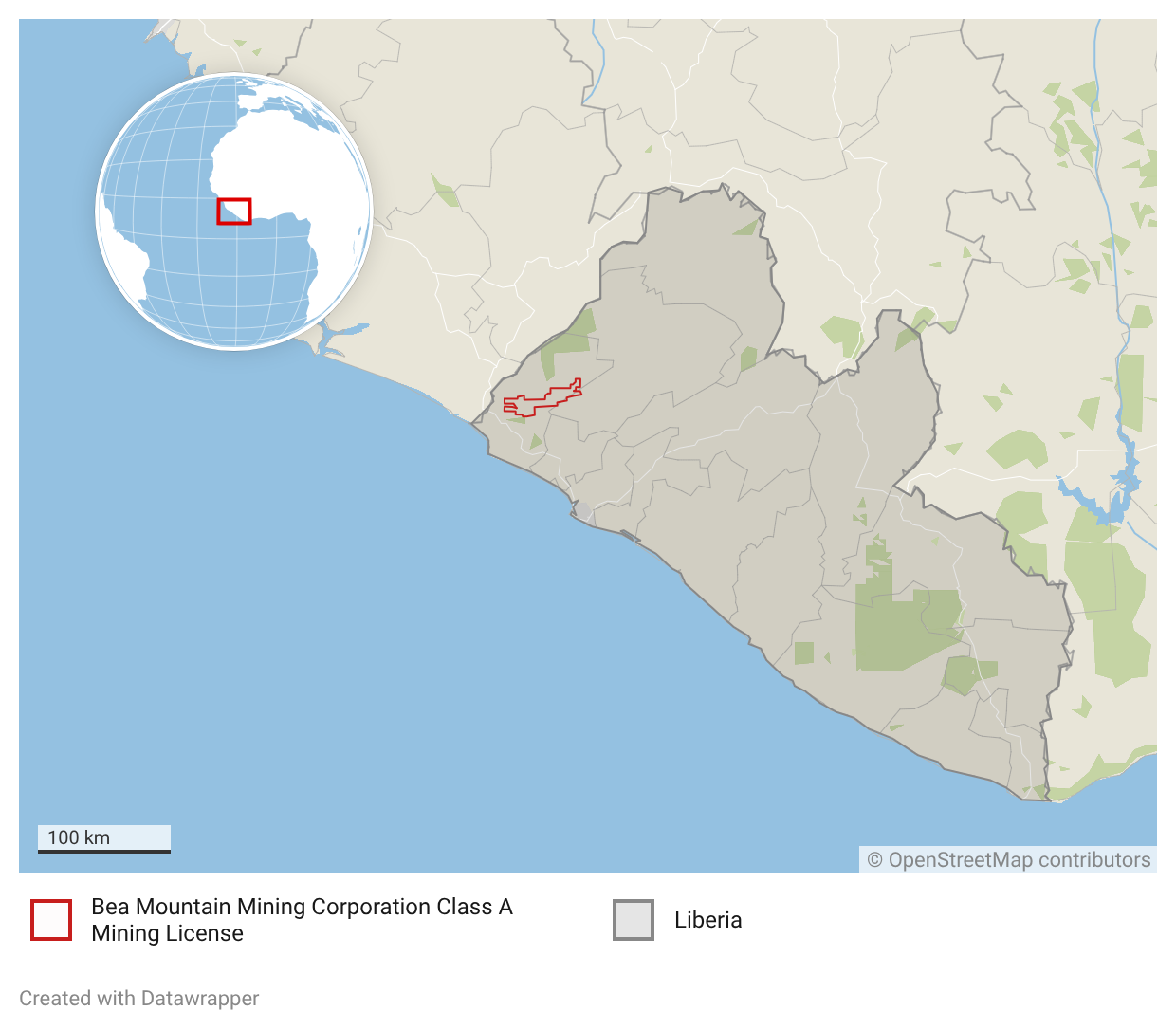

- Liberia’s largest gold miner repeatedly polluted rivers relied on by communities, releasing cyanide, arsenic and copper at levels that killed fish and posed risks to human health, according to government reports and experts.

