When Rita Widyasari, the former head of Kutai Kartanegara district in Indonesian Borneo, was sentenced to 10 years in prison last year for taking bribes in connection with a string of plantation and mining projects, it exemplified the success of the nation’s anti-corruption agency in closing such cases.

Since its formation in 2004, investigations by the anti-graft agency, known as the KPK, have led to the conviction of a string of politicians for similar offences. But research by the KPK, political scientists, activists and journalists suggests the problem extends far beyond the cases that have gone to court.

The proliferation of permits for mines and plantations over the same period has left a tapestry of projects — some legitimate, some less so — across Indonesia. These are ripe for investigation by journalists, activists and citizens.

For those who lack the expansive powers of the KPK, finding evidence of corruption in the issuance of licenses can be challenging. But in investigations by The Gecko Project and Mongabay over the past three years, we have identified a number of red flags — clues that some impropriety has potentially taken place. Permits, and the ways in which they are traded between brokers and investors, leave a paper trail that can be interrogated to find these clues.

This article defines these red flags, explains what they reveal, and details the methods that can be used to identify them. While they do not individually provide irrefutable evidence of corruption, they can be used to identify leads or to inform other areas of research. Whether it is land-rights conflicts, criminalisation, companies operating illegally, or something else, identifying questionable practices in the licensing and trade of mining and plantation companies can provide essential context.

What data will you need?

There are two key types of information that will be used in these methods. The first is shareholder, or ownership, data. The second is permit data. All of these red flags can be identified by cross-checking information within and between these data sets.

Ownership data can be obtained from the Indonesian government’s corporate registry, hosted by the Ministry of Law and Human Rights. Indonesian citizens can acquire profiles for individual companies that will show either the current shareholders and board of directors (for a fee of 50,000 rupiah, or $3.60) or the entire history of shareholders and directors since the company was formed (for 500,000 rupiah, or $36). For these purposes, the full records are the most useful.

In theory, permit data can be obtained from state agencies. But in recent years the government has sought to prevent citizens, journalists and NGOs from obtaining it, in violation of the law governing freedom of information. So realistically the data needs to be obtained from other sources. Many NGOs, particularly at the provincial level, have data sets for plantation and mining permits. They are often incomplete and potentially inaccurate, but can be sufficient to apply these methods.

Most of the major holding companies operating plantations and mines in Indonesia are listed on stock exchanges, often in Indonesia, Malaysia or Singapore. When they acquire new assets, they have a duty to announce details of the deal via stock exchange websites. These announcements will often include the identity of the vendors, the permits they are effectively buying, and the value of the deal. As such, they present a rich and complete set of data.

The ‘red flags’

The permits are expedited

The bureaucratic process required before a plantation firm can start operating should take several months. First, a company must obtain a location permit, or izin lokasi, usually from the district chief, or bupati. This defines an area of land in which the company can negotiate with existing landowners, and carry out an environmental impact assessment, or EIA (known in Indonesia as an AMDAL).

The EIA process involves consulting with local communities who will be affected by the project. The findings must be approved by a panel of academics, NGOs and community representatives. Once approved, the company can apply to for a plantation business permit (Izin Usaha Perkebunan, or IUP). This usually takes place at the district level, but sometimes the IUP must be issued by the province.

In some cases, bupatis expedite the permit process. When they do so, the most common casualty is the EIA. One motivation for doing so is that it is takes time and money to carry out the process as required by law. Another is that if done properly, it gives communities and NGOs and communities an opportunity to interject in the process, raising concerns over the location, extent or impact of the project.

Expediting permits in this way is a criminal act. It raises questions over the motives of any politician who would do it.

