The videos show soldiers driving excavators while armed with machine guns

And patrolling villages in full battle gear

They are among thousands of troops the Indonesian government has deployed to the region of Papua

To transform a vast area of rainforest into farmland

Politics of Deforestation

Fear and Raiders in Papua

How thousands of Indonesian soldiers are forcing through a vast agricultural project in indigenous lands and forests

This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network.

Romanus Moiwend had just returned from a successful hunting trip in the forests of southern Papua last September when he saw an excavator roll onto his community’s land and start clearing forest.

His land, near the village of Wanam on the western half of the island of New Guinea, was filled with tropical forests and swamps where his clan had fished and hunted for generations.

Romanus, an athletic 30-year old, stood in front of the excavator and blocked its path. He asked the driver to stop. “Let us talk to our families first,” Romanus said.

As the stand-off continued, around a dozen soldiers emerged from the forest nearby and headed towards Romanus. They were fully armed.

Romanus pleaded with them to stop. But the soldiers insisted the land had to be cleared of trees. “The land belongs to the government,” they told him, in Romanus’ recollection. “You can’t get in the way.”

The indigenous people of Papua, like Romanus, are organised into clans, who manage their land collectively. The light touch of their livelihoods has left Papua with some of the largest tracts of intact rainforests in Asia, and biodiversity to rival many places on earth. The land provides clans like the Moiwend with food, medicine, fish, and curious animals to hunt, like flightless cassowary birds.

But now, that land is in the crosshairs of a massive “food estate” programme, driven by Indonesia’s president, that aims to create more than 1.6 million hectares of rice fields and sugar plantations. The scheme is so large, activists believe that it could lead to more deforestation than any other single project in the world.

Faced with the soldiers, Romanus felt powerless to stop the destruction of his clan’s forest. The soldiers then escorted him for half a kilometre to his bevak — a wooden hut where indigenous Papuans rest during hunting trips.

As they walked, Romanus felt nothing but fear.

Romanus then told his uncle, Marianus Moiwend, a 47-year-old fisherman, about the encounter. “We couldn’t do anything,” Marianus told The Gecko Project. “Because all these [soldiers] were armed. There were no people here: we were in the middle of the forest,” he said.

“We have no power.”

Across southern Papua, in the months leading up this incident, many indigenous Papuans had troubling interactions with the military. Soldiers arrived in villages and told them they had to accept the government’s “food estate” programme. They planted stakes in customary land. Soon after, excavators arrived and began bulldozing community forests and farms.

