- Indonesia’s new president brands himself as a successful businessman worth over $130 million, who controls almost half a million hectares of Indonesian land.

- But many of the companies in which he owns shares appear to be inactive, according to evidence reviewed by The Gecko Project. Activists argue the companies’ permits should be revoked.

- One company that is currently active, a timber firm that appears to be owned by Prabowo’s political allies, has recently been logging rainforest in Borneo.

- Nonprofits have called for more transparency on the business interests of members of Indonesia’s incoming government.

This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network.

When Prabowo Subianto is inaugurated as president of Indonesia on October 20, it will mark a remarkable turnaround in his personal fortunes. At the turn of the millennium, Prabowo was living in self-imposed exile; a disgraced former special forces officer dismissed from the military over his alleged role in ordering the kidnapping of human rights activists.

Over the next two decades he edged his way back to the heart of politics in the world’s third-largest democracy. He ran unsuccessfully for vice president or president four times, entered government as defence minister in 2019, became an honorary four-star general in February and finally won the top prize in March—rebranding from uniformed hardman to cuddly grandfather in the process.

As he moved from pariah to political heavyweight, Prabowo was undergoing a parallel reinvention as an entrepreneur.

The president-elect’s self-made wealth has become part of his personal brand. “When I retired [from the military], sometimes I couldn’t even afford to pay for the toll road,” he said during the election campaign. “So I became a businessman.”