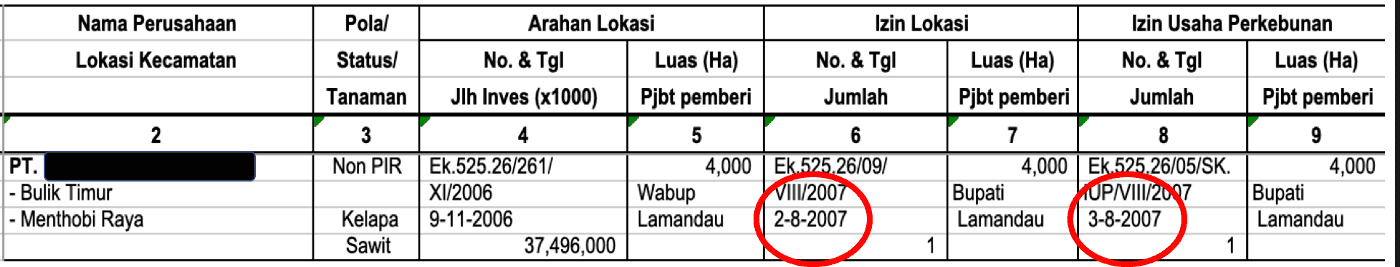

If this has occurred, it can be identified by comparing the dates on which location permits and IUPs were issued. If the two permits are issued within weeks of one another, it is usually an indication that the EIA process has not been carried out. In many cases, permit databases will show that they have been issued on the same day.

The above record from a Central Kalimantan provincial government database shows a company that was issued a location permit and IUP just a day apart, presenting strong evidence that the bupati allowed the company to skip a vital step in the permit process.

Shell companies used as vehicles for trading permits

Plantation companies are free to approach local governments directly to apply for permits. But in many cases the permits are first obtained by middlemen or brokers, with the sole intention of selling them on.

Technically speaking, a permit for a plantation cannot be transferred from one company to another. But there is a workaround. To do these deals, a broker can form a shell company — a legal entity that exists only on paper, with no assets or history of trading — to which a permit can be issued. The broker then sells the company, and the permit attached to it, to an investor who actually intends to develop the land.

The allure for brokers is obvious. They can conjure up assets worth millions of dollars simply by trading paper and exploiting connections with the politicians who issue permits and the companies that want them.

In some cases, a broker may be a front for, or acting on behalf of, a politician. As a KPK prosecutor told us, it would be “suicide” for a politician to put their own name on a company — it would be obvious they were acting to enrich themselves. But by putting the names of relatives or associates on corporate records and using them as proxies to carry out the deal, they can monetise their control over land in a way that avoids detection.

This red flag can be identified by examining the date a company was formed and when changes in ownership took place, either through company profiles obtained from the law ministry or stock exchange announcements posted online. That date can then be cross-referenced with the date the company acquired permits, either through permit databases or, again, stock exchange announcements.

If a company was formed, licensed and sold in a small window of time, it is a strong clue that the people behind it had no intention of actually developing a plantation, and it could well be a vehicle for selling permits. While this is not necessarily illegal, it raises questions over the politician’s motive for issuing permits to such a company, and it raises the prospect that they benefited from it.

