- Leaked documents reveal how a major Indonesian mining firm, Harita Nickel, polluted waters on a tropical island for more than a decade.

- Internal tests showed the pollutant—a toxic carcinogen—reached the drinking water of a local village. But residents were never warned and Harita publicly insisted the water was safe.

- Harita is a linchpin of the global electric vehicle industry, selling to Chinese manufacturers who make batteries for car firms including Tesla, BMW and Toyota.

- This investigation is the result of a collaboration between The Gecko Project, OCCRP, Deutsche Welle, KCIJ Newstapa, and The Guardian, as part of the #ToxicLeak reporting series.

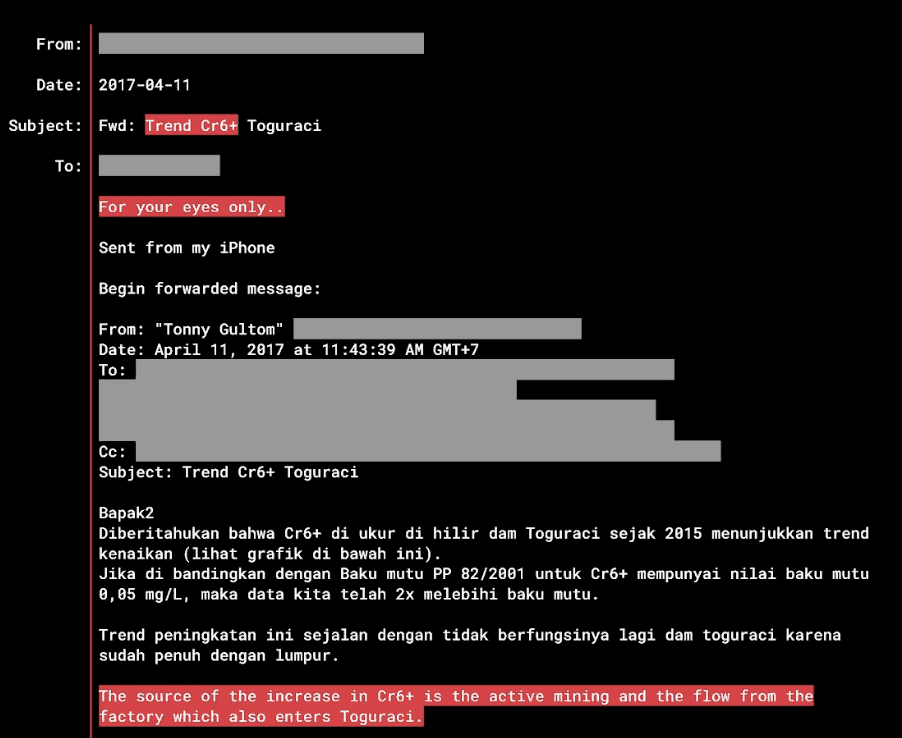

‘For your eyes only’

Tonny Gultom knew that Harita Nickel had a major problem on its hands.

As the executive responsible for environmental compliance at Harita—one of Indonesia's most powerful mining conglomerates—Tonny was charged with ensuring it did not pollute the waters of Kawasi, a village on the western coast of a once serene tropical island, named Obi.

Harita operated a sprawling mine and industrial facility on Obi, where it was digging up vast amounts of ochre-coloured soil each year and refining it to produce nickel. Nickel that could one day end up in the batteries of electric vehicles on the streets of London, Berlin, or Washington.

The residents of Kawasi—fishermen, farmers, families whose lives had long been entwined with the island’s coastline and sago groves—once bathed in the local river that traversed the narrow strip of land between the village and mine. They still drew their drinking water from a spring that lay a few hundred yards from Harita’s operations.

Testing data in Tonny’s inbox revealed that the river contained high levels of hexavalent chromium, or chromium-6, a toxic chemical strictly regulated worldwide to protect unwitting citizens from heightened cancer risks. The chromium levels had been climbing for two years, and one reading showed they were double the legal limit.

Tonny hit forward, sending the data on to a colleague, stating that the “active mine” was the source of the contamination. He, in turn, forwarded it on to another senior executive, prefacing the email with a note of caution: “For your eyes only.”

As Indonesia tightened its grip on the global nickel market, Harita emerged as a pivotal player. The country’s dominance is the result of an aggressive industrial strategy, including a ban on raw nickel exports and heavy investment in domestic processing, much of it backed by Chinese capital.

Harita built Indonesia’s first plant to transform nickel into battery-grade material. A company within the Harita group signed deals with battery manufacturers supplying the world’s major car firms. Harita’s 2023 Initial Public Offering (IPO) was the cherry on the cake, giving it the prestige of a stock exchange listing and generating more than half a billion dollars.