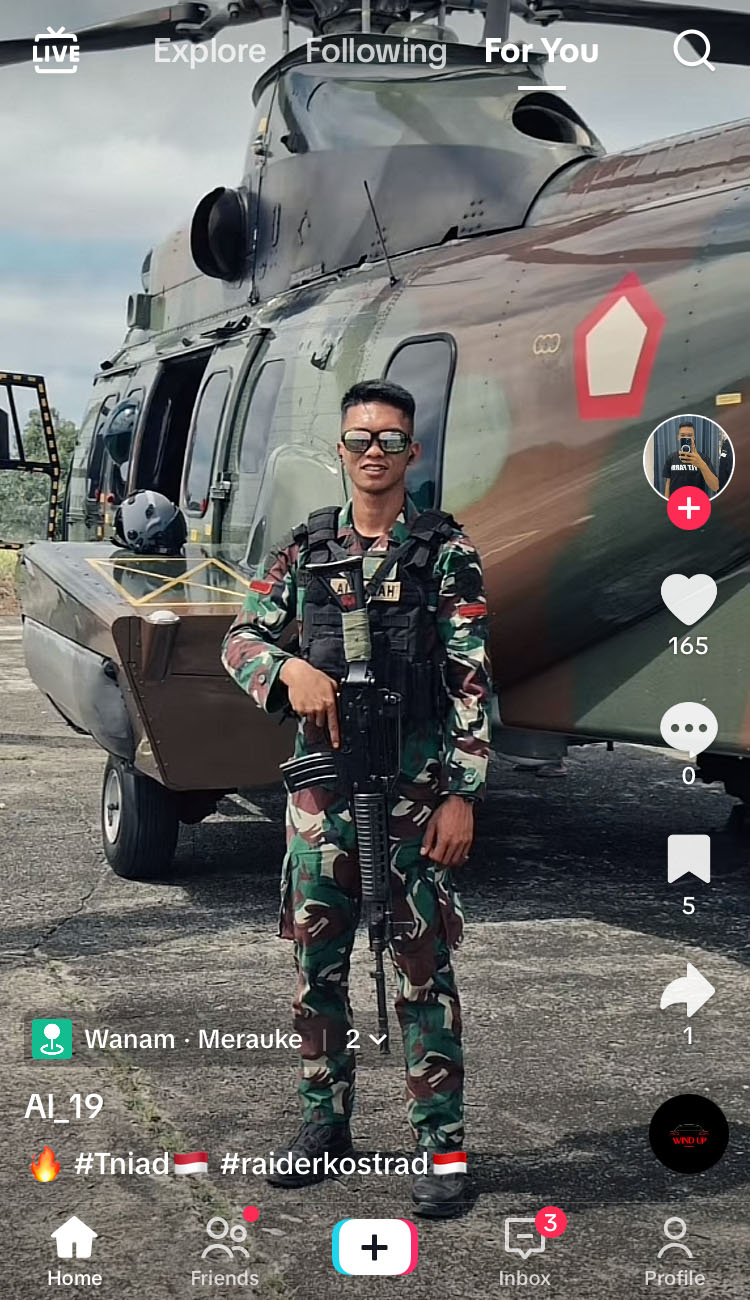

The Gecko Project tracked what happened over those months using two sources: testimony from indigenous Papuans whose land fell under the programme and the TikTok posts of Indonesian soldiers deployed to the area to develop the food estate.

Our research reveals that as early as August, the military deployed an elite combat unit to the programme, whose members have been implicated in extrajudicial killings in recent years. TikTok videos show armed members of this unit patrolling the forest, rivers and villages, and accompanying excavators.

While that unit was on the ground in Papua getting the project underway, thousands of kilometers to the west newly-recruited young Indonesians were undergoing infantry training. By November, five months after signing up, many of these soldiers were on the ground in Papua.

For the Papuans whose land has been targeted, the deployment has generated a climate of fear, suppressing any sense that they can meaningfully object to a programme that could upend their livelihoods. That fear is built on the legacy of decades of state violence in Papua and impunity for the perpetrators. The military has been implicated in the torture and extrajudicial killing of indigenous Papuans.

“It’s like a horror for the community,” said Alfeus Mambes, a man from a village named Wogekel. There, he said, soldiers were stationed at every corner of the village, as if they were in a war zone. “People are not able to speak up for their rights. There are so many people who want to talk, but there is no support because they are afraid of the apparatus. There are too many soldiers.”

The Indonesian government and military did not respond to requests for comment.

‘Every development has its consequences’

Large-scale state agriculture projects have a long and troubled history in Indonesia. Since the mid-1990s, presidents have announced grand government schemes to convert vast areas of forests and community lands into crops. These schemes have repeatedly faltered, leaving a trail of failed crops, deforestation, fires, flooding and conflicts with indigenous communities who object to the annexation of their land.

These failures did not deter then-president Joko Widodo, known as Jokowi, from reviving the idea in 2020, as the pandemic threatened global supply chains. An investigation by The Gecko Project revealed how the Ministry of Defence — assigned a role in overseeing a portion of the food estate programme — forged ahead with hastily-conceived plans to cut down thousands of hectares of forest in Central Kalimantan, Borneo, to plant cassava. Within months, the crops were once again failing.

The ill-fated project received widespread media attention and public criticism. But Jokowi defended the programme and vowed to push ahead with it. By 2023, Minister of Defence Prabowo Subianto was running to replace Jokowi as president and redoubled his support for food estates.

“We must have our own food production,” Prabowo said in a televised interview with journalist Najwa Shihab in June 2023, when pressed on his role in the failed food estate in Central Kalimantan. “How can a country be independent if it cannot feed its people?”

When Najwa remarked that the food estate in Central Kalimantan had harmed the local community, Prabowo said that, “Every development project certainly has its consequences.”

“We have to mitigate and we have to protect the people,” he added.

The government’s plans began to coalesce around southern Papua in the eastern reaches of the country, where coastal savannahs merge into deep tropical rainforests. There, the culture and livelihoods of the Marind, Maklew, Khimaima and Yei indigenous peoples are deeply entwined with forest and ancestral lands. Industrial-scale agriculture has yet to take root to the extent it has on the islands of Borneo and Sumatra, where oil palm and timber plantations stretch for miles on end.

As the plans began to trickle out, it became apparent that the programme had the potential to transform an area half the size of Belgium — 1.6 million hectares stretching from the coast for miles inland, all of which would be used to produce rice and sugarcane.

Researchers warned that the clearance of such a vast area of forest would generate 782.45 million tons of CO₂, blowing a hole in the side of the nation’s climate targets. Anggi Prayoga, a campaigner at the nonprofit Forest Watch Indonesia, said the programme would lead to “massive deforestation.” “[The] food estates are built on natural forests, and established by destroying Papua’s forests,” he said.