- Consultants repeatedly warned of contamination risks. But officials and a company insider said the miner operated substandard waste-containment facilities.

- Regulators recorded multiple violations between 2016 and 2023, including illegal discharges, delayed spill notifications and obstruction of inspectors. But the company was instructed to pay just one fine of $25,000.

- Gold from the mine is sold to Swiss refiner MKS PAMP, which is in the supply chain of major technology companies including Nvidia and Apple.

- This article is part of a series on the disappearing forests of West Africa, funded by the Pulitzer Center.

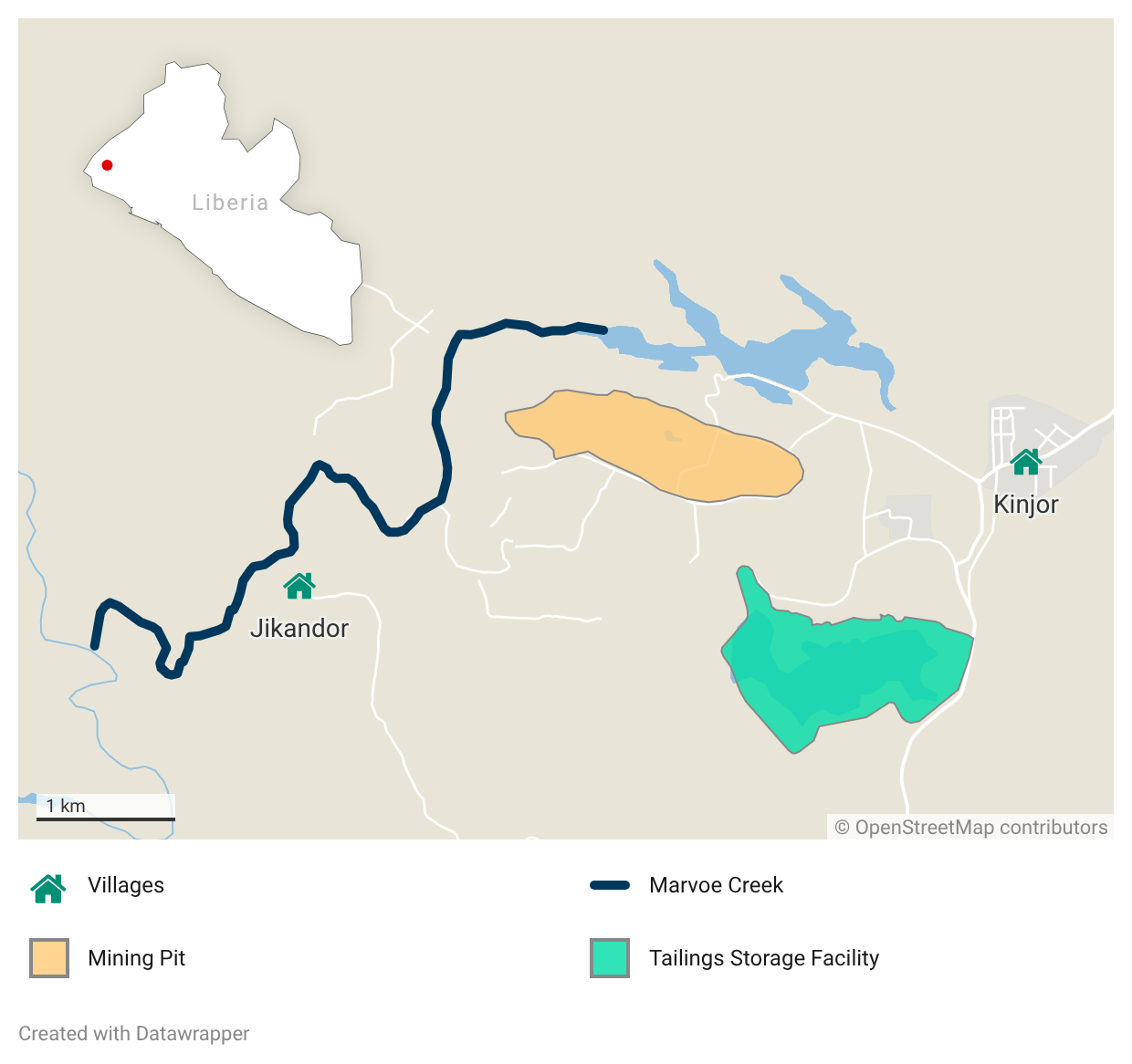

In remote western Liberia, the village of Jikandor sits on the Marvoe Creek, its homes scattered among dense rainforest. For generations, families fished, farmed and drank from the river. Now, they’re preparing to move away — a decision driven by grim calculation.

“The chemical forces us to move,” said village chief Mustapha Pabai, standing in the communal “palaver hut” where village meetings take place, a short walk from the riverbank. “If we don’t move, we will die.”

Pollution from the nearby Bea Mountain Mining Corporation, Liberia’s largest gold miner, has repeatedly poisoned the waterways that pass by Jikandor. Families now drink rainwater or buy bottled water and pay for fish they once caught for free. They have grown used to the warning signs — when dead fish float to the surface, they know another toxic leak has come from upstream, sometimes before the authorities do.

Interviews with residents, experts, government officials and former workers at the company — along with multiple reports from Liberia’s Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) — show that Bea Mountain operated substandard facilities, despite being warned repeatedly of the risks of pollution.

The repeated pollution incidents pointed to failures in corporate responsibility that “can only be described as sustained negligence,” said Mandy Olsgard, a Canadian toxicologist who reviewed the evidence obtained during this investigation.

Cyanide, arsenic and copper spilled at levels above legal limits. Bea Mountain failed to alert regulators on time after a spill and blocked inspectors as they tried to access the company’s laboratory and view test results.

“Even several months of contamination would be alarming enough,” said Dr Jonathan Paul, an earth scientist at Royal Holloway, University of London. “The fact that this has gone on for several years raises serious concerns.”