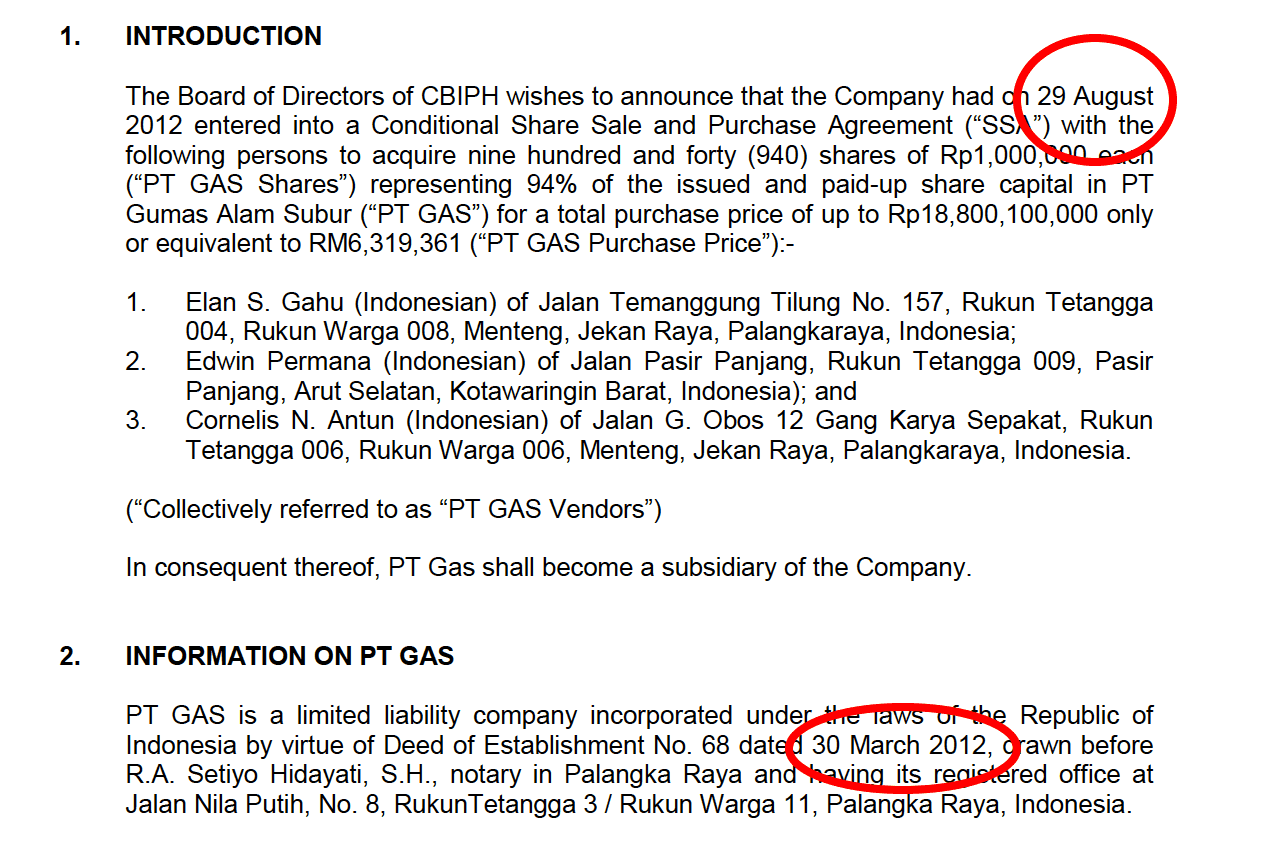

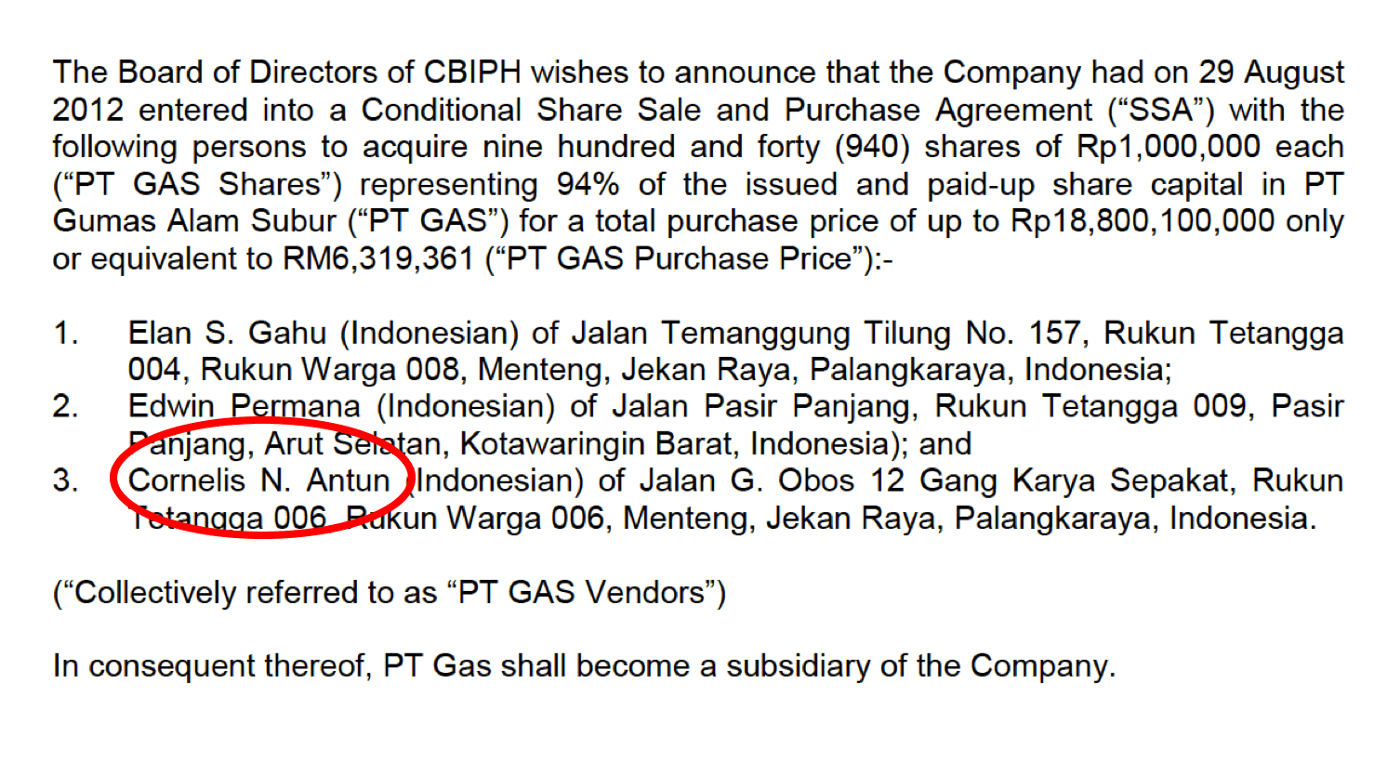

The following stock exchange announcement from 2012 shows how three brokers formed a company in March 2012, obtained a permit four months later, and agreed a deal to sell almost all of their shares in the company a month after that.

We have published two investigations (here and here) in which these permit-trading schemes appear to have been deployed by cronies and relatives of politicians, and were likely used to directly or indirectly benefit the politicians.

Deals involving politicians’ family members and associates

Where land deals involve the close associates or even family members of a politician, such individuals may be acting on behalf of the politician to disguise the fact that the politician is benefiting from it. It may be an act of nepotism — itself a criminal offence in Indonesia.

The vendors in land deals can often be identified through stock exchange announcements. Online research or interviews with people familiar with the political landscape in the relevant jurisdiction can identify connections between the vendor and local politicians.

In the case highlighted above, the stock exchange announcement named one of the three men who formed and sold the company as Cornelis N. Antun.

Court records and news reports reveal that Cornelis Nalau Antun was in fact the protégé of Hambit Bintih, the bupati of Gunung Mas district in central Borneo. Cornelis also served as the treasurer of Hambit’s election campaign. Stock exchange announcements showed how permits issued by Hambit transformed Cornelis’s shell companies into a $9.2 million asset.

It is not unknown for the children of district heads to be named as shareholders in shell companies used in permit-trading schemes. This practice featured in our 2017 investigation into the plantation boom in central Borneo’s Seruyan district.

This analysis explores the role of natural resource deals in funding election campaigns in Indonesia more broadly.

Issuing permits close to elections

Studies by the KPK, research by political scientists, and our own investigations have provided irrefutable evidence of the connections between election financing and plantation permits. Elections for district head and provincial governor are expensive, with the costs far exceeding the campaign finances available through legitimate sources.

It is possible to identify cases where there is a risk licenses have been used to finance election campaigns by looking at when permits were issued and when companies were traded.

This is an imperfect approach: there are legitimate reasons for these things to occur close to election time. But the closer they occur to an election, the more attention they merit.