The government began taking steps to avoid some of the pitfalls of previous food estate programmes, ensuring it had the full force of the state behind it. The National Food Agency announced that an $8.8 billion budget had been allocated for “food security”; the Papuan food estate was designated a National Strategic Project, streamlining the bureaucratic process; and the military began recruiting soldiers who would soon descend on Papua’s indigenous lands.

These TikTok videos offer a window into how the food estate project has been militarised

In May 2024, the military begins recruiting young men from across the country to form five new special battalions

They undergo training at military bases on the island of Java

By November 2024, the recruits start to arrive in Papua after a five-day journey

Joining hundreds of excavators already sent to the region

The videos show soldiers playing a hands-on role in developing the food estates

In the comments, users share messages of encouragement and pride in the mission

Our reporting indicates a very different experience for indigenous Papuans

#raiders

By the time the new battalions arrived in South Papua, in November, there was already a military presence in the area targeted for the food estate, based on our review of TikTok posts.

Several posts by soldiers’ accounts showed their presence close to a port in the village of Wanam from August 2024 onwards. The same month, hundreds of excavators arrived to be used for land clearing.

The same TikTok accounts showed soldiers patrolling rivers through deforested land and escorting personnel as they operated excavators. The soldiers are often armed, even when patrolling through villages.

Using the posts, The Gecko Project was able to determine these soldiers belonged to two combat units: Battalion 755/Yalet and Battalion 141/AYJP. In several posts, the number “755” was visible on soldiers’ uniforms. The users also included captions and tags in previous posts alluding to their units. Some referred to “Yonif Raider 755/Yalet” and used the hashtag #yonifraider755yalet. Yonif is a portmanteau of the words Batalyon Infanteri — an infantry battalion.

The deployment of Battalion 755 is perhaps unsurprising — the unit was based in Merauke until January. But it also highlights the dangers of deploying combat troops in active service to an agricultural programme: these “raiders” are an elite combat unit, trained in guerilla warfare. Several members of Battalion 755 have been implicated in extrajudicial killings in recent years, while apparently avoiding any serious repercussions.

In 2017, three members of Yonif 755 unlawfully arrested a 23-year-old Papuan man named Isak Dewayekua. Isak was subsequently tortured to death. The three soldiers were arrested and charged, but the case against them was dragged out in the courts and activists alleged that Isak’s family were pressured to drop it.

According to military court archives, the three soldiers were initially sentenced to just a year and eight months in prison, and dismissed from military service. However, they appealed. In the end their sentences were reduced by three months — and they remained in post.

Two years after that case concluded, in 2020, five Yonif 755 personnel attacked the police in Mamberamo Raya, killing three policemen and injuring two others. The motive was unclear; it was said to be due to a misunderstanding. In September 2021, the five perpetrators were sentenced to less than a year in prison and, again, were not discharged from the military.

Made Supriatma, who researches military-government relations at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, said that the participation of combat troops in the food estate programme raised the possibility of violence against Papuan civilians. He noted that Yonif 755 was formed to respond to war situations and that working on an agricultural project was “not part of the military’s job.”

“The army should be in barracks,” he said.

Indigenous lands annexed

Yasinta Moiwend’s first indication of something untoward came in May 2024, when helicopters flew several times over her village in Wanam — an unusual sight.

Yasinta worked to support her family by collecting root crops, cassava, and other plants from her ancestral land, as well as fishing. Three months after the helicopters, excavators arrived. The heavy machinery began leveling the forest and indigenous land in Wanam, including the land she worked on every day.

Yasinta said the people of Wanam were pushed by the military to “consent” to the food estate project. The soldiers approached residents and asked them to support it on the grounds that it was for the good of the community, Yasinta recalled. In September and October, the army distributed rice, instant noodles and cooking oil to Papuans. Yasinta suspected it was an attempt to curry favour.

“We don’t want to accept it,” Yasinta told The Gecko Project. “We don’t eat rice. We grew up with sago, garden plants like yams. We have staple foods, not rice.”

As the soldiers moved in, heavy machinery destroyed and cleared the forest. Yasinta felt helpless. “We have seen that our forests have all been destroyed,” she said. “We are powerless.”

Some 140 kilometers to the east, around the same time, Yoshua Balagaize, a retired civil servant in his early 60s, learned from neighbours in his ancestral village that their land was also part of the programme.

In late August 2024, the community in his village Kaliki held a meeting to discuss their position on the project. Yoshua was resolved to oppose it. “I really don’t want any companies to come in because it’s destructive,” he told The Gecko Project.