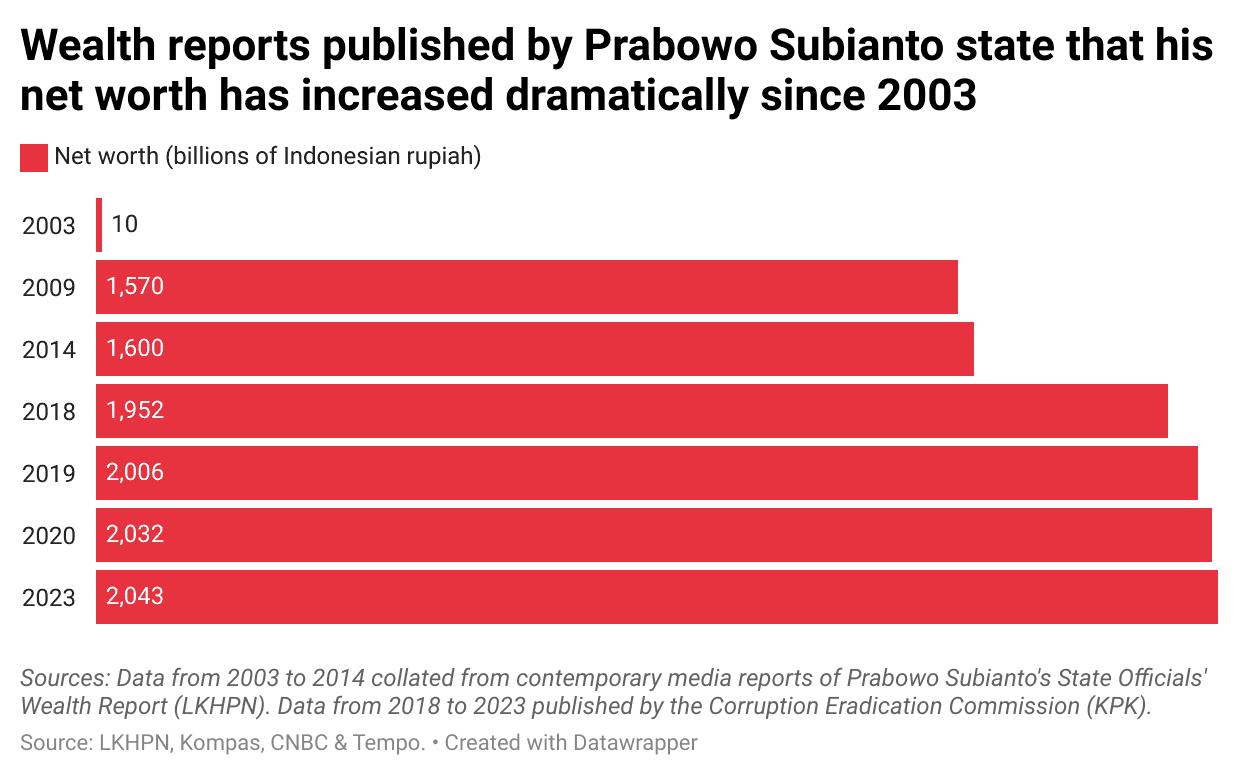

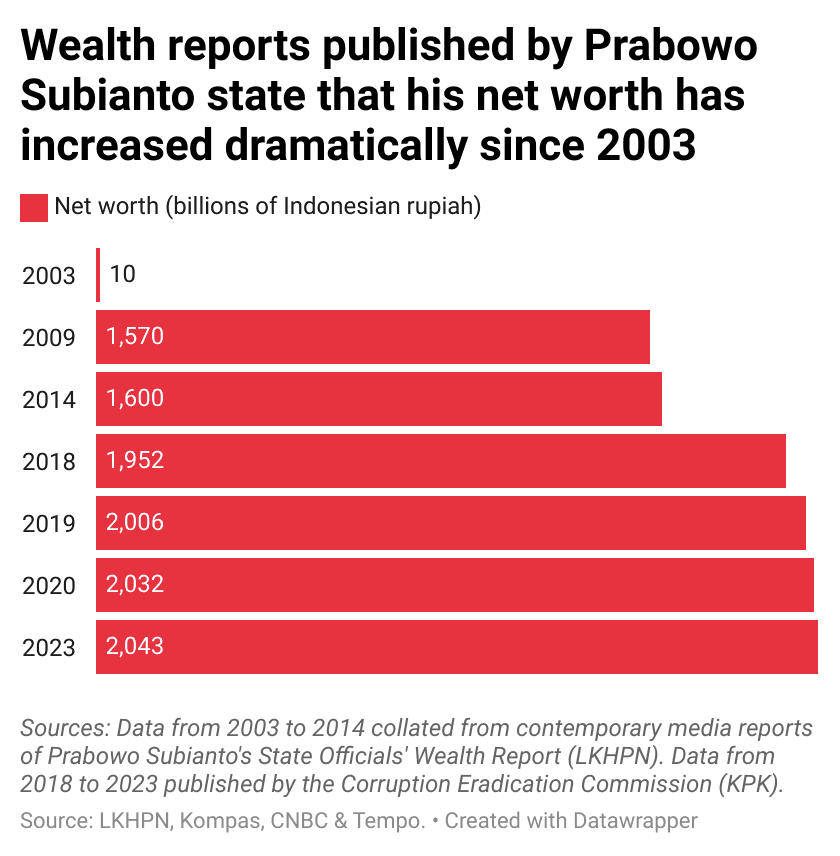

In the years since he left the military his net worth has soared to more than 2 trillion rupiah—approximately $133 million—according to his official declarations. In media profiles, he is reported as owning multiple companies involved in coal mining, forestry and other sectors. At a campaign event in January, he took a rival to task for underestimating the scale of the land over which he presides. “It’s not 340,000 hectares, it’s closer to 500,000 hectares,” he said.

Such a figure would place the area under Prabowo’s control at almost seven times the size of Singapore, a landbank to rival almost any of the agribusiness conglomerates that play a central role in the Indonesian economy.

The Gecko Project set out to build a profile of Prabowo’s businesses using public reports, corporate profiles, government permit records, satellite imagery, interviews with former employees, and visits to his forestry and coal concessions. The evidence we found suggests that many of the companies presented in media reports as part of Prabowo’s thriving business empire are likely to be inactive, while some businesses that he is publicly associated with are actually owned by other people.

One of the few companies that was a going concern collapsed in 2013, leaving workers chasing payments they said they were owed. His brother Hashim Djojohadikusumo, who appears to be playing a prominent role in the incoming administration, has claimed to be bankrupt, in part because he has spent a fortune bailing out Prabowo’s failing business and bankrolling his election campaigns.

Producing a full accounting of Prabowo’s businesses is challenging, however. In some cases the paper trail runs cold, with documents missing from official registries. In others, his connection to companies is opaque, with layers of shareholdings leading not to the president-elect, but to a web of his political allies.

Nonprofits argue that it's important for politicians to be transparent about their business interests. “My fear is that nepotism and collusion could become permitted again, as long as it is in the interests of big goals such as [tackling] poverty,” said Danang Widoyoko, secretary general of Transparency International Indonesia.