In 2024, Harita Nickel would dig out 6 per cent of the world’s nickel supply from the small island of Obi.

But as smelters and tailing dumps swallowed the land around Kawasi, Tonny and his colleagues faced mounting evidence of Obi’s toxic contamination. An investigation by The Gecko Project, the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, Deutsche Welle, KCIJ NewsTapa and The Guardian, drawing on internal emails and documents, reveals for the first time the true extent of years of pollution in the Kawasi district—and how, eventually, chromium-6 seeped its way down into the village’s main drinking spring.

Harita has issued outright denials that it has polluted the water in Obi publicly, in response to The Guardian newspaper, and privately, in response to banks carrying out due diligence for its IPO. But internal emails show that for more than a decade, the company’s own testing recorded carcinogenic wastewater repeatedly spilling from the facility in the Kawasi area. By 2022, the village’s main spring would be contaminated with high levels of chromium-6.

Five experts—including toxicologists, an epidemiologist and a geochemist—who reviewed a redacted sample of Harita’s spring water and river testing data at the request of The Gecko Project concluded that if the company’s testing was accurate, it showed evidence of chromium-6 levels breaching World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines and legal limits set in Europe, the US and Indonesia.

Two Indonesian environmental lawyers, including a former deputy chairman of Indonesia’s Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK), said the evidence presented strong grounds for criminal prosecution.

Laode M. Syarif, a former KPK commissioner and a lead environmental law trainer at Indonesia’s Supreme Court, said that both Harita and executives within the company could be liable and should be held accountable. “The government must act—whether through civil, administrative, or criminal enforcement under Indonesia’s mining laws,” he said.

Internal emails and monitoring data show that as evidence mounted of rising chromium-6 levels, Harita forged ahead—expanding mining and processing, generating more waste, while aware of the contamination and that its efforts to stem it were falling short.

As global demand for electric vehicles surged, Harita’s diggers tore through the soil on Obi Island. Smelters and refineries roared to life, producing mixed hydroxide precipitate, which is further processed into cobalt sulfate and nickel sulfate—key materials potentially entering the EV supply chains of Tesla, BMW, Toyota, Mercedes-Benz, Volkswagen, General Motors, Ford, Honda, and Volvo.

And the people kept drinking.

“Our water is no longer sterile. But like it or not, we have no choice—we have no other springs,” said Nurhayati Jumadi, a Kawasi resident and mother, who lives in the shadow of Harita’s mines and the vast, billowing chimneys that now dominate her village’s skyline.

‘We need to seriously tackle the Cr6 problem’

Harita began extracting nickel on Obi in 2010 through its subsidiary PT Trimegah Bangun Persada (PT TBP). The business is controlled by billionaire Lim Hariyanto Wijaya Sarwono, who built an empire on gold and palm oil. Obi was his first major foray into nickel—a move that would soon reshape the island.

A mountainous, forested island in the Maluku chain, Obi is just 85 kilometres across at its widest point. It was once a waypoint in the global spice trade, known for its nutmeg, mace, and cloves. It may also hold traces of the earliest human migrations through Indonesia, with evidence suggesting people passed through here on their way to the supercontinent of Sahul more than 50,000 years ago.

Kawasi, once a quiet farming and fishing settlement with a timber industry on the west of the island, would become the epicentre of Harita’s operations. Migrant workers flooded in, drawn by jobs in the mines and processing plants. Today, timber and corrugated iron homes sit in the looming shadow of Harita’s industrial complex, where the machinery hums day and night.

Nickel mining is a destructive process that scars the islands in eastern Indonesia, like Obi, that are home to most of its reserves. Open-pit mines strip away rainforest and soil, exposing the ochre-coloured ore beneath.

Some effects are glaring—the seas near Indonesia’s nickel mines churn thick with brown runoff. Others are less visible, if potentially more insidious, including the potential for contamination by toxic heavy metals such as lead, cadmium, and chromium-6.

Most commonly a by-product of industrial processes, chromium-6 became infamous after tainting the water in Hinkley, California. The case, brought to light by paralegal Erin Brockovich and a film bearing her name, revealed its dangers to the world. Exposure to chromium-6 can wreak havoc on the body, causing liver and kidney damage, teeth erosion, skin irritation, and potentially cancer.

Chromium is also found naturally in soil but can transform into its toxic hexavalent form, chromium-6, when exposed to air and water, a process accelerated by nickel mining. To curb contamination, Indonesian law requires companies to monitor wastewater and groundwater, reporting their findings to regulators. Chromium-6 in drinking water is legally capped at 50 parts per billion (ppb), mirroring WHO guidelines, while mining wastewater must not exceed 100ppb—a limit meant to check industrial pollution at its source.