The spills contaminated an ecosystem home to rare species like the African dwarf crocodile, hornbills, and the endangered western chimpanzee. Of the 17 fish species found near the mine, three are already considered under threat. Multiple villagers reported seeing dead and dying fish floating down the river, after a pollution incident confirmed by the EPA.

“Cyanide water runs into the smaller river and contaminates the bigger one,” said a former company worker, who spoke on condition of anonymity, because they were concerned about professional repercussions. “I saw so much pollution when I was there.”

They described a spill in July 2018, when dead fish floated to the surface after the river was contaminated. The problem could have been fixed, they said, but the company wanted to keep costs down and was not pressured to act. “We need force — from the government,” they added.

Bea Mountain is today owned by Murathan Günal, the son of Turkish billionaire Mehmet Nazif Günal. The elder Günal is one of the so-called “Gang of Five” businessmen who have won numerous contracts under Turkish strongman Recep Erdoğan, through his Mapa Group.

Control of Bea Mountain, which the Günals acquired in 2016, is routed through companies in the British Virgin Islands and Jersey. Neither Bea Mountain nor Mapa Group responded to repeated requests for comment.

The miner’s gold is bought by Swiss trader MKS PAMP, whose refined gold then enters the supply chains of major global technology companies, including Nvidia and Apple.

A spokesperson for Nvidia said the company remains committed to ensuring its “products are sourced responsibly,” adding that it routinely evaluates suppliers against its responsible minerals standards. The company said it relies on independent auditors to carry out due diligence on suppliers and noted that MKS PAMP had been subject to a recent audit.

Apple did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

MKS PAMP said it is committed to responsible sourcing and will continue to monitor the mine.

About the series: West Africa’s Disappearing Rainforests

This investigation is part of a series on West Africa’s disappearing rainforests by The Gecko Project and The Associated Press, funded by the Pulitzer Center. While the Amazon, Indonesia and Congo Basin are frequently covered by journalists and nonprofits, West African rainforests remain overlooked.