Prabowo did not respond to a detailed list of questions or a request to comment on our findings.

Through the mill

High-level officials in Indonesia and candidates for public office are required to submit “wealth reports” to the anti-corruption commission, known as the KPK. According to Prabowo’s most recent wealth report, his net worth of 2 trillion rupiah is comprised principally of “securities”, which commonly refers to shares in companies. The official record shows these securities valued at 1.7 trillion rupiah, a figure that has not changed in successive annual reports since 2018. Recent wealth reports have not provided any detail beyond the total value. But according to media coverage of his 2014 submission, his securities comprised shares in 26 companies. Submissions are not independently verified by the KPK.

Using media and NGO reports, and a website set up in Prabowo’s name in advance of the 2009 presidential election, The Gecko Project identified 20 companies Prabowo has reportedly owned, across sectors including industrial fishing, palm oil production, forestry, pulp and paper, and coal mining.

One of Prabowo’s first forays into business after he was expelled from the military was his acquisition of a company he renamed Kertas Nusantara, whose prize asset is a giant pulp mill on the banks of a river on the east coast of Borneo. It had been owned by Mohamad ‘Bob’ Hasan, a disgraced crony of former president Suharto, who was convicted of corruption in 2001 for embezzling tens of millions of dollars of government funds.

Prabowo bought the mill in the early 2000s using a $201 million loan from a state-owned bank, Bank Mandiri. Jusuf Kalla, a prominent politician who later served two terms as vice president, recently stated to the media that he had personally helped convince Bank Mandiri's CEO to allow Prabowo to buy the company. The loan later became part of a criminal probe by the attorney general, though Prabowo was never charged and the investigation was dropped.

It was not long before Prabowo was struggling to service the loan. In 2005, he was bailed out by his younger brother Hashim, who had made a fortune in an oil deal in Kazakhstan. This established a pattern, with Hashim bankrolling the business and political ambitions of Prabowo for years to come. "He always gives Prabowo what he wants," one family friend told Forbes in 2010.

By 2009, the mill was described on Prabowo’s website as a sprawling facility with schools, housing and a factory that produced “world-class pulp with a production capacity of 1,500 tons per day for 350 days per year”. The true picture was not quite as positive. Two years later, Kertas Nusantara was being threatened with bankruptcy proceedings by a creditor and hundreds of workers had reportedly been fired. By 2019 the firm was still dealing with allegations that it had failed to pay its employees’ wages.

When The Gecko Project visited the site in August this year, the school buildings were abandoned, enveloped by overgrown shrubs. The mill itself was desolate. Walls in its now-unused buildings displayed posters featuring photos of Prabowo, declaring support for his presidential campaign. “Don’t worry Pak Prabowo, we’re with you,” said one, purportedly from a workers’ union.

The nearby village of Pesayan was once bustling and economically thriving, kept alive by the workers who flooded through it to work in the mill, buying food and gasoline from stalls along the side of the road. Today it is quiet.

Some of the Pesayan villagers were retained as security guards, but most stopped working in 2014. A villager named Jafar, a father of seven, was paid 6 million rupiah (around $400) per month working as a supervisor in charge of the mill’s water treatment facility. According to Darma, his 50-year-old wife, he was promised a retirement payment of nearly 100 million rupiah (around $6,500) when it finally shut down. “But my husband hasn’t received the money,” she said.

Like others in the village who lost their jobs or shut down their shops, as the trade from the mill employees dried up, they have turned to fishing and farming to feed themselves. “At least we can get fish and rice for free,” said Darma.

Mining manoeuvres

Another major component of the purported Prabowo empire is his coal mining assets, some of which were acquired in controversial circumstances.

In 2008, a UK-listed company named Churchill Mining discovered a massive payload of coal in concessions in East Kalimantan that had previously been held by Prabowo’s companies, but that Churchill believed had been allowed to lapse. After the discovery of the coal, Prabowo’s firm successfully reclaimed the land with the support of the local district head, Isran Noor—prompting Churchill to accuse Prabowo and Isran of “asset stripping.” The case was eventually determined at the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes, a global arbitration institution, which dismissed Churchill’s claims.

