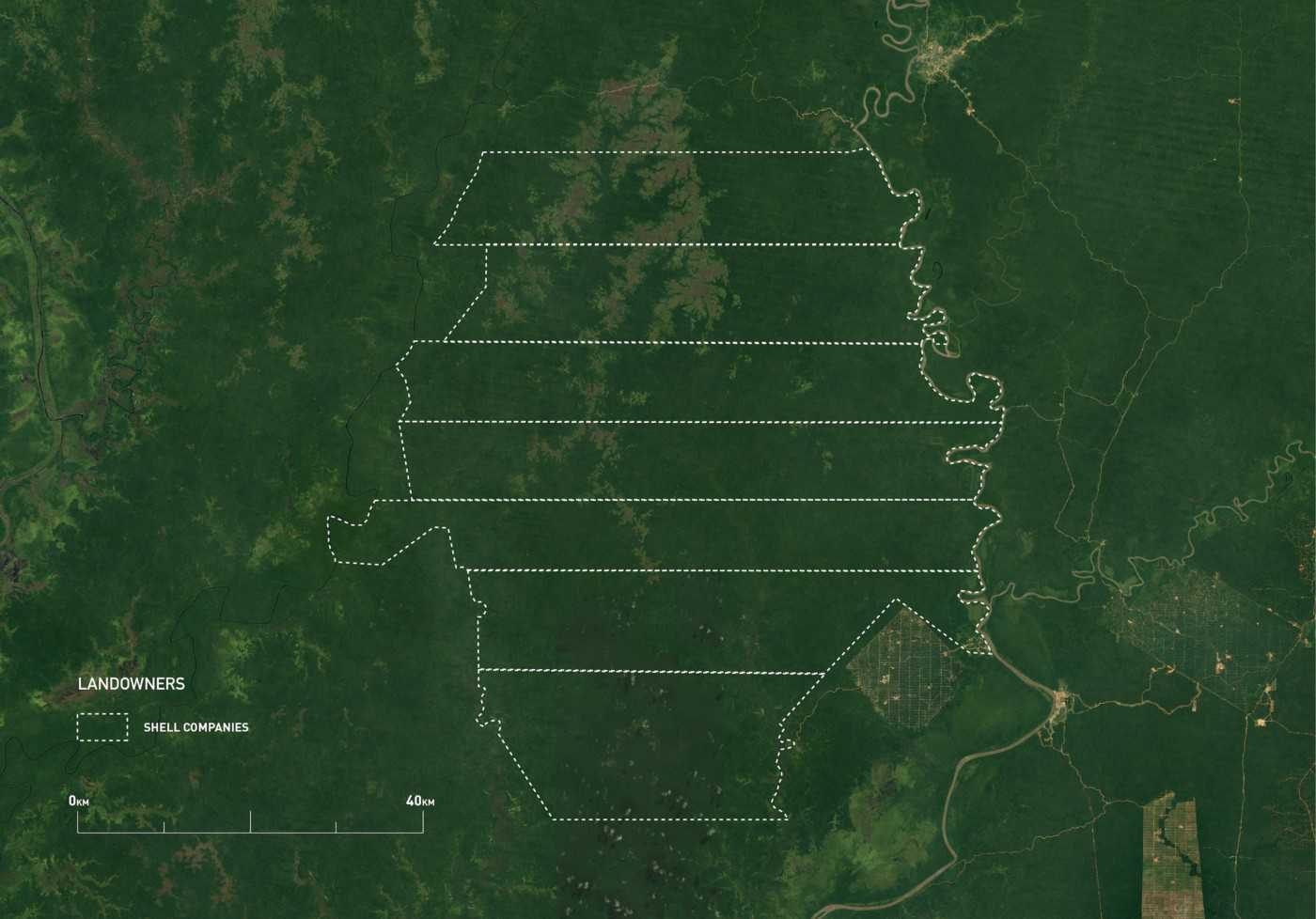

But Yusak did not heed these warnings. Government documents show that in December 2007 he exercised his power liberally, issuing permits that covered seven contiguous blocks of forest. The largest of them stretched more than 60 kilometres east to west. Seen on a map, they stacked together to form one single block measuring 2,800 square kilometres, some 10 percent of the district. Laid on top of London, it would cover the entire city nearly twice over. In Papua, it would create a giant hole in the rainforest.

The seven permits were issued to seven different companies. Yusak told us these were linked to a Malaysian conglomerate called the Genting Group. But two of its executives insisted that Genting had never incorporated or owned them. Determining who did proved easier said than done.

Corporate records obtained from a public government database in Indonesia reveal the seven companies were all set up within eight days of each other, in February 2007. Based on our investigation, they were registered to what appeared to be fake or front addresses. For some, the address did not exist. Others took us to small shops, where no one had any knowledge of the companies.

Each of the companies had two different shareholders. We tracked down one of these people, a woman in her late 50s, to her home, a room in a boarding house squeezed into a narrow alleyway in the south of Jakarta, Indonesia’s sprawling, smog-choked capital. She insisted she had never been involved in the company, or in such a role in any other company. At the time the company was incorporated, with her name as a founder, she was working as a janitor in a bank. The number on her national ID card proved that she was the same person listed in the corporate records. “I’m just a cleaner,” she said. “There’s no way I could make a company.”

The address of another shareholder, listed in the corporate records, took us to a slum in West Jakarta. The woman wasn’t home, but her father was selling fruit in the street outside. He said he had no idea his daughter had been connected to such a company. She too had been working as a cleaner in a bank at the time the companies were incorporated.

The evidence suggested that whoever formed the companies, it wasn’t the people named in the corporate records. The plantation could one day become the biggest in the country. But its very origins were cloaked in mystery.

The mysterious shell companies lay dormant, the idea of a mega plantation fading. Until, one day, Chairul Anhar turned up. Yusak told us he and Chairul first met in 2009, in a restaurant in Jayapura, the capital of Papua province. He said Chairul had arrived in the city on a private plane, flanked by a man named Dessy Mulvidas, who would play a central role in the scheme that followed. Chairul told him the Menara Group had bought the seven companies, but the initial permits had expired. He needed Yusak to renew them.