If pollution levels exceed limits, firms face increased scrutiny and must show they are taking action. Failure to do so can trigger sanctions ranging from fines to the closure of business operations, with prosecution on the table—though rare.

This investigation is based on a review of hundreds of internal Harita documents and emails, in which staff shared and discussed the implications of testing data between 2012 and 2023. The data was analysed by The Gecko Project and OCCRP and supplemented by interviews with experts in mining, chromium-6, Indonesian environmental law, and residents of Kawasi.

Trouble surfaced in Obi within two years. In 2012, Harita’s monitoring revealed that water running off from one of its mines contained chromium-6 at levels three times the legal limit.

The breach was documented in a report which outlined the company’s legal obligations to manage wastewater—controlling runoff resulting from rainfall passing through the open mining areas, stockyards, and waste storage sites. Samples from two points where Harita tested the water leaving its site showed total chromium-6 concentrations of 350 parts per billion (ppb) and 130 ppb—both exceeding the legal threshold of 100 ppb.

The task of mitigating the contamination ultimately fell to Tonny Gultom, Harita’s director and head of Health, Safety, and Environment. With a foot in both the boardroom—as a director of Harita—and the mine, he balanced corporate strategy with on-the-ground realities. A veteran of Indonesia’s mining sector, he holds post-graduate qualifications in hydrology and financial management. Internal communications show he repeatedly pushed for compliance with environmental regulations.

By 2014, Tonny was concerned the pollution could lead to a black rating from the environment ministry. Companies with such a rating face enforcement actions, including fines, legal proceedings, or even shutdowns.

Testing data was repeatedly showing chromium-6 at above legal limits. Tonny urged staff to “make a higher effort” to bring the numbers down. “I still see too many non-compliant values from Cr6 [chromium-6] at all compliance points,” he warned a colleague in an email in February 2014.

His colleague, a regional environment manager, responded that the levels remained high because “there have been no changes that can directly reduce Cr6.” Tonny forwarded the exchange to three senior managers, emphasising that the levels had been persistently high throughout 2013, and raising concern it could be inferred from this that they had made “no effort” to address it.

Harita sought to contain the pollution by building settling ponds to slow the flow of water in and out of the mining site. They began adding ferrous sulfate to wastewater, a chemical fix aimed at bringing down chromium-6 levels.

That year, testing showed chromium-6 above legal limits in community farmland. A regional manager acknowledged in an email that it had come from “an area disturbed by mining”. Harita appeared to take steps to keep the people of Kawasi in the dark. The manager wrote to Tonny and other senior managers, saying he had asked a government official to “delay” informing the community of the contamination “due to the current non-conducive situation.”

Whether or not this became company policy, it was an approach that apparently prevailed. Villagers interviewed by The Gecko Project in 2025 said they were never told about water contamination by Harita.

“There was no notification from the company,” said Nurhayati. “Especially not to inform us that, ‘Residents, our water has been polluted.’ There was none at all.”

Tonny was well aware of the risks of failure. A 2015 academic paper that he co-authored examined the impact of chromium and nickel on plant life on Obi. The paper noted that chromium-6 could be “extremely toxic to plants, animals and humans” and that as well as being carcinogenic, it had been “causally linked to liver and bone damage/disease in humans, and the blocking of functional groups of vital enzymes.”

But by 2016, the problem persisted. That year, Tonny fired off an email to environmental compliance staff with a note of caution: “This is why we need to seriously tackle the Cr6 problem.” Attached was a report from a Harita geologist detailing chromium’s presence in Obi’s nickel deposits and how mining could convert it into its more toxic hexavalent form.

The report concluded with the risks it posed to public health: how chromium-6 dissolves easily in water, penetrates cell membranes, and accumulates in the body. Exposure, it warned, could lead to skin irritation, gastric issues, lung cancer, and affect fetal development.

Internal emails repeatedly identified Harita’s operations as the cause of the contamination, as rainwater flowed across land that had been disturbed by mining and flooded downstream. In an email in April 2017, for example, Tonny wrote that “[t]he source of the increase in Cr6+ is the active mining and the flow from the factory that also enters Tuguraci [river].” He proposed repairing and raising the height of a dam on the river, that was then “full of mud”, to enable it to function as a “settling pond”. He described this as “critical” but noted there was “no action yet”.

In 2018, Harita’s staff recorded one of the highest levels of total chromium—a combined reading of both safe and toxic chromium compounds—in wastewater discharged from the mining site. The readings were taken from one of the ponds designed to contain and neutralise the chromium.