The year after news of that scandal broke, Isran Noor issued mining permits to half a dozen companies owned by Prabowo, handing him, on paper, concessions amounting to around 85,000 hectares. Prabowo obtained two more concessions in a neighbouring district. In 2018, Prabowo and his party backed Isran Noor in his campaign to become governor of East Kalimantan province. Isran did not respond to our questions.

“Indonesia’s economy has always been characterised by people acquiring assets by being close to power, or by being in power themselves,” said Ward Berenschot, a professor at the University of Amsterdam who is researching conflicts of interest among Indonesian political elites. “Being in politics is not just about politics, but also a way to acquire assets. It skews the political system towards prioritising business interests over any other interests, like labour or the environment.”

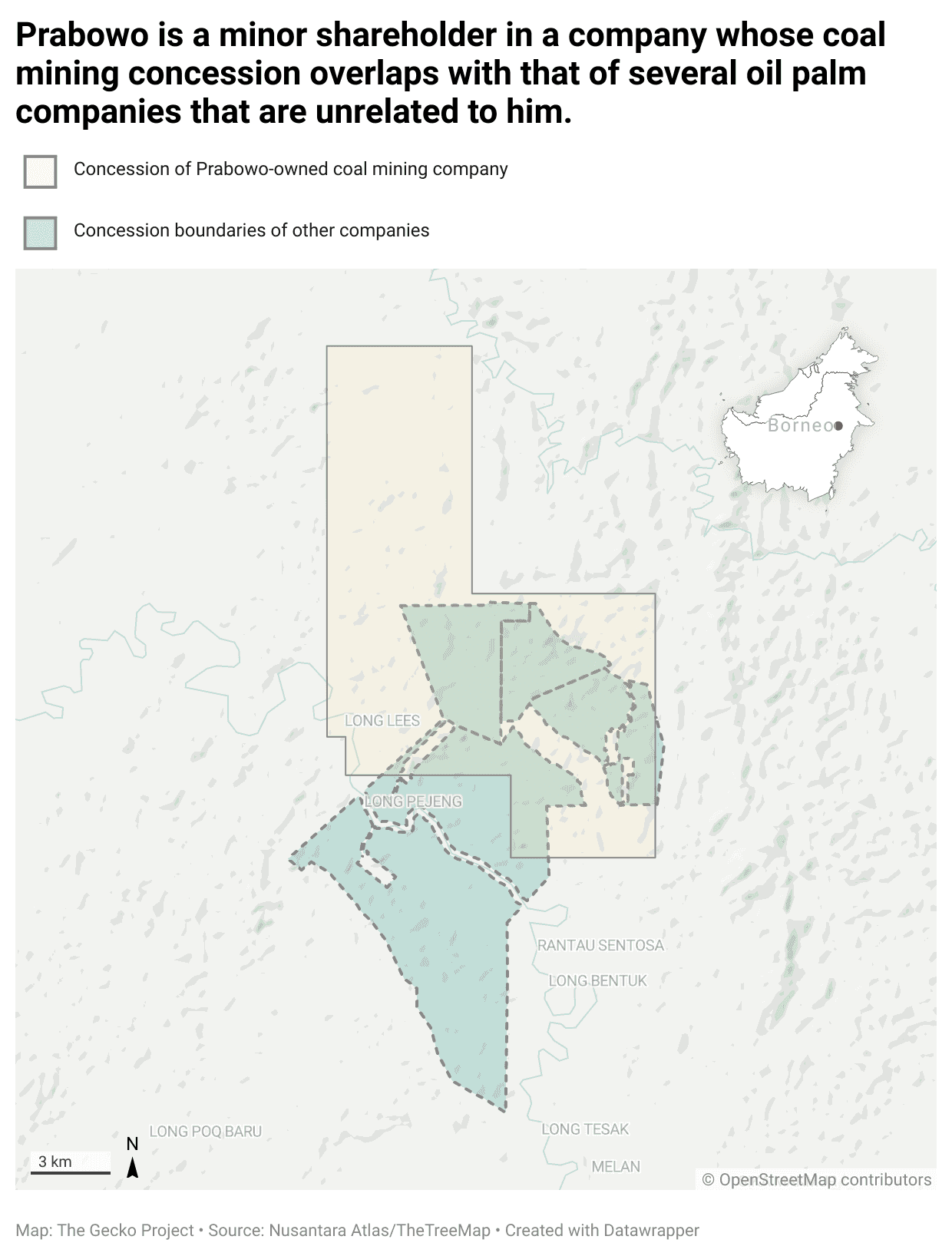

Prabowo’s coal concessions appear to have been abandoned, however. Satellite imagery analysis commissioned by The Gecko Project shows that, as of the end of 2023, some of them had been cleared—but not for coal mining. Instead they have been used to cultivate either fast-growing timber species or oil palms.