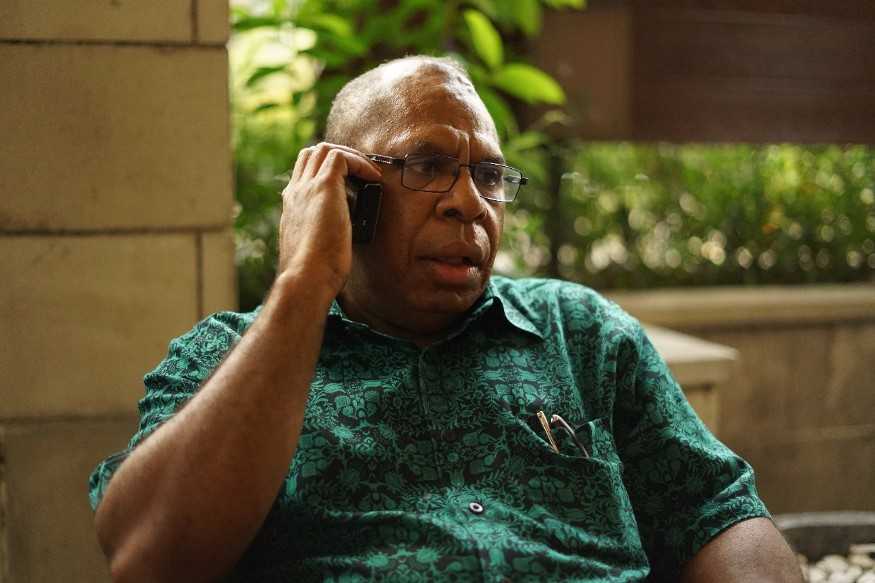

Yusak told us he received overtures from “many” investors seeking land in his district, almost all of which he rejected. “I wasn’t going to issue permits to just anyone,” he said, in a recent interview at a Jakarta mall. Chairul’s approach offered him the opportunity to revive a massive investment into the district, providing the bupati brought the permits back to life. But the businessman who had approached him was an unknown quantity. Who was Chairul Anhar?

Chairul’s occasional appearances in the media up to that point show he was not new to pitching grandiose schemes. In January 2007, he was described in news articles as the president of a company named PT Indomal Usahasama, which had plans for a $1 billion “Palm Oil Centre” on a remote island in the Molucca Sea. Four months later, he was identified in a trade publication as the president of PT Destini Marine, a company he claimed had booked orders worth $200 million to build tankers and cargo ships for clients across Europe.

The common threads running through both investments were bold claims, reports of unnamed Malaysian backers, and the fact that they disappeared without trace. Now, two years on, he presented himself as the owner of the Menara Group. The name, with menara meaning “tower,” conveyed the idea of an imposing conglomerate. In fact, there was little evidence to suggest the firm was more than paper thin. It had an office in a Jakarta tower block, but no track record of establishing plantations, no website, no online footprint.

In rural, cash-strapped Indonesian districts like Boven Digoel, local governments seek to rely on major investors to assume responsibilities extending far beyond the confines of their business. Under the umbrella of “corporate social responsibility,” they expect plantation or mining companies to construct roads and provide support for healthcare and education. In exchange for the riches to be made from palm oil, companies are legally required to plant and hand over plots of land — amounting to a fifth of their licensed area — to local farmers. Yusak told us he saw the Menara Group as a genuine investor that could deliver on these obligations, and that Chairul promised he would do so.

Within months of Chairul taking over the Tanah Merah project, it hit a major roadblock. One night in April 2010, Yusak was arrested by the KPK, Indonesia’s anti-graft agency. The agency had caught wind of a string of suspicious payments out of the Boven Digoel budget and swooped shortly after Yusak landed at Soekarno-Hatta International Airport in Jakarta. It marked a notable fall from grace. The year before, Yusak had led the campaign in Papua province for the eventual winner of Indonesia’s 2009 presidential election. Now, he was shuttled to a top-security prison in Jakarta to await trial.

When Yusak’s offences were later laid out in court, they were strikingly crude. Barely three months into his first term, he had arranged for the district government to take out a 6 billion rupiah ($580,000 in 2005) bank loan to buy a 3.5 billion rupiah ($340,000) oil tanker, and had the balance transferred to himself. Over the next two years, he repeatedly instructed a subordinate to withdraw money for him to use. By the time he was finished, according to the KPK, Yusak had siphoned off some 64 billion rupiah, then equivalent to almost $7 million.

Such brazen acts of corruption were not out of the ordinary in Indonesia’s regional politics. From 2003 onwards, as Indonesia embarked on a programme of decentralising power, bupatis, town mayors and provincial governors assumed control of large budgets and pliant bureaucracies. Largely left to their own devices, many found the temptation of corruption too much to resist. Skimming money from budgets and engaging in procurement scams proved to be common models, routinely prosecuted by the KPK. Investors also funded corrupt election campaigns — in which candidates handed out cash to secure votes — in the expectation of receiving business permits once their chosen candidate took office.

The KPK has also caught politicians receiving cash bribes in exchange for issuing permits for mines and plantations. Investigations and research, including by the KPK, show that this type of graft occurs far more widely than prosecutions might suggest. Yusak himself said payments for permits, at all levels of government, were the norm. “That’s the culture of Indonesia,” he told us, though he insisted he had not indulged himself. At the time of Yusak’s arrest in 2010, the NGO Indonesia Corruption Watch said more than 500 requests had been submitted to the KPK to investigate graft among regional leaders.

The Tanah Merah project remained at the early stages of what could be a lengthy permitting process. Chairul needed several permits for each of the seven companies — from the bupati, from the provincial government, and from the Minister of Forestry. Each of these permits was dependent on the one before. Yusak’s arrest threatened to create a bureaucratic freeze in Boven Digoel that could stall its progress. This was compounded by the fact that his term in office was scheduled to end just four months later, at which point a new politician, one potentially less conducive to such a giant scheme, might be elected to replace him.

Despite his incarceration, Yusak sought to continue his political career as if nothing had happened. Even though the KPK had never lost a case against a person it had charged with corruption, the district electoral commission allowed Yusak to stand for re-election. Though he was detained in Jakarta and unable to campaign in person, his campaign team continued on his behalf, supported on the trail by his wife, Ester Lambey. On Aug. 31, 2010, he won a second term.

In an interview with a reporter carried out in prison two months after his re-election, Yusak credited his victory to his achievements during his first term. “The community chose me because I can fulfil their needs, answer their wishes,” he said. A week after the interview was published, he was convicted of corruption, and sentenced to four and a half years in prison.