Shortly after, Tonny emailed PT TBP’s General Manager, Younsel Roos, with a warning. If the results were reported to the Ministry of Environment and Forestry, Harita would be subjected to heightened scrutiny and possible sanctions. "If we report this… we will be included in the red list of companies that will be supervised (in this case by the Director General of Law Enforcement)," Tonny wrote. "Please help us, sir, so that we can discuss this in the field and how to manage this mine water."

Activist groups in Indonesia were also paying close attention to the environmental impacts of the nickel industry. Tonny grew concerned they might discover the pollution in Obi. In 2018, he admitted he was “worried that if there are NGOs taking water samples downstream, the two parameters above [one being chromium-6] will be easily detected.”

The internal communications over this period do not show how consistently the levels of chromium-6 exceeded legal limits. But it does reveal that it was a recurring problem that persisted for years and that Tonny Gultom repeatedly expressed consternation at the company’s inability to definitively address it.

Harita’s emails also suggest a desire to hide the scale of the contamination—asking officials to withhold information from Kawasi residents, and remaining wary of activist scrutiny. The greatest danger the company faced was reputational damage or sanctions. For the people of Kawasi, by contrast, the danger was chromium-6 seeping into their drinking water, and the litany of potential health consequences.

While the chemical had been flowing out of the mining site since at least 2012, by 2018, it had not yet been detected in the natural spring that many villagers relied on for bathing, cooking, and drinking. But the risk was always looming. The water source—known locally as Air Terjun and referred to in Harita’s internal communications as Kawasi Spring—sat just a few hundred metres from the mining site.

In 2018, Harita commissioned a hydrogeological study of the spring. It included a prescient warning about the potential consequences of failing to take preventive measures: "It is feared that PT TBP's mine development plan could disrupt the existence of Kawasi Spring."

The chromium cover-up

By the time concerns were raised over the potential impact on Kawasi Spring, global demand for Obi Island’s processed nickel was growing rapidly, catalysed by the booming market for electric vehicles powered by lithium-ion batteries.

Indonesia bet big, closing off exports for unprocessed nickel, incentivising foreign investment, and loosening regulations. The gambit was to take a large—even the largest—slice of a global market that could only grow as the world turned to clean energy.

To succeed, investors would need to refine the region’s abundant low-grade laterite nickel into the high-purity material needed for electric vehicle batteries. They turned to a technology untested in Indonesia: High Pressure Acid Leaching, or HPAL. It was a method fraught with risk. HPAL projects elsewhere required massive investment, experienced expensive overruns, took years to get to capacity, and were difficult to operate.

In 2018, Harita broke ground on Indonesia’s first HPAL plant, a $1 billion joint venture with Chinese metals giant Ningbo Lygend. Operated under the company PT Halmahera Persada Lygend, the project marked a significant milestone for Indonesia’s ambitions. “If it comes online successfully,” the International Energy Agency wrote in a report, “other projects could follow.”

Success would create a collateral problem: vast volumes of additional waste, that could potentially compound the contamination on Obi. Warnings emerged before the plant was even operational. In August 2020, a compliance officer flagged persistent chromium-6 contamination across the site. “Cr6+ has always been high due to the influence of the slag storage area, mine yard area, and now the HPAL project opening area,” he wrote in a report to senior Harita employees.

The plant came online in mid-2021, with Tonny Gultom serving as a director of the joint venture. Satellite imagery hints at the impacts on Kawasi. In 2018, the nearest industrial structure stood 1,300 metres from the village, with the open-pit mine creeping toward its northeastern edge. By 2021, Kawasi was encircled by a vast industrial sprawl, whose outer limits lay just 200 metres from the village spring.

Still, for Harita and Lygend, the bet on HPAL was paying off. As production ramped up, the company was securing deals that would link it, indirectly, to some of the world’s biggest automakers.

How Harita Nickel connects to global car firms

PT Halmahera Persada Lygend, the joint-venture between Harita and Lygend Resources & Technology, signed offtake agreements—commitments guaranteeing future sales—with Chinese battery material giants GEM Co. and Jiangsu Easpring Material Technology Co., while also supplying CNGR Advanced Material Co., Huayou Cobalt, and indirectly, CATL.These Chinese companies refine nickel into cathode materials—the positively charged electrodes in lithium-ion batteries that store and release energy.These materials are then likely to be found in the batteries powering global car brands. Among them: BMW, General Motors, Volkswagen, Tesla, and Volvo.