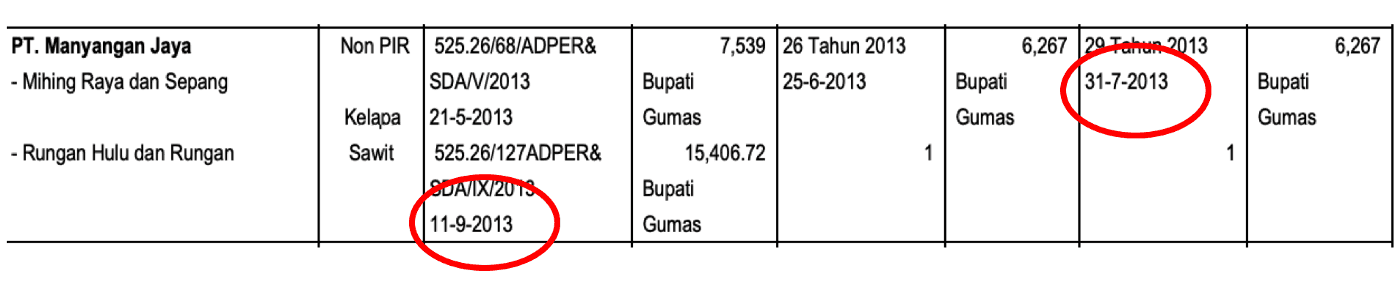

In the case referenced above, Hambit, the Gunung Mas bupati, issued an IUP to a company owned by his protégé, Cornelis, on July 31, 2013, a little over a month before he stood for re-election. He issued another principle permit (left in the graphic) on Sept. 11, seven days after the vote.

Another investigation we published recently showed how Theddy Tengko, the bupati of Aru Islands district, issued a spate of permits to a single company to develop a giant sugar plantation less than a week before the vote for his re-election. The licensing process betrayed multiple instances of illegality, and Theddy was later convicted of corruption for unrelated offences.

The Mining Advocacy Network, or JATAM, an Indonesian environmental NGO, has analysed permit data across the country. In several districts, it found a spike in new permits for mines in election years and the following year.

Multiple permits issued in a single jurisdiction in a small window of time

Individual plantations are capped in Indonesia at 200 square kilometres, more than three times the size of Manhattan. Companies can obtain several plantations through different subsidiaries, up to a limit of 1,000 square kilometres. (The allowable size of individual concessions and the total is doubled for companies operating in Papua and West Papua provinces).

Where multiple individual companies obtain permits on the same day, or in a small window of time, it is an indication they may be controlled by the same investor. In some cases, they might do this to exceed the statutory limits on the area assigned to one company. In the Aru Islands, for example, Theddy Tengko issued permits to one group amounting to more than double the legal limit.

Even where they remain below the limit, such cases merit attention because the risks of corruption are greater. By issuing multiple permits, a politician can generate an asset worth many millions of dollars for a company, several times larger than if a single license was issued.