On the face of it, Yusak’s arrest should have frozen the permitting process, or at least his role within it. He was suspended from office three weeks before the election. For months, because he was in prison but had won the vote, the bureaucracy did not quite know what to do with him. The district parliament wanted him reinstalled as bupati; others, including the KPK, pushed back against that. The eventual compromise saw him inaugurated, in March 2011, but immediately made “non-active,” to avoid the farce of a district being administered from a prison cell. His running mate, Yesaya Merasi, was appointed acting bupati in his place.

But a trail of government documents we uncovered shows that while he was locked up on the island of Java, 3,600 kilometres from the Boven Digoel district capital, Yusak continued to play an active role in pushing through the Tanah Merah project. During this window of time, he signed decrees affirming that each of the seven companies acquired by Chairul had completed satisfactory environmental impact assessments. Yusak denied issuing these specific permits, but admitted to us he had signed documents in prison.

“At the time, I was officially still in office,” he said. “So, when there was a letter, I signed it.”

Part Two: 'The name of the game is to obscure the real person in control'

While Yusak was pushing through the permits from a prison cell, Chairul was searching for wealthy backers for the project in more luxurious environs. A well-connected Malaysian businessman told us he was approached by Chairul with an offer to take part in an ambitious deal in Papua. He recounted how Chairul had arrived at their meeting at a five-star hotel in Kuala Lumpur in a Bentley, and unfolded a map as he explained the project. The businessman, who passed on the opportunity, described Chairul as a “storyteller.” “People like Chairul, we call them Ali Babas,” he said, referring to a Malaysian idiom in which front companies gain access to contracts, and others deliver on them. “They don’t like to get their hands dirty.”

In a series of interviews this November, carried out by phone and WhatsApp video calls, Chairul, now 52, told us he had tried to secure financing to develop the Tanah Merah project. He estimated it would cost $1.4 billion to convert the forest into a plantation. But no one would back him, and so he turned to other, more established investors who could access the capital required.

The timing of the deals that followed, however, suggests he was hawking the rights to the project almost as soon as he had obtained them. “I don’t think their intention was to establish a palm oil business,” said a source who had first-hand knowledge of the Menara Group’s subsequent deals. “It was to establish the [companies], obtain relevant permits, and sell them to an investor. They’re selling paper permits, basically.”

By the end of 2012, most of the shares in six of the seven Boven Digoel companies had been sold on. Documents posted on the Malaysian stock exchange show that a 90 percent share in just two of the companies was sold for a total of $80 million. By the time that deal took place, the project had yet to break ground; the value was based solely on permits. The amount paid for the other four companies was never made public, but on the basis of those that were, the paper permits for all seven companies could together be worth more than $311 million.

Such permits have no official cost in Indonesia. District chiefs like Yusak are mandated to issue them, if they choose to do so, to whomever they deem fit to develop the land. The permits cannot legally be bought and sold. But one can, quite legally, buy and sell companies that hold permits. A thriving trade in shell companies with a single asset — a permit for a plot of plantation land — has persisted in the country over the past 15 years.

There are perfectly legitimate reasons for this to happen. The conglomerates that dominate the palm oil industry control their holdings through networks of individual subsidiaries, each of which operates a single plantation. If they decide to sell one of these plantations, they can do so by trading a subsidiary.

But the system provides considerable space for less legitimate practices. It provides bupatis, who have an established propensity for corruption, with the ability to generate assets worth huge sums with the stroke of a pen. Previous investigations by The Gecko Project and Mongabay revealed how two bupatis apparently cashed in on their control over licenses in Borneo by issuing them to shell companies owned by their cronies and family members. These cronies and family members then sold them on to major palm oil firms, who were willing to pay millions of dollars to people one step removed from a politician.

For those who want to disguise such connections, and move assets and money without scrutiny, there are options available. They can use offshore secrecy jurisdictions, like Cyprus or the Cayman Islands, which allow companies to be incorporated and make barely any information about themselves publicly accessible. They can also use nominee shareholders and directors, in which a front man effectively rents their name to the real owner, shielding the latter from public scrutiny.

The 2011 World Bank report “The Puppet Masters” reveals in detail how such corporate structures have been used to disguise the beneficiaries in some 150 cases of high-level corruption, collectively worth $50 billion, across the world. There are legitimate reasons for companies to use nominees, and in many jurisdictions it is legal to do so. In Indonesia, however, the practice was banned by the 2007 Investment Law.

We examined the ownership of the seven companies that held the rights to the Tanah Merah project after the Menara Group ostensibly took control of them. Corporate records show that on a single day in January 2010, the shares in all seven companies were transferred to 14 different individuals: two for each company, none of whom appeared more than once. Each was also named as a director or commissioner.

We visited the addresses listed for 11 of the named shareholders. One was a cheap boarding house, where no one had heard of the person named. At another address, the wife of a shareholder denied that he had been involved. The address of a third shareholder, Sarbani, turned out to be the home of his former mother-in-law. She said he had long since moved out. On paper, Sarbani had held 5 percent equity in a company valued at more than $40 million. But his former mother-in-law said he was a poor man with a low-paying job as a debt collector in Sumatra. She found the idea he could be a co-owner of a major plantation company faintly ridiculous.

A source inside the Menara Group, who spoke on condition of anonymity, confirmed that many of the shareholders were not the true owners of the companies, and that their names had been used as fronts. He identified one as Chairul’s driver. We also confirmed the driver’s wife had been named as a shareholder.

Some of the shareholders were more prominent figures. They included Chairul, though his name appeared on just one of the companies. Another shareholder was Mohamad Hekal, who was elected to Indonesia’s parliament in 2014. (Hekal did not respond to requests for comment.) There was also Dessy Mulvidas. He had appeared at Chairul’s side when he first met Yusak in 2009, and he had served as Chairul’s point man in Papua, the former bupati told us.

Dessy would appear throughout the scheme in the coming years — in Jakarta offices when the companies were sold, and in villages in Boven Digoel smoothing the way for the project to begin. The source inside the Menara Group described Dessy as the “pioneer” behind the scheme. “He’s the key,” the source said. “He took care of it from beginning to end.” The source with first-hand knowledge of the Menara Group’s deals described Dessy marshalling other shareholders.

The picture that emerged was of a web of individuals, some of whom may have held equity in the companies and others who clearly did not. Chairul did not seek to hide that he was pulling the strings. But the question of who he was pulling them for was impossible to answer.