A review of permit records and other sources suggests the timber and palm oil plantations are not being developed by Prabowo’s companies, but by unrelated companies that happen to have overlapping permits for the land. This is not a rare phenomenon in Indonesia, where chaotic spatial planning and competing control over permits have created overlapping concessions. But it appears in these cases that it is the other claimants, not Prabowo, that have made use of their permits.

The Mining Advocacy Network, known as JATAM, has carried out extensive research in East Kalimantan, the province in which Prabowo’s mining concessions are located. Farhat, a JATAM campaigner, said that the sector had become increasingly disordered after locally-elected officials, like Isran Noor, assumed control over issuing permits in the early 2000s. Sometimes permits were issued to finance elections, or to reward the members of campaign teams.

Farhat said that it was common for companies to acquire coal concessions but not actively exploit them. Instead, he said, they used their rights to the concession as collateral to help them obtain bank loans, sometimes to be spent on unrelated business ventures.

The ownership puzzle

Corporate records obtained by The Gecko Project reveal another notable aspect of Prabowo’s purported business empire — the fact that he has become a minor shareholder in many of the companies associated with him, or has no shares at all.

In some cases this is because he or his family divested. In 2010, the majority stake in five coal mining firms he had founded was transferred to Ithaca Resources, controlled by the Indonesian billionaire Agoes Projosasmito, who has extensive interests in mining and energy. Agoes did not respond to a request for comment.

A company called Tidar Kerinci Agung was one of only four we identified that is evidently a going concern, in this case operating an oil palm plantation in West Sumatra. Prabowo’s then-wife—daughter of former Indonesian president Suharto—and his brother Hashim were the founding shareholders of the company in 1984. Prabowo appears as a board member, but never a shareholder. Corporate records show it was sold to a Singapore-registered company in 2018.

Prabowo’s relationship with some other companies is hard to ascertain, as the relevant records have disappeared from the government corporate registry, rendering it impossible to identify the current shareholders. That is the case with three firms, including a commercial fishing company described on Prabowo’s campaign website in 2009 as having a $10 million fleet and producing 1,000 tons of tuna per month. That company has left little discernible trace online, aside from being frequently named in media reports as belonging to Prabowo.

Companies reportedly owned by Prabowo

Combined, the area of land controlled by the plantation and mining companies associated with Prabowo hold permits amounting to 395,818 hectares, according to our review of available permit records. This is short of the 500,000 hectares Prabowo had claimed, but in excess of the 340,000 hectares raised by others during the campaign, suggesting it accounts for most of his claimed land assets. But we could only find evidence that three of the 13 companies that hold these permits are operating, and Prabowo does not own shares in any of them.

| Company name | Sector | Is the company active? | Does Prabowo hold shares in the company? |

|---|---|---|---|

| PT Nusantara Energy | Coal | No | Yes |

| PT Nusantara Kaltim Coal | Coal | No | Yes |

| PT Kaltim Nusantara Coal | Coal | No | Yes |

| PT Nusantara Wahau Coal | Coal | No | Yes |

| PT Nusantara Berau Coal | Coal | Yes | No |

| PT Nusantara Santan Coal | Coal | No | Yes |

| PT Nusantara Prima Coal | Coal | No | Yes |

| PT Batubara Nusantara Kaltim | Coal | No | Yes |

| PT Erabara Persada Nusantara | Coal | No | Not known |

| PT Kertas Nusantara (formerly PT Kiani Kertas) | Forestry | No | Yes |

| PT Kiani Hutan Lestari | Forestry | No | Not known |

| PT Belantara Pusaka | Forestry | No | Not known |

| PT Kiani Lestari | Forestry | No | Not known |

| PT Tanjung Redeb Hutani | Forestry | Yes | Not known |

| PT Tusam Hutani Lestari | Forestry | No | Yes |

| PT Tambang Sungai Suir | Mining | Not known | Yes |

| PT Gardatama Nusantara | Security | Yes | Yes |

| PT Jaladri Swadesi Nusantara | Fisheries | Not known | Not known |

| PT Tidar Kerinci Agung | Palm Oil | Yes | No |

| PT Chakra Namira | Not known | Not known | Yes |

Of all the companies in which Prabowo still has a direct stake, The Gecko Project could only find evidence that one was operating. Gardatama Nusantara, incorporated in 2001, states publicly that it provides security services to multinational companies, including Chevron and BP. The company operates in the plantation, forestry and mining sectors, according to its website. When The Gecko Project visited East Kalimantan this year, Gardatama was providing security to one of Prabowo’s former coal firms.