A century ago, the Upper Guinean Forest stretched across 216,000 square kilometers of this region — an area the size of Utah. But much has since been destroyed and forest loss has risen sharply in recent years. Home to species like African forest elephants and chimpanzees, it is recognised as one of the world’s most threatened forest systems and a global conservation priority.

This series explores evidence that politicians and officials in Ghana, Liberia and Sierra Leone are working to undermine what protections remain, opening up fragile ecosystems for mining and luxury developments at the expense of rural communities.

Gold mining is a dirty business. Extracting gold from ore often involves cyanide, better known for its role in spy thrillers. The chemical is supposed to be contained and treated before it enters the tailings dam — a storage site for mining waste — and the environment. Mining can also release toxic metals such as arsenic and copper from the surrounding rock, posing serious health risks if not properly managed.

In 2001, Bea Mountain signed an agreement with the Liberian government, later renegotiated in 2013. The agreement acknowledged the risk of “pollution, contamination or damage resulting from operations.”

Over the years, Bea Mountain’s owners were warned of the risks of contamination entering the environment, and advised by mining consultancies to implement strong safeguards. In 2012, four years before the company was acquired by the Günal family, Golder Associates, a Canadian consultancy, found there was a risk of contamination of local rivers from the dam holding the mine’s waste. Seepage would breach Liberian drinking water standards, it warned.

Two years later, another consultancy flagged cyanide and arsenic as key risks. It set out strict measures to prevent contamination, and to ensure that water in Jikandor met World Health Organization (WHO) standards.

Then in 2015, just a year before the Günals acquired the mine and production began, an assessment by an international mining and exploration consultancy again warned that arsenic could exceed WHO standards, threatening local water and wildlife.

The International Finance Corporation (IFC) paid $19.2 million for an equity stake in the parent company of Bea Mountain Mining Corporation in 2014, increasing its holding in 2015.

Bea Mountain had pledged to follow strict water management rules and adopt the Cyanide Code, a global standard requiring independent audits. Still, the US representative on the IFC board raised “serious concerns” about cyanide use and the resettlement of locals.

The first reported spill came in the same month that full production began. In March 2016, cyanide and arsenic leaked from the mine. Fish floated downstream. Skin rashes were reported among locals. The company briefly paused operations but publicly downplayed the spill, saying “there has been no adverse impact on any human settlement.”

That 2016 incident was the first of four confirmed cases of pollution. The company would repeatedly violate permitted levels of cyanide discharge and the limits recommended by the Cyanide Code.

The Code is designed to protect workers, communities and ecosystems. ��“Cyanide is highly toxic to fish at extremely low concentrations,” said Eric Schwamberger, a senior official at the International Cyanide Management Institute.

In June 2020, EPA inspectors found Bea Mountain operating an unapproved wastewater system, and detected water contaminated with high levels of copper and iron. When inspectors tried to look at the company’s own testing data, Bea Mountain refused access.

“The Company refused to grant the EPA team access to its internal monitoring laboratory reports; physical access to the laboratory was also not approved,” the EPA wrote in a report at the time.

That same month, Bea Mountain withdrew from the Cyanide Code without ever undergoing a single audit, Schwamberger said. He called such withdrawals “uncommon.”

In May 2022, dead tilapia, pipefish and crawfish drifted down the Marvoe Creek, which flows into the much larger Mafa River running down to the Atlantic. Six days later, the EPA reported that a spill from Bea Mountain’s tailings had suffocated the fish “due to exposure to higher than permissible limits of free cyanide.”

The company knew about the pollution but withheld the information “from both the community and the Agency until downstream communities first started observing dead fish species,” according to the EPA report. Bea Mountain failed to alert the authorities or the public within the required 72 hours. Villagers expressed “suspicion” at two “unusual visits” made by environmental staff to the river before the company admitted to the spill, the report noted.