“Certainly, the name of the game for many of these sorts of schemes is to obscure the real person in control,” Professor Jason Sharman, an author of “The Puppet Masters” and an expert in high-level corruption, told us in an email. “Companies with nominee shareholders and/or directors are a common way to do this.”

Chairul did not seek to hide that he was pulling the strings. But the question of who he was pulling them for was impossible to answer

The challenge highlighted in “The Puppet Masters,” and more recently by the sprawling Panama Papers investigation, is that opaque corporate structures can disguise who profits from companies’ activities. Where those profits are predicated on permits or contracts issued by government officials, it raises the spectre that those officials may have effectively held equity in the companies behind the scenes.

We found no evidence that any corruption was involved in the permit process or in any of the deals in the Tanah Merah project. Nonetheless, Chairul Anhar appeared to have generated more than $300 million-worth of assets based solely on government-issued permits. The ownership structure of the companies concealed the people who benefited when those assets were sold.

A growing body of international law recognises the role anonymous companies play in facilitating transnational corruption and money laundering. The US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA), for example, requires US companies to ensure they are not — knowingly or otherwise �— channelling money to foreign government officials. Tom Fox, a Texas-based attorney and FCPA compliance expert, told us the use of shell companies and nominee shareholders “would certainly raise multiple red flags” for any investor that fell under the jurisdiction of the FCPA.

“Such an entity would put a US company on very high notice that some illegal activity was going on,” he told us. He said the corporate structure behind the Tanah Merah project, while ostensibly controlled by the Menara Group, “stinks to high heaven.”

Part Three: ‘I don’t remember the names of all the shareholders’

In October 2011, a Malaysian construction and logging firm named Wijaya Baru Global, whose main shareholder was a member of that country’s parliament, became the first to enter into a deal with the Menara Group for a piece of the Tanah Merah project. Its business in Malaysia was troubled. It had been caught up in one of Malaysia’s largest ever corruption cases, stemming from the development of a new free-trade zone. In 2009, the chief operating officer of a Wijaya Baru subsidiary had been charged with defrauding a government agency in connection with the scandal. (He was acquitted in 2017.) Its timber business within Malaysia had dried up after its logging rights in Borneo expired. The Papua deal offered the firm a new, multibillion-dollar lease of life.

According to the deal announcement on the Malaysian stock exchange, Wijaya Baru, soon after renamed Tadmax Resources, agreed to buy 90 percent stakes in two of the seven Boven Digoel companies for $80 million. The four shareholders in these companies included Chairul’s younger brother, Indra Yunaidi, and Dessy Mulvidas, his right-hand man. The other two shareholders were nominees: Chairul’s driver and the debt collector. The source with first-hand knowledge of the deal said he thought the nominees were acting under Dessy’s instructions. (Dessy did not respond to requests to comment for this story and could not be found at either of his homes in Jakarta.)

The $80 million paid by Tadmax did not go through these shareholders. Instead, it was channelled through two additional shell companies in Singapore, each with a single shareholder. Our source inside the Menara Group confirmed that both were nominees, and that neither received any of the money. We reached one of them, Adwir Boy, on WhatsApp. He said he had had no involvement in the company, and that his name had been used by Dessy Mulvidas. Asked about the sale of the shares, he said, “I don’t know anything about that, Mr Vidas took care of it.” The money was paid to the nominees’ lawyers, stock exchange announcements show. From there the trail goes cold.

The October 2011 deal was conditional, with its completion predicated on the Indonesian Minister of Forestry, Zulkifli Hasan, issuing forest-release letters that would formally rezone the land for development. These letters, along with permits allowing the companies to harvest timber in the concessions, were the last key regulatory obstacles to the project going ahead. In early December, six weeks after the deal was announced, news emerged that Anuar bin Adam, a retired Malaysian army major and businessman, was vying to take control of Tadmax by buying out its main shareholder.

The report, in the New Straits Times, said Anuar’s takeover was backed by “a group of powerful Indonesian businessmen.” It cited a source close to Anuar as saying he could “open a lot of doors in Indonesia,” and that if he took control of the firm, this would become “self evident in the coming weeks.” The day after the report was published, Anuar’s takeover of the company was confirmed. Less than a week later, on Dec. 14, 2011, Zulkifli Hasan signed forest-release letters for both of the companies, enabling the deal to complete. (Anuar bin Adam did not respond to requests to comment.)

The following month, in January 2012, Tadmax made an influential new addition to its board. Da’i Bachtiar, a former chief of Indonesia’s national police, who had just completed a three-year stint as Indonesia’s ambassador to Malaysia, was appointed as an independent non-executive director. In an email, Da’i told us that Chairul had asked him to help Tadmax with the Menara Group’s investment in Indonesia, but that he was “rarely involved” in the business. He resigned from the board in 2014. He said he was unable to comment on the Menara Group structure and that he was not a shareholder.