Arvind Ganesan, director of economic justice and rights at Human Rights Watch, noted that Gardatama Nusantara was working for “companies in industries that have had serious human rights impacts over the years”. He said that Prabowo should disclose his business interests and set up a blind trust to manage them while he was in office, to avoid conflicts of interest. “It’s better for Prabowo to declare his ownerships and to put a distance from those companies to ensure impartial government oversight of them,” he added.

A presidential regulation issued in 2018 requires companies to disclose their “beneficial” owners. But of the 20 companies that Prabowo has reportedly owned, only four name him as a beneficial owner.

Timer Manurung, the director of the environmental nonprofit Auriga Nusantara, noted that the registry was not necessarily accurate. “The problem is that it’s self-declared,” he said. There is no system for verification.” He added that it was important for all public officials to be transparent about their business interests.

There is a particular public interest in disentangling Prabowo’s relationship with one company, which is already having an impact on the rainforests of Borneo. Tanjung Redeb Hutani holds the rights to clear-cut a vast area of forest in East Kalimantan. The concession is so large that on its own it could account for more than a third of Prabowo’s purported 500,000 hectare landbank.

The available public records do not name Prabowo as a shareholder, but six of his close political allies have served as shareholders and board members of either Tanjung Redeb Hutani or a series of companies that own it. They include senior members of his political party, Gerindra; people who have played leading roles in his election campaigns; and at least two people to whom he has reportedly acted as a mentor. The majority shareholder until at least 2019 was Edhy Prabowo who, while not a family relation, is widely reported to have had a close personal and professional relationship with Prabowo.

Edhy Prabowo enjoyed a soaring political career as a Gerindra member, rising to become minister of maritime affairs and fisheries. His political career was abruptly cut short in 2020 when he was arrested, and later convicted, for corruption. Hashim’s reaction to his conviction pointed to Edhy’s closeness to Prabowo, as much as his disappointment in Edhy’s downfall—he described him as a “child” Prabowo had “adopted from the gutter”.

The Edhy Prabowo corruption case

While Prabowo was not implicated in the corruption scandal that took down Edhy Prabowo, its tentacles touched companies connected to him. Edhy was convicted of taking bribes to expedite permits for exporting lobster larvae, shortly after he had lifted a ban on such exports in his capacity as fisheries minister.One of the companies subsequently issued with an export permit was Agro Industri Nasional (Agrinas), which was overseen by Prabowo and a coterie of Gerindra politicians. They included, for example, Sugiono, a Gerindra legislator and Agrinas commissioner, who has also served as a director of one of the companies that owns Tanjung Redeb Hutani.

Another man caught up in the scandal was Syammy Dusman. In 2021 the anti-corruption agency seized 3 billion rupiah, around $195,000, from Syammy, money it suspected was connected to the bribery of Edhy Prabowo. Syammy was not subsequently charged and today serves as the director of Prabowo’s security company, Gardatama Nusantara. Syammy and Gardatama did not respond to a request for comment.

According to the Indonesian government’s register of beneficial ownership, Tanjung Redeb Hutani is now owned by Aris Marsudiyanto, another member of Prabowo’s campaign team, who also serves as director. Satellite imagery analysis and government records show that it has recently been logging rainforest in East Kalimantan.

Timer Manurung, of Auriga, said that Prabowo should publicly declare any interests in Tanjung Redeb Hutani, as well as any other companies with which he is associated. He called for individuals involved in implementing public policy who have associations with Prabowo to declare their business interests, too. “It’s important for the public [to see] that decisions are made in the public interest,” he said, adding that any future misuses of power could have “enormous” negative consequences for the environment.

PT Tanjung Redeb Hutani did not respond to our request for comment.