More than ten miles (17 kilometres) downstream in Wangekor, locals say they hauled in dead fish before any warning reached them. They believed the sudden bounty was “a gift from God,” said Philip Zodua, a representative of communities along the Mafa River.

Six residents who live downstream of the Bea Mountain facility told The Gecko Project/AP they and their families fell ill after eating fish from the river in June 2022, following the spill. “The entire town bought the fish and cooked it,” said resident Jenneh Kamara. Only later did they hear an announcement from a local journalist warning them not to eat them.

Another villager, Korto Tokpa, said she saw children collecting dead and dying fish from the river. “They were all sick; vomiting, throwing up, and going to the toilet the whole night,” after eating them, she said.

Hawa Hoff, who farms okra with her husband, said her family also suffered from vomiting and diarrhoea after eating the fish.

However, no tests were carried out on the villagers. Independent environmental scientists and toxicology experts said there is insufficient evidence to identify pollution as the cause of the reported illnesses.

Olsgard, the toxicologist, said that the community’s concerns that their health had been harmed by the spills “are real and cannot be ignored.”

“Without proper testing and transparent data, the true risks cannot be understood, and communities are left carrying all the uncertainty,” she said. “It is the company’s responsibility to fill these gaps urgently, provide clear information, and ensure people are not being exposed to preventable harm.”

Years of warnings, years of spills

2012: In an environmental impact assessment for Bea Mountain’s flagship New Liberty Gold Mine, consultancy Golder Associates warns that waste dam seepage could contaminate rivers and breach Liberia’s drinking water standards, in the absence of effective measures.2014: In an updated assessment, consultancy Digby Wells warns that cyanide and arsenic could be released into local waterways at above safe limits, if not properly treated.

2015: In a project plan for the mine, SRK Consulting cautions that arsenic could exceed WHO limits and threaten water sources and wildlife without stronger safeguards, “which may impact on the local communities drinking water”.

March 2016: Cyanide and arsenic leak from the mine. A news report says fish die downstream and villagers develop skin rashes. Bea Mountain’s parent company publicly acknowledges the cyanide release.

Late 2016: The Mapa Group (then named MNG Group) acquires Aureus Mining, parent company of Bea Mountain. Aureus Mining is renamed Avesoro Resources.

July 2018: Pollution spills from Bea Mountain’s waste dam, according to a former company worker, who says the contamination entered a nearby creek killing fish.

June 2020: Liberia’s EPA finds the company running an unapproved wastewater system. Tests show copper and iron above legal limits at discharge points around its mine. Bea Mountain refuses inspectors access to its laboratory and testing records.

June 2020: The International Cyanide Management Institute says Bea Mountain has withdrawn from the Cyanide Code without undergoing a single audit.

May 2022: The EPA finds dead fish downstream of the mine. A spill of cyanide from Bea Mountain's waste dam caused fish to suffocate, the agency reports.

May and June 2022: Villagers report finding dead and dying fish downstream of the mine. They say they fell ill after eating the fish.

February 2023: Another spill, according to the EPA. Inspectors find “a huge quantity of raw copper sulfate” leaking into the environment. Six of nine EPA water samples exceed legal limits for cyanide and copper.

When EPA inspectors arrived on the scene to test the water, days after the spill, they found arsenic and cyanide levels above legal and recommended limits and dead fish. Schwamberger said the cyanide concentrations reported by the EPA — from water flowing out of the tailings facility — were more than ten times the concentration “that would typically be considered to be lethal to fish.”

“Cyanide incidents like this are very unusual, at least from our surveys of the press around the world,” he added.

The EPA recommended a fine and ordered the company to provide bottled water and food aid for 90 days, along with a full pollution assessment. But when inspectors returned in July, residents described the company’s support as “inadequate.” Bea Mountain claimed it had delivered more than was recorded but “could not provide a list.”

Villagers “expressed weariness of the frequency of the same situation over time,” the agency noted in May 2022.

In an emailed statement, the EPA said the company had fulfilled its mandate to provide food and water.