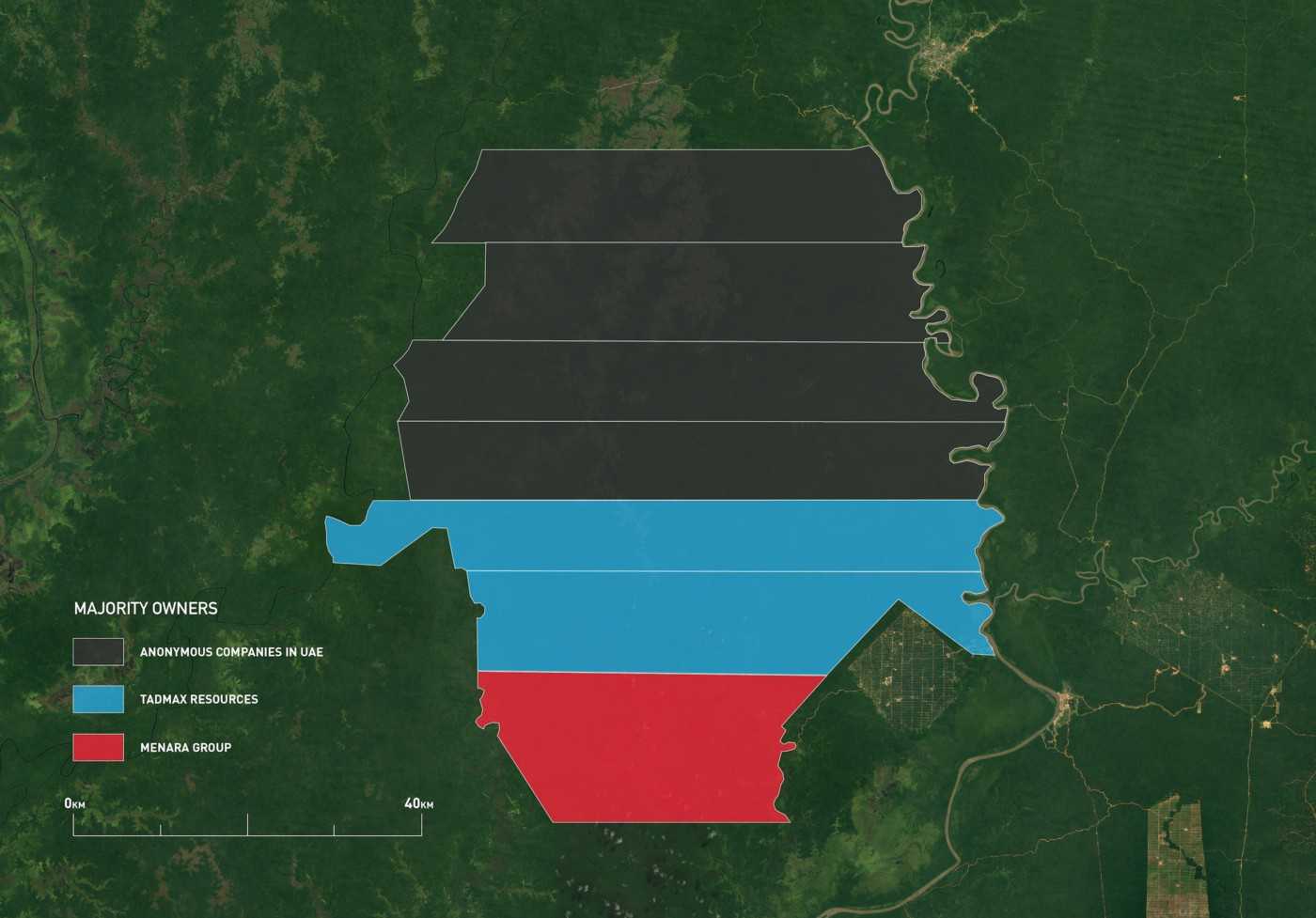

The Tadmax deals were public because the firm is listed on the Malaysian stock exchange, imposing a degree of transparency on its business. A larger chunk of the Tanah Merah project was sold in a far more secretive manner. Corporate records show that in the second half of 2012, 80 percent stakes in four of the other Boven Digoel companies were transferred to new shareholders in the Middle East.

The new shareholders were a quartet of companies with generic names and no online presence. They were registered in the United Arab Emirates (UAE); two in Dubai and two in the Ras Al Khaimah Free Trade Zone. These are secrecy jurisdictions, places where regulations are deliberately crafted to enable shareholders to hide their identities. The ownership of these four companies remains unclear to this day.

Greenpeace has published extensive evidence linking these four Boven Digoel companies to the Hayel Saeed Anam Group, a multibillion-dollar conglomerate owned by one of Yemen’s wealthiest families. The group is a major palm oil trader, via its Malaysia-based subsidiary Pacific Inter-Link. After the shares disappeared into the anonymous UAE firms, members of the Hayel Saeed Anam family joined the boards of the four Boven Digoel companies, corporate records show. However, Pacific Inter-Link has repeatedly denied that it or the Hayel Saeed Anam Group ever owned the companies. It told us in a statement that the family members had joined the boards “in their personal capacities.”

In all the deals, the Menara Group kept a small slice of the equity in the Boven Digoel companies. Tadmax and the anonymous UAE firms took between 80 and 90 percent. The remaining shares were transferred to new companies owned by Chairul, by some of the apparent nominees connected to him, and by a woman named Desi Noferita.

A court document (PDF) shows that Desi is the sister of Edi Yosfi, a low-profile but successful Indonesian businessman, who also held rights to other proposed plantations in Boven Digoel. Aside from his business interests, Edi is known as a powerbroker behind the scenes in the National Mandate Party, or PAN, an influential Indonesian political party. PAN is also the political party of Zulkifli Hasan, the Minister of Forestry, who had signed-off on forest-release letters for four companies in the seven months before Desi Noferita acquired her shares in them.

In response to questions sent via text message, Zulkifli, now the speaker of Indonesia’s highest legislative assembly, the MPR, said he was not involved in technical decisions while he served as Minister of Forestry, and that forest-release letters were issued to companies that complied with the requisite regulations.

Chairul denied that Edi Yosfi had any involvement in the project. “He’s a big businessman who doesn’t want to help with something like this,” he said. When asked about the role of Edi’s sister, with whom Chairul co-owns a company, he drew a blank. “I don’t remember the names of all the shareholders,” he said. Edi did not respond to requests for comment. His sister could not be reached.

Chairul did not comment on a detailed list of our findings presented to him in a letter. However, in a series of telephone interviews the week before publication, he made a string of elliptical and sometimes contradictory explanations for both the structure of the Menara Group and the deals with other investors. In response to the allegation that the shareholders prior to the sales were nominees, he described the Menara Group as a “consortium company” that represented the interests of other investors as well as its own. He declined to identify the other investors on the grounds that it would not be ethical to do so. “We’re a private company,” he said. “It would violate their human rights.”

Although company deeds and stock exchange announcements show that most of the equity in the Tanah Merah project was sold, Chairul insisted it was still owned by the Menara “consortium.” He described the deals as a “corporate exercise” that would allow him to access international financing, providing the $1.4 billion he estimated it would cost to develop the project.

Tadmax’s finances were in no great state either. But documents posted on the Malaysian stock exchange reveal how the firm planned to bankroll the project. An analysis commissioned by Tadmax estimated the value of timber in just two of the concessions at $1.7 billion. On that basis, logging the virgin forests across the entire project could yield almost $6 billion. Tadmax noted in its stock exchange announcements that the timber in the concessions would provide it with an “immediate and stable income stream.”