Electric vehicle battery manufacturers GEM Co., Jiangsu Easpring Material Technology Co. and Huayou Cobalt did not respond to repeated requests for comment. CATL stated that it “does not have direct business relations with Harita Group,” is committed to building a globally responsible mineral supply chain and “opposes and prohibits any forms of practices that endanger public health and the environment in the operations of CATL and [its] suppliers.” CATL’s full response can be found at the end of the article, together with all responses received from companies and individuals from whom we sought comment.

CNGR Advanced Material Co., said that it is “currently conducting a comprehensive internal investigation” and will issue a statement by May 2nd 2025.

Within a year of the facility opening, Harita’s reports show it generated $1 billion in revenue. But as Harita anchored itself firmly within the EV supply chain, it was no closer to solving the contamination.

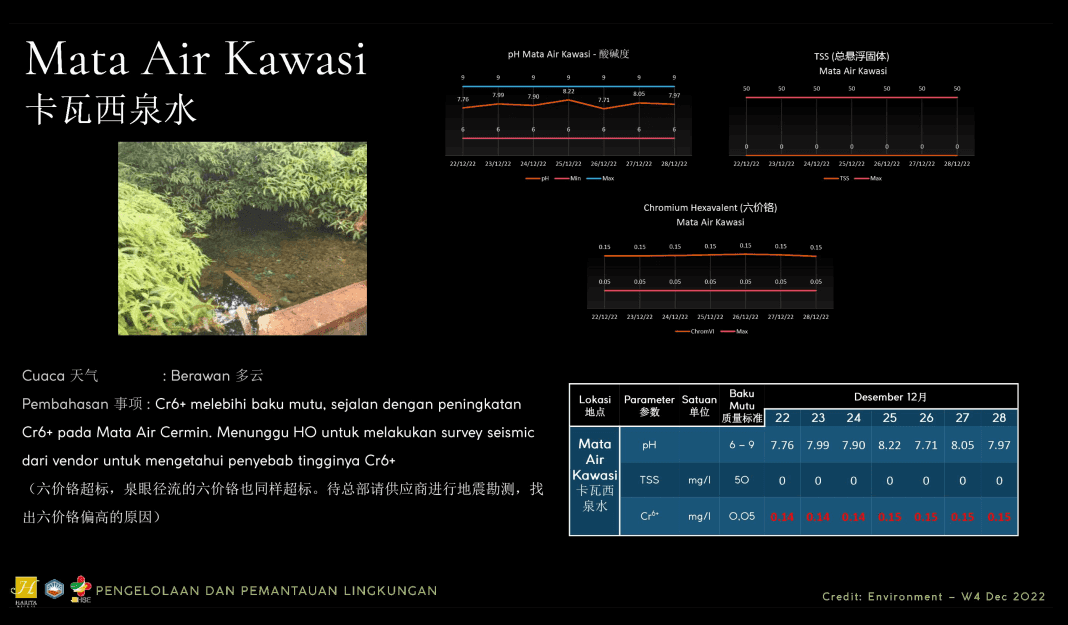

From February 2022, internal testing by PT Halmahera Persada Lygend—of which Tonny Gultom was also a director—revealed that the chromium-6 had finally reached Kawasi Spring. Over the course of 2022 and the start of 2023, Harita was tracking chromium-6 levels closely and circulating the results within the group in weekly environmental reports. Throughout 2022, these reports would show the company repeatedly breached legal and safe limits across the site: drainage outlets, the estuary of Tuguraci River, and the spring providing the village with drinking water.

The reports repeatedly attributed the contamination to Harita’s mining operations. In July 2022, for example, a PT Halmahera Persada Lygend staffer sent a report to an environmental and compliance manager at Harita Nickel. “There is an issue of pollution around the Harita Nickel Obi site area due to the activities of the nickel ore mining, processing, and refining plant,” they wrote.

By February 2022, it appeared Harita and PT Halmahera Persada Lygend would no longer be able to suppress evidence of the contamination. That month, the Guardian published an article revealing chromium-6 levels in Kawasi Spring exceeding legal limits, based on independent testing it had commissioned. It was the scenario Tonny had been concerned about in 2018.

But PT Halmahera Persada Lygend repudiated the findings. In its response to the Guardian, the company stated that tests at the spring conducted between 2013 and 2021 showed compliance with government water quality standards, with chromium-6 levels ranging from 5 to 40 ppb. It also claimed that its monitoring had found no chromium-6 discharge from its system and no impact on Kawasi Spring’s water quality.

The company’s public stance was firm. Behind closed doors, the evidence told a different story.

Harita had repeatedly detected chromium-6 above legal limits in the district of Kawasi for close to a decade. Just two days before The Guardian’s article was published, internal testing detected chromium-6 at 128 ppb in Kawasi Spring—more than double Indonesia’s legal limit of 50 ppb.