Money troubles

Despite the net worth presented by his wealth reports, Prabowo has himself admitted that he has struggled to convince banks to back his business ventures.

In a high-profile interview with a popular journalist, Najwa Shihab, in the early days of the presidential election campaign, Prabowo admitted that “many of my factory assets have stalled, because I can’t get credit” and attributed this to his not being in power for 20 years. Several months later at a meeting of entrepreneurs, he quipped that bankers would be “afraid” of him becoming president, because they had turned him down for loans. “It’s really difficult for us to ask for credit,” he said.

Bhima Yudhistira Adhinegara, director of the Jakarta-based Center of Economic and Law Studies, speculated that Prabowo’s status as a high-profile politician, the alleged human rights violations—which led to him being banned from entering the US, until he was named a minister—and his track record as a businessman could all contribute to his difficulties in securing bank loans.

“If you look directly at some of Prabowo's businesses, for example [Kertas Nusantara], many of them are also losing money,” he said. “This means that Pak Prabowo is not actually a reliable businessman.”

Hashim, too, is facing financial problems. Swiss authorities have been chasing Prabowo’s brother over unpaid taxes since the mid-2000s. Lawyers acting on his behalf have sought to convince the authorities he is insolvent—in part, he says, because he has spent $420 million bailing out Prabowo’s business and financing his election campaigns.

In his attempts to prove that he could not pay his debts, in 2018 Hashim presented a report by a Jakarta law firm showing that he had assets of around $18 million, but debts of around $166 million. The image that emerges of Hashim from his own submissions to the court is of a divorced, debt-ridden businessman, who has squandered a fortune on his brother’s failed endeavours.

“It’s quite clear they’ve been hard up for money quite critically after every election campaign,” said a long-time observer of Indonesian politics, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of negative consequences. “If they were doing business with any acumen they wouldn’t be in that situation over and over again.”

Whether Hashim is as hard-up as he claims is an open question. The Swiss courts have repeatedly ruled against him, pouring cold water on his claims that he cannot pay his debts, and questioning whether he is really divorced. This year they began auctioning off properties in his wife’s name in Switzerland and seized bank accounts in the name of his children.

Hashim’s legal wrangles have not discouraged him from playing a prominent role in the incoming administration, even before Prabowo takes office. In September, he told reporters he was picking cabinet ministers. “I have identified two, three, or even four Taruna Nusantara alumni who are likely to become ministers in the upcoming cabinet,” he said, referring to the high school from which many of Prabowo’s close political allies have graduated. Among the names being considered were two Gerindra members who have served as directors of Tanjung Redeb Hutani, the timber company.

Hashim did not respond to a request to comment on our findings.

Escaping the axe

Companies owned by Prabowo and his political allies have been able to hold onto their claims to land across Indonesia despite efforts by the state to take back unused permits. In recent years the government has tried to undo decades of chaotic land management by cancelling inactive and overlapping concessions.

In 2022, president Joko Widodo announced his administration was revoking more than 2,000 mining permits and 192 in the forestry sector. One of the forestry companies linked to Prabowo was included in the cull, but the others appear to have been spared. The mining ministry’s website shows that his coal companies still hold permits that will stretch into the next decade.

Activists from Greenpeace, JATAM and Auriga Nusantara all argue that the inactive forestry and mining concessions should have been revoked, according to the government’s own policies. But they noted the inconsistent application of these policies, particularly towards politically-connected or powerful individuals. “The ones who are being disciplined, in our experience at JATAM, are only those who don't have connections or who happen to be on a different political bandwagon in the presidential election,” said Farhat. “Those who have power and position aren't affected.”

The failure to revoke these concessions means that Prabowo assumes power and control over Indonesia’s climate policies with extensive interests in coal and forestry. It also leaves open the possibility that these concessions will, ultimately, be exploited.

There is evidence that at least one business is expecting a change in fortunes. After a decade of inactivity the timber mill on the banks of the Berau river may yet come back to life. When The Gecko Project visited the site this year, employees said that an audit of the facility was underway, with a view to firing it up again next year, in the months after Prabowo takes office.

This article was updated on 16th October to clarify the activity in Tanjung Redeb Hutani’s concession.

Read more reporting from The Gecko Project here.

Join The Gecko Project's mailing list to get updates whenever we publish a new investigation.