To take advantage of this veritable gold mine of timber, Tadmax declared its intention to construct a giant sawmill on the banks of the Digul River. The sawmill was to be a joint venture with Pacific Inter-Link and Shin Yang, a major multinational logging firm from Malaysian Borneo with a reputation for environmental damage, corruption and rights abuses. (Pacific Inter-Link has denied any involvement in the sawmill.) The spectre of the sawmill suggested the forests of southern Papua would not remain intact for much longer.

Part Four: ‘He got beaten half to death in that room’

One Sunday morning in April 2013, indigenous Auyu people in the village of Meto were praying in church when they heard speedboats coming upriver. When they walked down to see who had arrived in their village, they found a platoon of soldiers and police. The men were in a hurry, and told the Auyu to gather the remainder of the villagers at the small harbour, so they could get on with the purpose of their visit: to hand out envelopes stuffed with cash.

Meto is one of a string of villages whose land falls under the shadow of the Tanah Merah project. Since 2012, police and soldiers had made repeated appearances in the villages. Sometimes they disappeared into the surrounding forests to conduct mysterious surveys. News slowly emerged that the Auyu land was to be the site of a plantation project. But most Auyu had no idea how large the project was, or where exactly it would be. It rang alarm bells, but the villagers felt powerless. “We could see there were police and army in the speedboats,” one villager told us. “So we kept quiet. We were asking ourselves, ‘this must be connected to our land, but why are they using the police?’”

In Papua, the use of the security forces to escort representatives of logging and plantation firms is routine. “It helps them smooth their business,” said Franky Samperante, the director of Pusaka, an NGO that works with indigenous communities in Indonesia. Since Papua was subsumed into the Indonesian state in the 1960s, its people have had a fraught relationship with government forces. In a region in which oppression and extrajudicial killings have gone unpunished, the presence of police and soldiers has had a chilling effect. “It makes people feel unsafe,” Franky added. “They have a memory of violence.”

Villagers from Meto and neighbouring hamlets said their attempts to find out more about the Tanah Merah project, and to convey what they wanted from it, were stymied. According to those we interviewed, and information gathered by Franky and local priests, the villagers were made a string of promises to encourage their support for the project: that they would be paid a monthly stipend; that the company would provide electricity, educational facilities and healthcare. “They spoke to us with sweet words,” one man told us. “We were stupid to believe it.”

The meetings culminated on that weekend in April 2013 when the speed boats arrived in Meto. Police and representatives of the Menara Group, including Dessy Mulvidas, travelled through the villages handing out cash. Over the course of four days, they distributed the equivalent of $1.2 million in just four villages, according to the calculations of a local priest, Felix Amias. Though a fraction of the true value of the land, it was a huge sum for the villagers. But for many it was an ominous and unwelcome sign. They were not told what it was for, whether it was just “door-knocking” money, as Dessy said, or if they had now effectively sold their land.

A week later, the villagers were told to meet at a schoolhouse in Getentiri, a village in the southeast corner of the Tanah Merah project. They believed they would be afforded the chance to map their land, discover what overlaps there were with the project, and finally convey their views. But when they arrived the atmosphere was oppressive. The schoolhouse was ringed by soldiers. Inside were the police and a local military commander.

After they gathered inside the schoolhouse and waited for the meeting to begin, one of the villagers joked that they would need to eat and smoke cigarettes first, if they were to have such an important discussion. “There was one police officer in front,” a man from Meto told us. “He started beating him. That friend got beaten half to death in that room.”

The villagers were left with vague promises and a growing sense of coercion. They had been given a fortune in cash, but didn’t know what for. “We didn’t even know where the plantation was [going to be],” another said. “So, people in the village were living under this sort of pressure… This is our land, and the people from the company have bought it, they’ve given us money, and we don’t even know where it is.”

Part Five: ‘Someone in government must be breaking the law’

Boven Digoel was not the only district in eastern Indonesia in which Chairul Anhar had gained control of such a huge area of land. From 2010 onwards, while the Menara Group was laying the groundwork for the Tanah Merah project, the firm had been quietly moving ahead with a similar plan to develop a series of sugar plantations in Aru, a heavily forested cluster of islands some 500 kilometres west of Boven Digoel. These concessions covered 4,800 square kilometres, more than half of the entire archipelago.

The similarities between the two projects were striking. In Aru, the Menara Group had also used a maze of front companies to obtain the permits. Those permits had been issued by a bupati, Theddy Tengko, who, like Yusak, was eventually imprisoned for raiding the district budget, and who sought to hold on to office after his conviction. The permits in Aru had also been pushed through in the heat of an election campaign.

But Aru and Boven Digoel diverged in one critical way. In Aru, the eventual discovery of the project led to a groundswell of public opposition that grew into a powerful grassroots movement. The sheer scale of the project galvanised not only the indigenous peoples who inhabited Aru, but also a cohort of more seasoned activists based in Ambon, the provincial capital, who used their connections and know-how to build support for the movement in Indonesia and abroad. In April 2014, as the “#SaveAru” campaign reached a crescendo, Zulkifli Hasan, the then-Minister of Forestry, announced that the sugar plantations would not go ahead.

A critical component of the Aru campaign’s success was the ability of the activists to expose the brazen illegality of the licensing process. They discovered that late-stage permits had been issued without environmental impact assessments (EIAs) having been completed, as required by law. When the EIAs later appeared, it was clear they had been done without consulting most of the communities that would be deeply affected by the project, another legal requirement.

Semmy Khow, a professor who served on the commission convened by the government to review the assessments, told us that company officials had offered him bribes to sign off on them. “I didn’t want it,” he told us. Abraham Tulalessy, another professor on the commission, said the entire scheme had been “criminal.” “They should all go to prison,” he told us, referring to everyone who had played a role in pushing the permits through.

This raised an obvious question: Were the EIAs carried out for the Tanah Merah project just as flawed? Government documents showed they had been reviewed by a commission convened the day after the Boven Digoel election, in August 2010. A week later Yusak Yaluwo issued environmental permits from a prison cell, rubber-stamping the EIAs as valid.

Chairul insisted the permits were clean. “We’ve always followed the rules,” he said. “We’re not opportunists.”

But Franky Samperante, the activist who works with communities in Boven Digoel, questioned whether there had been any meaningful consultation, as the law required. He found that years after the assessments were approved, the villagers hadn’t even seen a map of the project. When they finally did, they discovered that their hunting grounds, sacred areas, forest farms — “most of the important places”, Franky said — were subsumed by it. “Often in Papua people are not given any information [about a development], then told to make a decision,” Franky told us. “It’s not based on factual information or truth. So the decision is effectively forced.”