The stakes for Harita had never been higher. Demand for processed nickel from its HPAL facility was surging, and its joint venture with Lygend Resources & Technology was inking deals with major battery manufacturers. But there was something even bigger on the horizon. By 2022, Harita was preparing to list PT TBP, its nickel subsidiary, on the Indonesia Stock Exchange.

The Initial Public Offering (IPO) could generate hundreds of millions of dollars for Harita. But the process involved more scrutiny than it had been subjected to until now. The banks underwriting the IPO were conducting due diligence, as Harita’s own tests were repeatedly showing chromium-6 levels far higher than legal limits.

At the beginning of August 2022, Harita launched an internal investigation to monitor contamination across the group’s facilities and trace its sources. A document outlining the rationale for the investigation made clear the view that whatever the specific source, Harita was responsible, attributing pollution to “the nickel ore mining, processing, and refining plant.”

Over 30 days of testing that month, chromium-6 levels at Kawasi Spring breached Indonesia’s limit of 50 ppb every single day. The crisis wasn’t an isolated incident or a temporary fluctuation—it was a persistent, ongoing contamination event.

The investigation team concluded that contaminated groundwater was polluting the spring with chromium-6, and the Tuguraci river was being contaminated by runoff from Harita’s mine, smelters and HPAL facility. One report noted that some of the chromium-6 levels were “unsafe”. In response, the company proposed further studies and mitigation measures.

As Harita’s internal team confronted the scale of the contamination, consultants working for the banks were scrutinising from the outside.