But the villagers were to have no say in the project. Just days after the Kaliki meeting, soldiers arrived on the clan’s land and installed wooden stakes, marking it for conversion into rice fields. A soldier told Yoshua their instructions came from the central government, and they were told to “complete it quickly.”

Two of Yoshua’s younger siblings whose job was to guard the land did nothing out of fear of being beaten, he said. They stood silently, watching as the soldiers sunk in their stakes. Soon afterwards, the heavy equipment arrived and began clearing the forests and gardens.

“We can’t fight them,” Yoshua’s brother told him. “We are afraid of being beaten.”

Simon Balagaize, Coordinator of the Malind Anim Kondo-Digoel Indigenous Peoples Forum, a local indigenous group, said that some people had chosen to leave their villages. “I found that some members of three clans, Moiwend, Kahol and Ndiken, chose to live in huts in the forest to hide from the military,” he said.

In late September 2024, Yasinta and other indigenous people protested in front of visiting officials, including the Acting Governor of South Papua and police and military representatives. Yasinta performed a traditional ritual called a duka. She sprinkled her face and body with a white mud to symbolise the feelings of grief she was experiencing.

Yasinta held up a poster saying that the community in Wanam rejected the food estate program. She raised her voice, decrying the damage to nature in the indigenous lands.

Not long after the protest, Yasinta was approached by soldiers.

‘Who made this poster?’

‘We want to meet the person who made the poster.’

They returned repeatedly, pushing Yasinta to accept the food estate, but still she refused. Whenever she prepared to leave the village the soldiers would ask where she was going and what she needed. “We panicked, we were afraid,” she said. “We live here, why are we being questioned?”

A legacy of human rights abuses

The government’s deployment of thousands of soldiers is set against a backdrop of decades of state violence against indigenous Papuans. The military maintains a presence in Papua to suppress a simmering independence movement dating back to a sham ballot that allowed.

Indonesia to acquire the territory in 1969. The independence movement has a military arm, Organisasi Papua Merdeka, or OPM, which is engaged in a low-level armed conflict.

The operation against OPM has repeatedly spilled over into extrajudicial killings of innocent Papuans, according to human rights monitors, along with other rights violations ranging from arbitrary arrests to torture — incidents sometimes documented and shared on social media.

Amnesty International data shows 132 Papuans were allegedly killed at the hands of the authorities between 2018 and 2024. A report by the Indonesian Legal Aid Association documented 44 cases of violence committed by the authorities against Papuans in 2023.

In a recent, high-profile example in February 2024, three Papuans were tortured by 13 soldiers because they were considered to be members of OPM. A video showing soldiers beating one of the men, who later died of his injuries, went viral. The military initially denied the incident had taken place and dismissed the video as a hoax, before finally issuing a public apology. Thirteen soldiers were named as suspects. The Gecko Project was unable to determine whether charges were brought, based on official public records.

The military has also acted to advance the interests of mining, plantation and logging projects in Papua, according to human rights monitors and previous investigations by The Gecko Project. Papuans have expressed fear that if they oppose developments they will be falsely labelled as “OPM,” giving the military cover to arrest them or subject them to violence.

The food estate programme takes this further by formalising the military’s role in a national development project. The approach has been welcomed by the Minister of Agriculture, Amran Sulaiman, on the grounds that it will quickly solve the problem of a lack of manpower. In addition to the new battalions, the army has also opened registration for military officers to focus on agriculture; and established a food brigade, a collaboration between the Ministry of Agriculture, army and the national police force, Polri, intended to help manage rice fields.

Benni Wijaya of the Consortium for Agrarian Reform said that the approach had the effect of sidelining the people who already farmed the land. “By continuing to push for food estates, the government is actually putting food policy in the hands of corporations,” he said. “If the government is really serious about building a food estate, why not encourage it by giving at least one hectare of land to each farmer, as well as through agrarian reform?”

The legal basis for the government’s approach is unclear. The military can be deployed for non-defence purposes, but only with the consent of parliament. “Well, the political policy and decree [that should be the basis for sending soldiers to Papua] has never existed,” said Hussein Ahmad, deputy director of Imparsial, an Indonesian nonprofit that researches human rights issues. “We can say that [sending soldiers to the food estate] is illegal.” The Gecko Project was also unable to find evidence of any discussions related to the deployment of troops to oversee food estates in the official record of the House of Representatives.

Read more reporting from The Gecko Project on Papua and Food Security.

Join The Gecko Project's mailing list to get updates whenever we publish a new investigation.

****

Reporting by Faisal Irfani and Margareth Aritonang.

Photography by Ulet Ifansasti.

Header illustration by Hendra Afrians.

Editing by Tomasz Johnson and Jessica Hatcher-Moore.

Multimedia editing by Katia Patin.