When Franky set out to find the EIA documents so he could provide them to the villagers, the picture grew murkier. He checked with the forestry and development planning agencies in Boven Digoel; neither could supply them. At the provincial environment agency, he was told the EIAs hadn’t even been completed. This agency should have had copies of the assessments, but appeared not to be aware they even existed.

In Merauke, a coastal city south of Boven Digoel, we tracked down Ronny Tethool, who works for the local World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) office. He was ordinarily a member of the commission that assessed EIAs for Boven Digoel. He told us he had been invited to a preliminary meeting before the assessments for the Tanah Merah project took place, but was excluded from the commission that examined the results. “They weren’t shared [with us],” he said. “It was weird.” He pointed out that his office kept a record of all of the EIAs for the district, but had been unable to obtain those for the Tanah Merah project. “It’s like there’s a mafia hiding it,” he said.

The closest we got to finding the documents was a handful of photocopied pages from two of the EIAs, held in the office of an auditor in Jakarta. This suggested that the documents existed, but provided no clue to their contents. Franky arrived at the conclusion that they were being deliberately withheld. He suspected it was because if the true impacts were known, it would add grist to resistance from the communities. He observed that they had a legal right to see the documents. “If they’ve ignored those rights,” Franky said, “someone in government must have broken the law.”

Part Six: ‘The whole thing has to be shut down’

By 2015, Chairul Anhar had climbed to the top of Malaysian society. That year, his daughter married the son of Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, Malaysia’s Deputy Prime Minister. Chairul threw a lavish wedding reception at the Ritz-Carlton hotel in Jakarta. In February, he played golf with Da’i Bachtiar’s successor as the Indonesian ambassador to Malaysia at a Kuala Lumpur resort, as part of an event to encourage Malaysian investment in Indonesia. From then on, his presence at parties in Kuala Lumpur was documented on the website of the self-styled “high society” magazine Tatler.

But if Chairul’s public stature was growing, his stake in the Tanah Merah project — and those of his partners — was anything but sealed. Of the seven Boven Digoel companies, only two had acquired all the permits needed to begin operating. One of those companies, majority-owned by an anonymous firm in the UAE, with Chairul and Desi Noferita as minor partners, had begun clearing forest. But a trail of letters obtained from the current district administration shows that all seven of the Boven Digoel companies had become the subject of a sustained lobbying campaign aimed at revoking their permits so that new investors could take their place.

Beginning in December 2014, a Boven Digoel man named Fabianus Senfahagi, who held an influential position as head of the district’s indigenous peoples’ association, sent a string of letters to the district government urging it to cancel the permits originally issued to the Menara Group and reassign them to new investors. His letters argued that six of the existing companies had failed to begin operating, while the villagers in Boven Digoel were left “waiting and hoping” that the land would be developed.

In the two months leading up to the 2015 bupati election, Yusak’s successor, Yesaya Merasi, issued decrees revoking the permits held by the two Tadmax subsidiaries and by the seventh company, which was still owned by the Menara Group, and reissuing them to three new companies. Corporate records show the three new companies were owned by a man named Ventje Rumangkang and his family members. Ventje is best known as a founder of Indonesia’s Democrat Party, in 2001, but is predominantly a businessman with interests in mining and plantations.

Fabianus’s campaign continued over the next two years, as he sought to get the rights held by all seven of the original companies cancelled. In 2017, he succeeded in getting a fourth concession, owned by an anonymous firm in the UAE, reassigned to an Indonesian company named PT Indo Asiana Lestari.

The corporate records show that PT Indo Asiana Lestari is majority-owned by Mandala Resources, a shell company registered in Kota Kinabalu, in Malaysian Borneo. Mandala Resources, in turn, is owned by two men who also have a contracting firm that undertakes palm oil development. Neither they nor Mandala Resources have any discernible online presence.

In a brief phone interview, Fabianus insisted he was solely representing the interests of the villagers, who were “traumatised” by the Menara Group’s failure to develop the land. “So, we leaders looked for investors who would prioritise their rights,” he said. He pointed to the fact that the villagers had signed documents rejecting the Menara Group as evidence of support for his lobbying.

Benediktus Tambonop, who was elected to a five-year term as bupati in 2015, told us he had supported the new companies because he believed they had the backing of the people. Letters sent within government, advancing the permits for the new companies, repeatedly referenced letters sent by Fabianus.

Until he turned against the Menara Group, Fabianus had played an important role in helping it secure the rights to the Tanah Merah project. He had appeared with Dessy Mulvidas when he carried out surveys of the land, along with the police. He insisted to us that his incentive had solely been to secure the best deal for villagers. But his successor as head of the indigenous people’s association, Antonius Uweng Kandam, made a different case.

“What happened was not done in the interests of the community,” Antonius told us. “It was only in the interests of Fabianus.” He alleged that Fabianus had been paid to secure the consent of the villagers. “People don’t want this. It’s indigenous lands. Customary, communal lands.” Ronny Tethool, the Merauke director of WWF, similarly characterised Fabianus as a “broker” who had been paid by companies. Fabianus ended our interview when the subject of the new companies was brought up.

In an interview, Ventje Rumangkang stressed that the local communities were the true owners of the land, and that without their support the project wouldn’t go ahead. But in an open letter published in January 2017 by Pusaka, Franky Samperante’s NGO, villagers claimed Fabianus had “trapped [them] into signing documents we didn’t properly understand,” while trying to convince them to support the entrance of Ventje’s companies. In October 2017, Pusaka published further testimony from villagers who said they were being threatened with violence to coerce them into signing letters of support for the other new company, PT Indo Asiana Lestari.

Today these companies are still awaiting the final permits they need, from the provincial government and Ministry of Environment and Forestry, that will allow them to begin operating.

In public, to its shareholders, Tadmax continues to claim the rights to the land. Its most recent annual report made no reference to any revocations or the increasing fragility of its permits. Chairul too presented it as unfinished business. He said he had already spent hundreds of billions of rupiah in the time since he first acquired the permits. “Nothing is a problem as long as you’ve got politics and money,” he said. “Have a little patience. It will all turn out alright.”