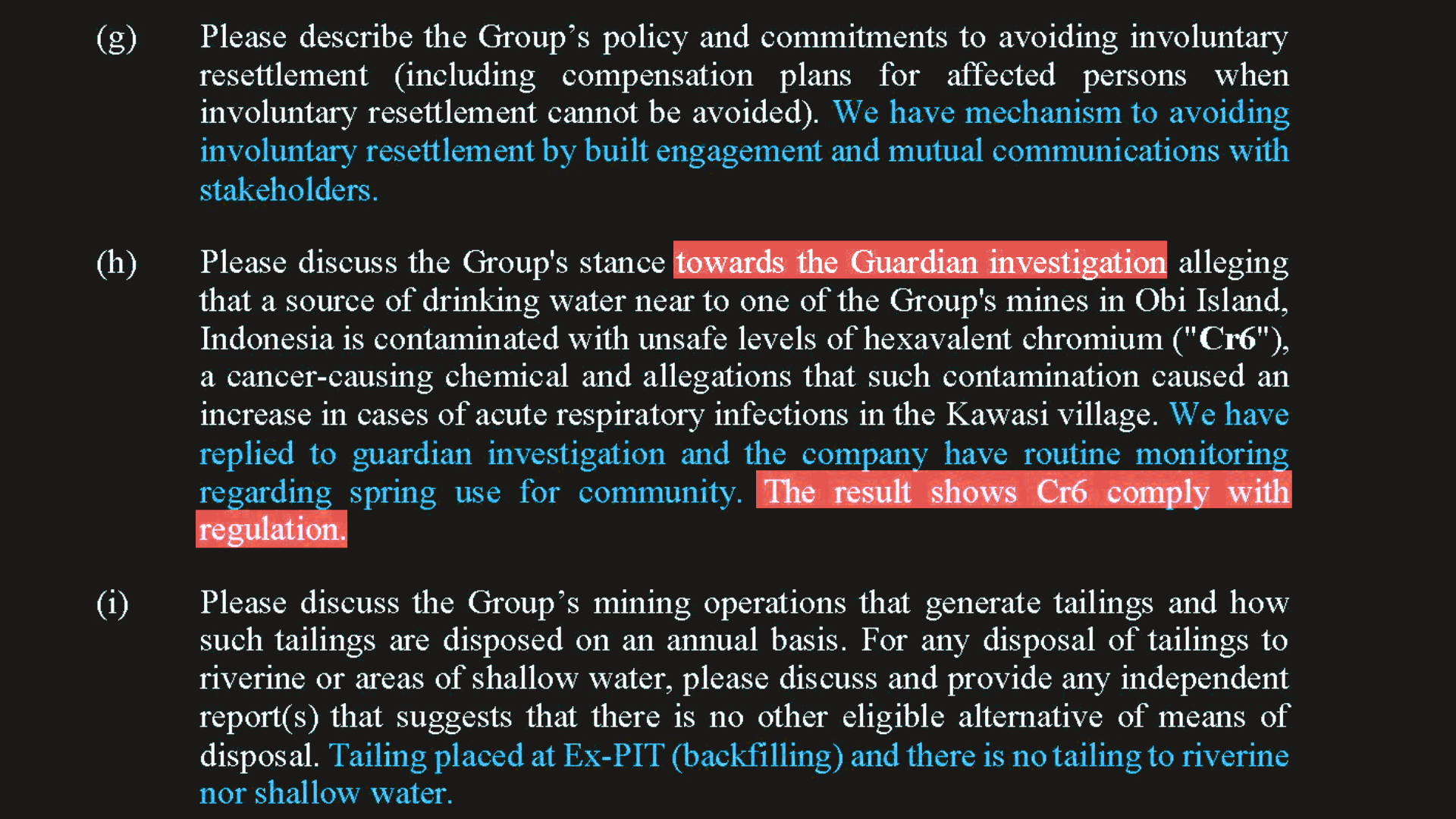

In August 2022, Harita responded to written questions from an international law firm advising the banks involved in the IPO. Harita was asked to comment on the Guardian’s allegations that Obi was contaminated “with unsafe levels of hexavalent chromium”. “We have replied to guardian investigation and the company have routine monitoring regarding spring use for community [sic]”, Harita wrote. “The result shows Cr6 comply with regulation.”

That statement is inconsistent with months of Harita’s testing data. It appears to be refuted by another report, circulated within Harita, just days later, stating that the spring exhibited "high" chromium-6 levels. It acknowledged that contamination in and around Kawasi stemmed from its own operations, citing “MSP runoff”—wastewater from one of its smelters—and “HPAL drainage”—the facility refining nickel and cobalt for EV batteries.

Repeated requests for comment were sent to all banks underwriting Harita Nickel’s IPO — BNP Paribas, Credit Suisse, Mandiri Sekuritas, DBS Vickers, and OCBC Sekuritas. None responded. Only Citigroup acknowledged the inquiry, stating that it does not comment on specific clients, projects or transactions out of respect for client confidentiality. There is no suggestion of wrongdoing by these banks in relation to any investment in Harita Nickel.

In February 2023, Harita internally recorded a chromium-6 reading of 173 ppb—the highest level yet recorded, and more than three times the legal threshold. The internal communications to which The Gecko Project and OCCRP have access end at this point.

Whatever happened next, it did not stymie Harita’s march towards the IPO, or its bullish external position on the pollution levels in Kawasi.

In April 2023, Tonny stood before a group of journalists, lifted a cup of water from Kawasi Spring to his lips and declared it safe to drink. The timing was no coincidence. Days later, Harita Nickel’s IPO launched. With the contamination under wraps, the offering was a resounding success, raising $660 million—one of Indonesia’s largest IPOs that year.

‘We drink it every day’

For generations, life in Kawasi was shaped by the land, the rivers, and the sea. Then Harita came.

“My grandfather had a cashew tree garden at the waterfall,” said Nurhayati. “If he was thirsty, he didn’t bother carrying water.” He would drink straight from the river. Something unthinkable now.

Before the mines arrived, Nurhayati had drunk from the Toduku River, which winds through the village, “since I was in my mother’s womb. Because my mother drank water from Toduku, so I drank from it too.”

That Kawasi is gone.

Behind her home, a small wooden structure with a cement floor, Harita’s chimneys churn thick plumes of smoke into the sky, staining it a sickly yellow. The air is heavy with dust. It clings to skin, burrows into lungs.

Nurhayati’s own body bears the cost. “When I cough, there is pus and blood,” she said. Stomach cramps and diarrhoea are frequent. “We don’t know if it’s the water. But we drink it every day.”

Obi Island is small. Kawasi, smaller still. Reaching it requires flights and two boat journeys—more than enough time for word to spread of an outsider’s arrival. Those who aren’t itinerant workers stand out, and the company watches closely. In the dusty village streets, security is ever-present: private guards, police, soldiers.

This is a National Strategic Project. That designation typically brings military protection and tightens control over who gets in and what they see. Journalists have been stopped and ejected. Outside of company-supervised tours, access is tightly controlled.

Sanusi, a fisherman from Kawasi, remembers when the river ran clear, when villagers could drink from it without fear. Now, he says, it surges into their homes whenever “the company’s embankment breaks.”

“It fills up the residents’ houses.”

On his phone, he pulls up footage: thick, red flood water bursts into homes, rising against walls.

Like many in Kawasi, Nurhayati and her child suffer from raw, reddened skin, persistent rashes, and incessant itching.

Children, she said, had died. “My nephew had diarrhoea for a week. He didn’t survive.”

