Arkani, an elderly Dayak man, drew a telling comparison between the plight of his community and that of the orangutans inhabiting a nearby rainforest, in a part of Borneo that has been subject to some of the worst excesses of Indonesia’s palm oil boom.

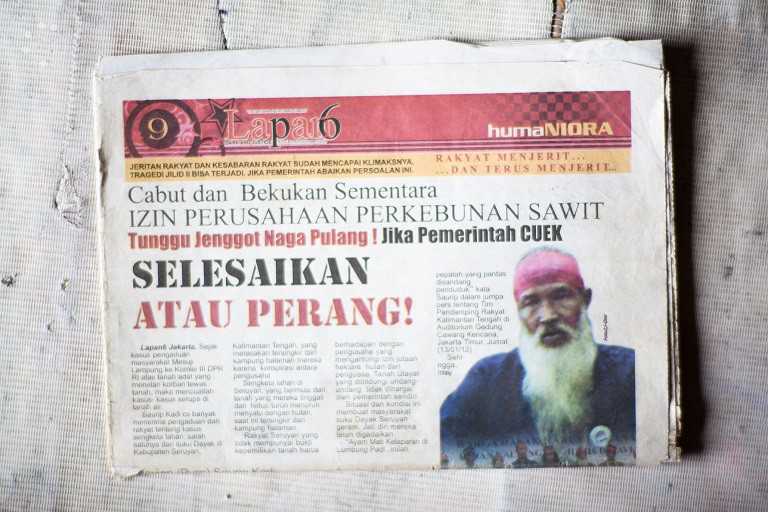

“Orangutans and other creatures were driven from their homes,” said Arkani, who also goes by the name Jenggot Naga — Dragon Beard. “It’s the same with people. We’ve run out of places to live.”

We met Arkani during the reporting for “The making of a palm oil fiefdom,” our investigation into a flurry of plantation licenses handed out by Darwan Ali, the former bupati, or head, of Indonesia’s Seruyan district. Darwan had been reported to the nation’s antigraft agency over permits he had issued to shell companies formed by his relatives and cronies, but he was never prosecuted. We sought to uncover the true nature of the scheme, and chronicle its effect on Seruyan’s people and environment.

Arkani lived in Hanau subdistrict, one of the areas most affected by Darwan’s licensing spree. His small wooden house sat on a dirt road near Tanjung Puting National Park, home to one of the largest and most concentrated populations of Bornean orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus) left in the wild. As bupati, Darwan had ceded huge swaths of land overlapping with the park to BEST Group, owned by a pair of wealthy brothers from Indonesia. Both the central and provincial governments had pressed Darwan to revoke the permits, but he had stood firm, arguing that local people wanted to work in palm oil.

BEST not only cleaved off a chunk of Tanjung Puting’s rainforest; it also cleared farmland claimed by Arkani and his neighbors. And it drained peat swamps to make way for its plantations, rendering the soil prone to burning. And that’s exactly what the peat soil did, with Seruyan falling prey on multiple occasions to the fires and haze that strike Indonesia almost every year.

Arkani was one of those who initially placed their faith in Darwan, when he stood for district chief in 2003. Darwan had been viewed as a putra daerah, or “son of the soil,” a Seruyan native who would fight for his people. But Arkani quickly grew disenchanted with the bupati. “The truth is he tricked us,” Arkani said. “We gave him our trust, but in the end we were forgotten.”

Watch our short film about Arkani, below, to find out more. And then read our investigation into Darwan’s licenses, in English or Bahasa Indonesia.