“Nothing is a problem as long as you’ve got politics and money”

According to Felix Amias, the Boven Digoel pastor who has worked on behalf of local communities, many villagers have been left increasingly perplexed by the succession of companies claiming rights to their land. Recently, Felix began to receive a steady stream of requests to help resolve the confusion. He in turn reached out to Yusak, now out of prison, who he believed could serve as a guide among the interests now circling. Together, the duo set off to delve into the mess of overlapping claims.

We met them at a mall in Jakarta this October. They had recently sat down with Ventje Rumangkang, and were planning to visit government agencies. Yusak was tapping up the Boven Digoel and Papua bureaucracies to find out more. But they remained in the dark over who, if anyone, was in the ascendancy. “The story takes so many twists and turns that we’re all confused,” Felix said. “The people too. If the story isn’t clear, how are we going to solve the problem?”

Yusak, who had lit the fuse on the forest more than a decade ago, had come to the view that the entire project had been one big mistake. It would do irreparable harm to the people of the district, he now said. “I don’t want to sin against my people,” he said. “The whole thing has to be shut down.”

Part Seven: ‘It feels like the clouds have fallen’

When a team from Greenpeace flew by helicopter over the rainforest of Boven Digoel earlier this year, a thin mist gathered over the unbroken green canopy that stretched to the horizon. At one point, they passed a flock of some two dozen hornbills flying close to the apex of the trees. Then they arrived at the border of the Tanah Merah project. The verdant landscape gave way to a muddy red soil, pockmarked with oil palms planted in regimented patterns, and grey, fallen trees.

The land clearing started by the Digul River, close to the village of Anggai, and was working its way westwards. Villagers told us their sources of clean drinking water had turned red, the colour of the soil, and that they had to walk increasing distances to find food. Those journeys were harder now that the forest canopy no longer protected them from the sun. “All the natural resources that God has given us… It feels like the clouds have fallen,” said an elder man from Anggai. “All destroyed in an instant.”

Today, an area larger than Manhattan has been cleared within the project. Two companies are now operating, both owned by anonymous firms in the UAE, 7,000 kilometres from Boven Digoel. Chairul is still a minor shareholder and is set to make a fortune if just this one section of the project is completed. He now serves as secretary general of the Indonesia-Malaysia Business Council, and routinely appears in photos in media reports next to people from the highest levels of politics in both countries. He boasted in his interview that he is friends with government ministers, and has “friendly chats” with the new Prime Minister of Malaysia, Mahathir Mohamad.

The area of forest cleared to date represents just 2 percent of the total project. But the giant sawmill is now under construction. Tadmax has now sold its share in the joint venture behind the mill. Now it is co-owned by the notorious logging firm Shin Yang and Malindo Investments, an anonymous company registered to an accountant’s office in a Dubai tower block. Chairul insisted that the delay in getting the mill built had been a key “bottleneck” preventing the project from moving faster. Without it, the companies had nothing to do with the timber. If the mill is completed, the destruction of the surrounding forests is likely to dramatically accelerate.

The secrecy surrounding the project has left even the district government in the dark. On the sidelines of a grub-eating festival in Boven Digoel this September, the current bupati, Benediktus Tambonop, told us he himself remained clueless as to who held many of the permits. After taking office in 2015, he discovered the district was encumbered by more licenses than any other in Papua. It had fallen to the KPK, the anti-graft agency, he said, to tell him there were more than 20 companies with permits in his own district. The owners only began to emerge when he announced on the radio that he would begin revoking those permits.

“One by one they started to call us,” he said. He discovered the companies were headquartered in Singapore and Malaysia, with no presence in Boven Digoel. “To this day, we’re still trying to find out even where their offices are located and how they got their permits.”

The twin subjects of corporate secrecy and licensing for plantations now preoccupy activists, journalists and government officials beyond the borders of Boven Digoel. Over the past year, a succession of analyses has revealed how the largest palm oil and timber conglomerates in Indonesia — those historically responsible for the catastrophically high levels of deforestation — have disguised the extent of their operations through “shadow companies,” entities managed by the conglomerates themselves but kept at arm’s length through front shareholders. Many of these companies channel profits through opaque corporate structures facilitated by offshore secrecy jurisdictions.

“To this day, we’re still trying to find out even where their offices are located and how they got their permits”

Over the past few decades, but mostly in the last two, some 210,000 square kilometres of Indonesian land has been ceded to plantation firms. Permits were issued in opaque circumstances, principally by district politicians who have demonstrated considerable susceptibility to corruption. This year, the KPK completed its hundredth case against a regional leader, a haul that is widely believed to be the tip of the iceberg. Many of the same politicians who were convicted of budget skimming and procurement scams have played an important role in the licensing spree that has placed an area of land the size of Kansas in the hands of private firms.

Both of these subjects merit further investigation: to discover who is hiding what, and how they got their assets. But the Tanah Merah project emphasises the intriguing overlap between these two phenomena. It raises the prospect that finding out who is behind a web of shell companies and front shareholders may also reveal exactly why those shell companies were granted valuable assets in the first place.

The government agenda may be moving slowly toward answering these questions. In September this year, Indonesian President Joko Widodo ordered a government review of all oil palm plantation permits in the country, as part of his temporary freeze on new permits. In March this year, another presidential regulation came into effect that requires companies to disclose the identity of their “beneficial owners” to the government. If implemented, it could pull away the façade of any nominee shareholders.

The fate of this huge swathe of forest — and the indigenous peoples who rely on it — is still hanging in the balance

The combination of these two developments could shed further light on key aspects of the story behind the Tanah Merah project. It is a story that is far from over, with the fate of this huge swathe of forest — and the indigenous peoples who rely on it — still hanging in the balance. The decisions that have taken it to this point were mired in secrecy; a tussle continues behind closed doors that may decide who ends up with the rights to the land.

Four years ago, the Menara Group’s plan for a string of giant sugar plantations in Aru was dragged into the light and dissolved under the scrutiny. For now, the Tanah Merah project remains in the shadows.

“The whole thing is full of secrets,” Pastor Felix told us. “Only people with problems have something to hide.”

To see films and photos from Papua, and further stories in the Indonesia for Sale series, follow The Gecko Project on Facebook and Instagram.

11th January 2021: This article originally stated that the minor shareholder of PT Indo Asiana Lestari is Rimbunan Hijau, one of the world’s largest tropical logging firms. The minor shareholder is named PT Rimbunan Hijau Plantations Indonesia. However, there is no evidence that the Malaysian logging conglomerate of the same name is connected to it.