A direct link can be drawn between elevated levels of chromium-6 and increased risks of adverse health effects and cancer. But proving that the contamination—or any single pollutant—is the cause of illness is far more difficult.

Still, in Kawasi, sickness is an inescapable reality. Villagers insist it has worsened since nickel mining and smelting arrived on their doorstep. Itchy skin, diarrhoea and persistent coughing are a fact of life.

Harita has itself acknowledged the risks. An internal 2016 company document on chromium in nickel deposits noted that “there is a potential for health disorders due to Cr6+, such as skin irritation, intestinal and gastric irritation, and an increased risk of lung cancer.”

Three villagers told our reporter that they still use water from the spring for bathing, cooking, and drinking. A further eight said they use it to bathe and cook but now buy bottled water, fearing contamination.

Not one of the villagers we interviewed had ever been informed by Harita of water contamination in the spring, river, or surrounding land. None had been provided with alternative water sources by either the company or the regional government.

Mann Noho, a sinewy, stoic man who once worked for Harita, stood by the pipes that funnel spring water to the village. Beyond the thicket, Kawasi Spring is now fenced off, guarded by CCTV and high metal barriers. He traced a finger along the rickety white pipes leading from the spring to people’s homes, describing the changes. The taste was strange, the colour off. “For those who have money, they buy bottled water,” he said. “For people like me, we have no choice but to use that water.”

His four children suffer from relentless stomach cramps. “We know the water is contaminated,” he said. “But this company doesn't drink the water, so they have no idea how sick it makes them feel.” Many suspect the water is polluted, but they have no proof—only its taste, colour, and smell.

Christopher Banks, a toxicologist who reviewed some of Harita’s testing data at the request of The Gecko Project, wrote that it was hard to draw firm conclusions about the level of risk without more information about how testing had been undertaken, but that it showed “considerable contamination”.

He noted that not everyone exposed to chromium-6 would suffer health problems, but that it did increase the risk of developing cancer. He wrote that pregnant women could face “unique risks” and that “infants and children are generally more susceptible than adults to carcinogens and other toxicants, so cancer risk from Cr(VI) exposure would be elevated in these subpopulations.”

Professor Ignasius Sutapa, Vice Chairman of the Indonesian Ministry of Health’s Committee for Environmental Health Experts, reviewed some of the data—without being informed of the identity of the company—and warned that chromium-6 contamination poses a serious threat to public health in Indonesia. “This data makes it clear—we must act to protect our water sources,” he said.

The contamination isn’t just a public health issue. It may also be a legal one.

Laode, the former anti-corruption commissioner, said Harita’s internal documents could form the basis for administrative, civil, or even criminal prosecution. “Activists and journalists have long reported water pollution from nickel mines,” he said. “But this—internal company data—proves violations of Indonesian environmental law.”

After being shown data by The Gecko Project, Fajri Fadhillah, a researcher at the Indonesian Center for Environmental Law, said the evidence suggests Harita executives had been aware of the contamination for years. “This eliminates any plausible deniability,” he said. “This case presents a rare opportunity to enforce environmental law.”

Harita Nickel, Lygend Resources & Technology, Tonny Gultom, and Younsel Roos did not respond to The Gecko Project despite repeated requests for comment. The week after we wrote to Harita, the company posted an article to its website titled “Kawasi Spring Preserved, Residents: Clean Water is at Hand”. The article said that Harita conducts “periodic monitoring” of the spring and that its latest results showed it was safe to drink, with “very low levels” of chromium-6.

Mercedes-Benz stated that while it does not source Nickel directly, it maps its Nickel supply chains in detail and cited the disposal of toxic tailings from HPAL processing facilities as a relevant topic. Further, it stated that in response to allegations of water pollution on Obi Island in 2022 it appointed a supply-chain auditing company to inspect Halmahera Persada Lygend and received reports of “solid results”. It added that Harita Nickel will conduct an audit based on the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance in the upcoming weeks.

Toyota said that it values the principle of “respect for humanity” and expects its suppliers to uphold human rights and avoid any violations, in line with the company’s global policies.

Tesla, BMW, Volkswagen, General Motors, Ford, Honda, and Volvo, did not respond to The Gecko Project’s request for comment. Click here to read responses from all companies and individuals from whom we sought comment.

Reporting by Alon Aviram, Eli Moskowitz (OCCRP), and a journalist reporting from Indonesia (name withheld).

Editing by Tomasz Johnson.

Fact-checking by Tom Walker.

Multimedia editing by Katia Patin.

Do you have information related to this story that you would like to share? Contact us.

Read more reporting from The Gecko Project on critical minerals and corporate accountability.

Join The Gecko Project's mailing list to get updates whenever we publish a new investigation.