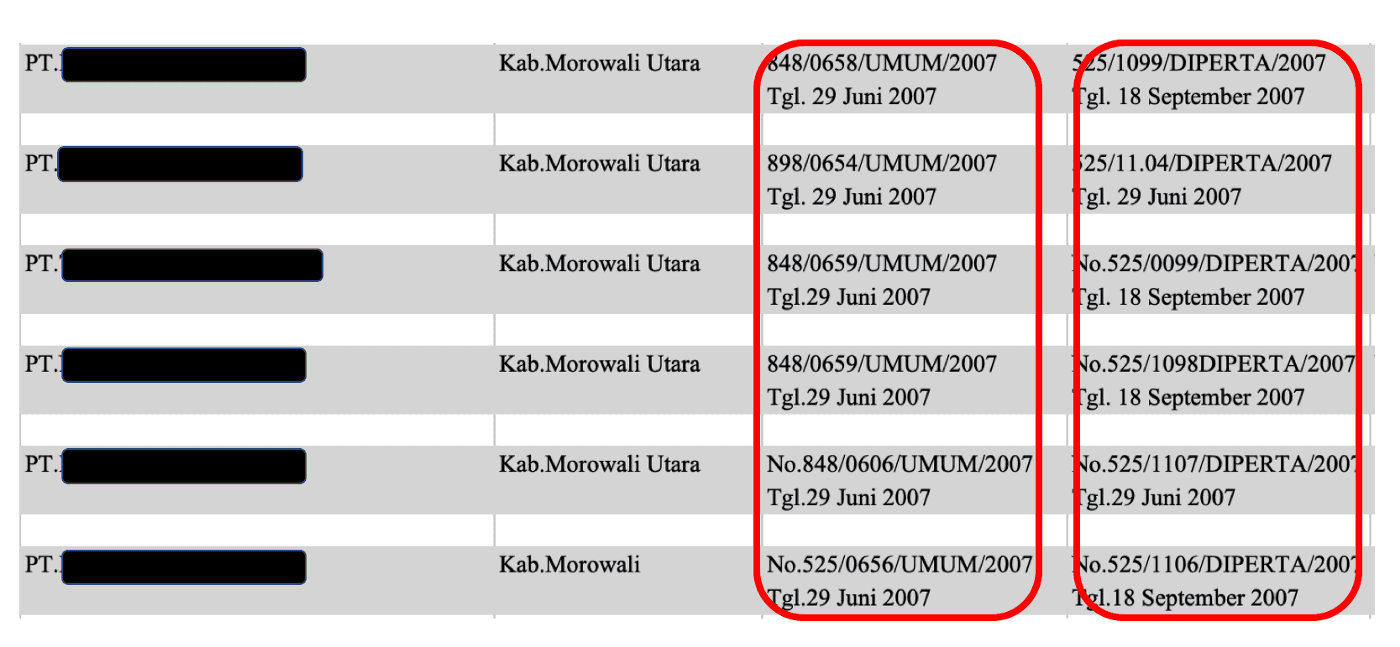

This section of a plantation permit database from Central Sulawesi province provides a good illustration of this risk. The database shows that six companies obtained permits on the same day in June 2007, raising the prospect that the same investor is behind them, and that the bupati has created a huge — and potentially illegal — asset.

The potential illegality is suggested by other red flags. Two of the companies received IUPs (in the right column) on the same day as their location permits (left column), a strong indication the permits were expedited and the EIA process ignored. In the case of the other four, the IUPs were issued just three months later, which is likely still insufficient time to carry out an EIA.

The election for head of the district in which these permits were issued took place on Nov. 5, 2007 — the same year the permits were issued. This provides no evidence of wrongdoing, but merits further attention due to the risk the licenses were connected to election financing. Identifying the shareholders of the companies through the government corporate registry (company profiles) and carrying out research into their connections would be a possible next step.

Permits issued by a politician convicted of corruption

The KPK has convicted dozens of district heads of corruption, for offenses ranging from accepting bribes, to procurement scams, to raids on state budgets. Many of these politicians have issued multiple licenses for plantations and mines. But where the corruption case is not connected to licenses, they do not come under investigation.

To date, we have carried out three investigations into politicians who were convicted of unrelated corruption schemes, who also oversaw plantation projects riddled with improprieties. Yusak Yaluwo, the former bupati of Boven Digoel in Papua province, siphoned off money through the procurement of a shipping tanker, then signed documents for a mega plantation while he was in prison. Theddy Tengko stole the equivalent of $4.7 million from the district budget and then illegally issued IUPs in the absence of EIAs. Hambit Bintih bribed a judge, after he had issued licenses to his re-election campaign treasurer. In two of the cases, the plantation licenses remained in place.

It does not automatically follow that a corrupt politician will solicit bribes for issuing permits, or trade them through nominees. But such cases are ripe for investigation. Corruption cases also leave an extensive body of evidence that can be used to support investigations into land deals.

Summary

Where they occur individually, none of the red flags we’ve identified provide strong evidence of corruption or any other form of illegality. Where a number of them occur in the same case, however, they paint a much more compelling picture. This nonetheless should still be viewed as a starting point to generate ideas for where further investigations could be directed.

They could also be used to provide context and a better understanding of why other problems are occurring that are being investigated by activists or reporters. Why, for example, a company is consistently able to evade law enforcement for clearing beyond its boundaries. Or why a powerful local official has failed to support communities in their efforts to seek justice, after their land has been forcibly taken.

Ultimately, examining permits and land deals in this way is a means to trace flows of money and assets, a process that is essential to holding power to account.

To see other articles, films and photos from The Gecko Project as they come out, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube. Sign up to our mailing list here. The Gecko Project stories are available in Bahasa Indonesia at our Indonesian site here.