Less than a year later, in February 2023, another spill occurred. This time, the EPA documented “a huge quantity of raw copper sulfate” leaking into the environment. Photos showed turquoise liquid flowing uncontrolled downstream. Six of nine water samples taken breached legal limits for cyanide and copper.

An EPA official involved in the investigation, speaking without authorisation and anonymously, told The Gecko Project/AP that Bea Mountain had constructed a tailings dam that was too small. When mining began, it overflowed and waste spilled into the river.

A former senior worker at Bea Mountain, speaking anonymously, said the company had originally avoided building more effective barriers so it could make “more money.” In the wet season water would overflow the banks meant to contain the waste, they said.

In response to a request to comment on the findings of this investigation, MKS PAMP, the Swiss gold trader and refiner that buys from Bea Mountain, said it “takes these matters very seriously.”

The company said it commissioned an independent assessment of the Liberian mine in early 2025, which found no basis to cut ties but identified areas for improvement related to security, health and safety. A follow-up site visit is planned for this year.

MKS PAMP said it goes “above and beyond legal requirements and industry standards” in assessing supply chain risks, but declined to share the findings of the 2025 assessment, citing confidentiality. It did not directly address questions about repeated chemical spills, permit breaches or delayed community warnings documented in this investigation.

The company told The Gecko Project it would ultimately end the relationship if Bea Mountain doesn’t improve.

While EPA inspectors have repeatedly recommended fines, only one penalty — a $99,999 fine in 2018 — was issued. Yet for reasons that were not explained, the fine was reduced to $25,000. The current EPA leadership says it is reviewing whether that payment was final.

In a written response to requests for comment, the EPA said the spills documented in its reports were “legacy challenges” that occurred before its current leadership of the agency took office in 2024. The agency acknowledged three pollution incidents between 2016 and 2023 in which laboratory tests found “higher than permissible levels of free cyanide,” and confirmed fish deaths were caused by cyanide, copper sulfate and arsenic leaking from the mine’s tailings dam.

The EPA said it ordered Bea Mountain to hire an EPA-certified third-party consultant, and reinforce the tailings facility, and that these measures “were implemented.”

“No entity is above the law,” the agency said.

While linking pollution to illness in communities is difficult in areas with scarce medical data and other potential causes, several experts said the contamination presents a clear risk to human health. Toxicologist Mandy Olsgard said the concentrations of cyanide, arsenic and nitrates in samples collected from water being discharged from the mine “were much higher than safe levels of exposure.”

But the promised safeguards may come too late for the people of Jikandor to remain safely in their homes.

Following an EPA recommendation, a legally binding agreement was reached in May 2025 to relocate and compensate Jikandor village, located downstream of the mine’s waste facility. The EPA said it is monitoring the process.

Dr Paul, the earth scientist, said the presence of copper and arsenic in the river was especially troubling because both can accumulate in aquatic ecosystems over time.

“These are communities eating the fish,” he said. “If that continues, you could start seeing problems with babies; we’re talking about impacts on an annual time scale.”

Aqueous geochemist Dr Ann Maest described the copper levels recorded by the EPA in February 2023 as “very high”. “Assuming they are accurate depictions of the site, no wonder the copper concentrations are so high,” she added after reviewing photos of the bright blue discharge. “This is very unusual — it’s an indication of a poorly run mine operation.”

She said the onus was on buyers to satisfy themselves that the mine was being operated safely. “Even if improvements were made, they’d need to see them with their own eyes — the treatment plant, the tailings facility, what’s changed. If they can’t convince themselves things have improved, they shouldn’t buy the gold.”

Read more reporting from The Gecko Project on The Politics of Deforestation & Critical Minerals.

Join The Gecko Project's mailing list to get updates whenever we publish a new investigation.

Reporting by Alon Aviram & Ed Davey

Editing by Tomasz Johnson

Fact-checking by Ed Davey & Tomasz Johnson

Header image shows Jikandor Village. By The Associated Press/Misper Apawu.